Miniature longcase clock with calendar

Clockmaker: Daniel Quare British

Clockmaker: Stephen Horseman British

Firm of Quare and Horseman British

Daniel Quare (1647/49–1724) was probably born in Somerset, England. Like Edward East (1602–1697), Ahasuerus I Fromanteel (1607–1693), and Thomas Tompion (1639–1713), he was among the most successful seventeenth-century London clockmakers; however, he was considered a “foreigner” because he was not born in London. After 1631, when the Clockmakers’ Company had obtained its charter, membership in the company was the usual method of gaining the privilege of doing business in the city. The opportunity to make and sell clocks and watches in the City of London was prohibited to those who were not members of a London company. Ordinarily, the aspiring clockmaker would serve an apprenticeship under a recognized member of the Clockmakers’ Company, but the apprenticeship was long and the number of apprentices that a clockmaker could have at one time was usually severely limited. Alternatively, an aspiring clockmaker could gain work by becoming a member of one of the other London companies, such as the Goldsmiths’ Company, where East was apprenticed, [1] or the Blacksmiths’ Company, which accepted Fromanteel in 1631.[2] Others could be admitted by right of patrimony, and others who could purchase admission to a company were allowed entry if approved by that company, but the fee was high and nearly always more than that for a London-trained apprentice. Still, another alternative was to practice the craft outside the city limits or in certain nearby areas where foreigners such as French Huguenot craftsmen had settled.

It is not known where Quare was trained, but he became a Free Brother of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1671 as a “Great Clockmaker” (turret clockmaker).[3] In January 1701, he took Stephen Horseman (died 1740) as an apprentice.[4] Horseman became Free Brother of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1709,[5] and Quare’s partner about 1718. He continued the firm after Quare’s death in 1724 and until it went bankrupt in 1729 or 1730.[6]

While noting that Quare’s Quaker religion prevented him from swearing an oath of allegiance to the English king, thus precluding an appointment as clockmaker to the king, historian Cedric Jagger outlined Quare’s professional and social success, stressing that Quare gained direct access to aristocratic circles, both in England and on the European Continent.[7] Without question, Quare was among the most remarkably skilled and inventive clockmakers who came to seventeenth-century London in order to make their reputations. One of Quare’s contributions to horology was the invention of a repeating mechanism for watches (see entry 33 in this volume). An early example, possibly the first of his watches with a quarter-repeating mechanism, is now in View of the month-going movement, showing the going train the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.[8] Clocks that went for long periods before needing to be rewound were another specialty. Quare’s longcase clock, still in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court, near London, not only indicates both solar and mean solar time but also runs for a year on a single winding.[9] Another of Quare’s year-going longcase clocks is now in the British Museum, London.[10] The month duration of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock is, thus, not so surprising, but the fact that Quare and Horseman were able to create the movement and weights to fit into so small a case makes this clock remarkable. The case, in fact, barely accommodates the movement, and the door to the trunk had to be hollowed out to provide room for the free descent of the exceptionally heavy weights required by the clock’s long duration.

