Table or bracket clock with calendar

Clockmaker: Daniel Delander British

Not on view

The development of longcase clocks by English clockmakers during the last quarter of the seventeenth century by no means discouraged them from producing spring-driven table clocks in wooden cases. These table clocks had short pendulums, most had verge escapements, and they did not require as careful leveling as longcase clocks. Above all, table clocks were portable and easily moved to wherever they might be needed. Many of these clocks also had the advantage of telling time at night in an era when lighting a candle in darkness could be difficult. One invention for this purpose was the dial with revolving openwork numerals, which were illuminated from behind by a candle. The pull-repeater, however, an application of a device invented by Edward Barlow (1638–1719) in 1676, was more practical. The repeating mechanism allowed the clock to strike the previous hour on a bell when a string that was attached to the device was pulled. Quarter repeaters, which required two separate bells, permitted the striking of the quarters as well as the previous hours when the string was pulled. Several other types of hour and quarter-hour striking mechanisms can also be found in English table clocks.[1] Among the seventeenth-century English table clocks in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection is one by Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) that incorporates the more expensive string-pulled quarter-repeating mechanism in its movement (64.101.867).[2]

An account from 1710 for payment for “a shelf for my repeater”[3] explains the better-known name for these clocks: bracket clocks. These clocks could be placed on a shelf on a wall, but equally on a table or a desk. Their origin is traceable to the spring-driven, wooden-cased architectural clocks from the 1660s, but they soon began to develop a style of their own. During the course of the last quarter of the seventeenth century, domes were added to the top of their cases. Eventually, some domes were more elaborately shaped into forms that resembled bells, and sometimes they were made of openwork metal, when they were known as basket tops.[4]

About 1715, the square or rectangular dial plate began to give way to an arch or a break arch at the top of the plate, which allowed for a more comfortable accommodation of extra functions, such as calendars, dials for silencing the striking, and regulation of the pendulum. About twenty-five years earlier, a slot in the dial plate was introduced to reveal a small brass image connected to the pendulum, the motion of which it would mimic. Not only did it indicate at a glance whether the clock was running, but it also provided a way of starting the pendulum without turning the clock around.

At a little more than twenty-two inches in height, the Museum’s clock by Delander is both taller and wider than the great majority of table clocks of the last quarter of the seventeenth century. It is even larger than most of the table clocks of the early eighteenth century, ordinarily recognized as being taller than earlier examples, which were approximately one foot in height. The case of the Museum’s clock is essentially a rectangular wooden box with a framed glass door to the dial, another framed glass door in the back, and glass panels on the sides. The case rests on a molded wooden skirt and is fitted with an oak seat board inside. At the top, the clock is bordered on all four sides by a profile molding that is also veneered with matching burl walnut and supports an inverted bell top with a sturdy bail handle of brass. Two simple brass keyhole escutcheons ornament the hinged door to the dial: the escutcheon on the left is functional; the other is blind. A slot cut in the top of the door to the dial contains a delicately cut-out wooden fret backed with red silk that completes the relatively severe design of the case. The shape of the slot repeats that of one in the frame of the case that allows the sound of the bell to escape.

For all of its greater height, however, the door to the dial plate and the dial plate remain rectangular rather than arched at the top, as fashion in the new century increasingly demanded. The dial plate is of gilded brass with a matte center and a silvered-brass chapter ring for hours (I–XII), with lozenges marking the half hours, and an outer circle with minutes (5–60, by fives), each minute division marked by an engraved line, and each half-quarter hour marked by a lozenge. An aperture above the arbor for the hands displays the false pendulum, and another above the six o’clock position displays the day of the month. Above, on the left, is the hand for silencing or activating the striking train. The hand is encircled by an engraved ring of silvered brass marked “strike” and “silent.” It is balanced on the right by another ring with a similar hand (marked 5–60, by fives), this one for the so-called rise-and-fall device for adjusting the length of the clock’s pendulum. Between the two rings, the signature, “Dan Delander / LONDON” is engraved, and below are applied foliate scrolls, variants of the ornament that flanks the human masks in the spandrels below. The hour and minute hands are pierced and finely sculptured steel.

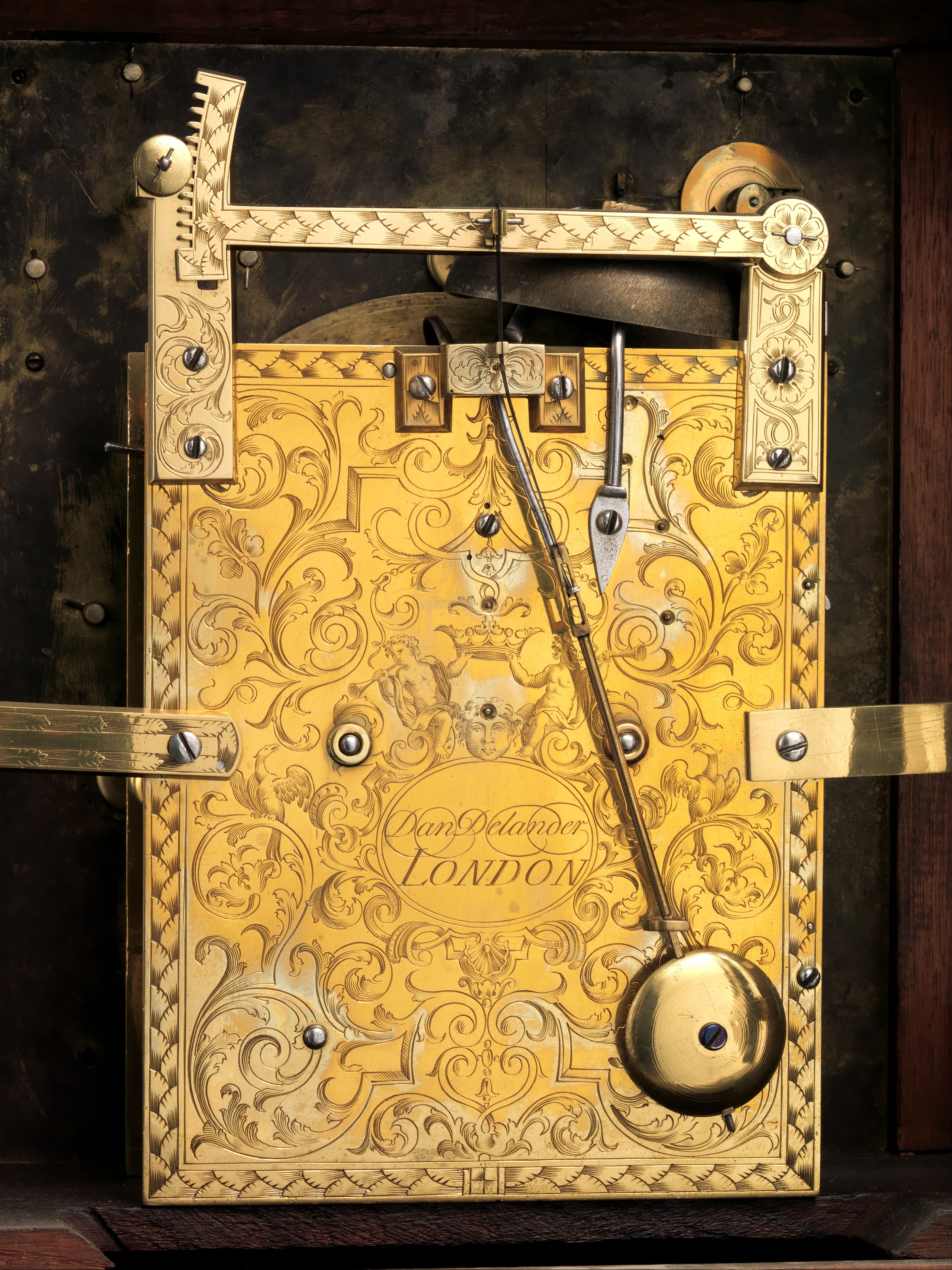

The eight-day, spring-driven movement consists of two rectangular brass plates, which are held apart by five turned pillars; a going train of three wheels; and a horizontal verge escapement controlled by a pendulum approximately nine and one-half inches long with spring suspension and a circular brass bob. Its length can be adjusted by moving the brass bar mounted at the top of the back plate. The striking train consists of four wheels and a fly. The hours, controlled by a rack-and-snail mechanism, are struck on a single bell mounted on the back plate. The clock was not provided with a repeating mechanism, although the “strike-silent” feature would have allowed convenient use of the clock in a bedroom, where unrestricted striking of the night hours would be an annoyance at the very least.

The back plate, visible through the glass door at the back of the clock, is a riot of engraved decoration that is typical until far into the eighteenth century. A cartouche placed a little below the midpoint of the plate displays the engraved signature, “Dan Delander / LONDON.” Above the cartouche is the head of an infant and a coronet held aloft by two trumpet-blowing genies who are surrounded by leafy scrolls upon which two birds are perched. The edges of the plate are engraved with a trellis-like pattern that repeats on the surface of the rise-and-fall bar for the adjustment of the pendulum. The pattern appears again on the left bar for securing the movement to the case that is screwed at one end to the back plate and at the other end to the side of the case. The bar at the right is undecorated.

The right bar is undoubtedly a well-made replacement. The dial foot at the five o’clock position is broken near its end, and the escape wheel has been replaced. On the case, a piece of veneer is missing on the lower left side, and the end of the fretwork design at the right is a replacement. The veneer has undergone some shrinkage and cracking but retains its rich coloring that softens the severity of the design of the case.

The donor, Irwin Untermyer, acquired the clock in 1971 in London, where it was described as the “property of a lady of title.”[5] Nothing further is known of its provenance.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] These have been described in greater detail in Allix 1993.

[2] Acc. no. 64.101.867.

[3] Quoted in Barder 1993, p. 18.

[4] For the progression of styles, see Cescinsky and M. R. Webster 1969, pp. 249–58; Barder 1993, pp. 24–72.

[5] Christie’s 1971, p. 14, no. 18, ill.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.