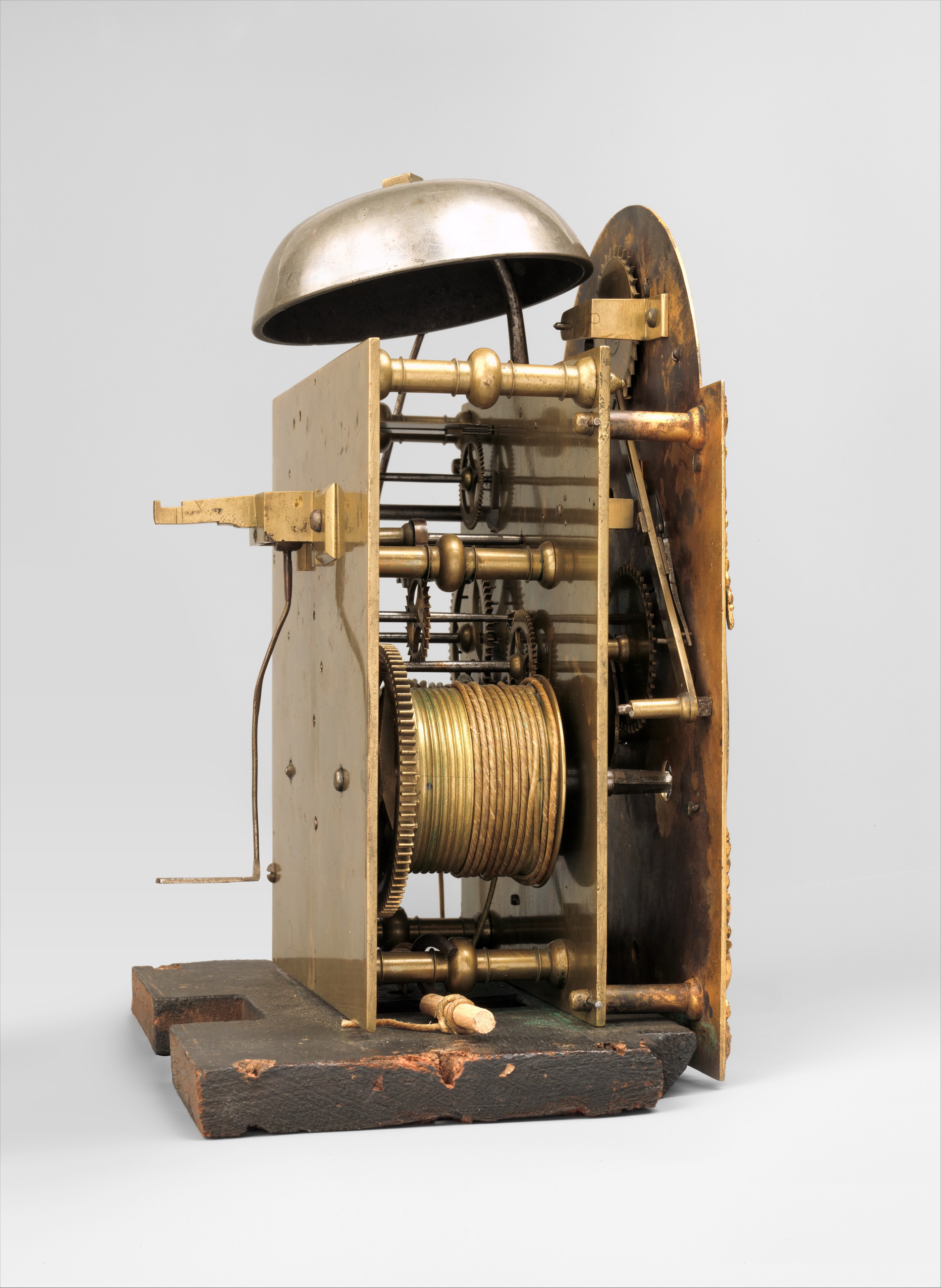

The movement consists of two rectangular brass plates held apart by five turned pillars that are pinned to the front plate. It contains a going train of five wheels and an anchor escapement regulated by a long pendulum. It actually runs for thirty-five days before needing to be rewound. The striking train has four wheels and a fly, and it strikes hours on a bell that is mounted at the top of the front plate. It has rack-and-snail striking. The positions of the going and striking trains are reversed from those in an ordinary clock of the period, and both trains wind counterclockwise.

The semicircular arched (or break-arch) dial is seven and one-quarter inches wide. In the center of the arch is a calendar with a chapter ring (5–31, by fives), and below is a silvered-brass chapter ring for the hours (I–XII), minutes (5–60, by fives), and two-and-one-half-minute intervals marked by fleurs-de-lis. A separate chapter ring for seconds (5–60, by fives) appears at the twelve o’clock position, and a label above the six o’clock position is engraved with the signature, “Danl: Quare & / Ste: Horseman / LONDON.” The spandrels of the dial are filled with applied reliefs of a helmeted mask-and-scroll design that is thought to have come into use about 1710.[11] The calendar’s chapter ring is framed by comparable scrolled reliefs, which incorporate masks in profile.

The case is a particularly felicitous version of the standard early eighteenth-century design for longcase clocks, only in reduced size. It relies on the use of richly figured walnut veneer, especially on the front of the plinth and on the door to the trunk, the latter framed by half-round molding that provides the only hint of ornament. Above the trunk, a convex molding supports the hood with a walnut-and-glass door to the dial of the clock, which is framed by applied wooden columns. These wooden elements support spandrels filled by fabric-backed fretwork, and a molded cornice with a fabric-backed fretwork frieze. An inverted bell-shaped dome completes the design. The sides repeat these motifs in less opulent fashion, but there is no additional fretwork, and the columns at the back of the hood are simply applied quarter rounds of wood.

There are serious signs of wear throughout the movement, and it has undergone extensive repair, some of it in London during the second half of the nineteenth century, as inscriptions on the interior document. The present anchor escapement does not fit the slot made to accommodate the easy removal of the original. The assembly for the pendulum suspension, too, has been replaced. The current hour hand was recently made to replace an earlier but clumsy substitute for the original steel hand. The minute hand is original but has been broken and repaired by soldering.

The fretwork on top of the hood and the right spandrel were replaced sometime before the clock entered the Museum. A number of areas of veneer had separated from the underlying oak carcass. The top of the trunk and the hood had seriously warped to the right, perhaps owing to the strain caused by the extra-heavy weight required by the striking train that furnishes power for approximately 4,881 blows in a single winding.

The clock had been in the possession of the American theatrical impresario David Belasco (1853–1931) when it was bought at auction by dealer Partridge, Inc., for Irwin Untermyer.[12]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Loomes 1981, p. 205.

[2] Ibid., p. 236.

[3] Ibid., p. 451.

[4] Jagger 1983, p. 49.

[5 ]Clockmakers’ Company, London, Court Minute Books, Ms. 2710/3, 1699–1729, p. 98r, entry of Sept. 29, 1709, Guildhall Library, London. Horseman was admitted without payment.

[6] An account of the bankruptcy of “Stephen Horseman, of Exchange Alley, London, Citizen and Clockmaker” appeared in the London Gazette (Nov. 28–Dec. 1, 1730), p. 2. An inventory of possessions for the bankruptcy of Robert Sutton, dated Jan. 1730, also indicates that Horseman was bankrupt at that time. See Robert Sutton 1732, p. 16.

[7] Jagger 1983, pp. 49–51.

[8] Inv. no. WA1947.191.85. See Thompson 2007, pp. 46–49, no. 21.

[9] Inv. no. RCIN 1040. See Jagger 1983, pp. 49–51.

[10] Inv. no. CAI-2098. See Thompson 2004, pp. 94–97.

[11] Robinson 1981, p. 450, no. 12.

[12] Anderson Galleries 1931, p. 187, no. 1233, ill.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.