Siren

possibly commissioned by the Colonna

Confidently modeled and roughly cast, our bronze possesses a visual allure consonant with its subject’s storied song. The figure’s youthful physique, parted lips, and confident manipulation of her tails communicate the vivacity and disconcerting hybridity of the mythological subject. Smooth skin, ribbed fins, patterned scales, and especially the flicker of massed hair over the shoulders and down the back reveal an artist adept at arranging sculptural forms and manipulating the play of light across volume and a variety of surfaces. With the shock of familiar anatomies—human and piscine—in unexpected union, and with all the resplendence of large-scale, metal, light-reflecting sculpture, the Siren undoubtedly continues to fulfill much of its original promise in spite of the effects of time.[1]

At the time of its acquisition in 2000, Olga Raggio dated the bronze circa 1570–90 and suggested Taddeo Landini as a possible author. Ian Wardropper accepted that dating, while the present author also entertained the possibility that it was made in the early seventeenth century, and both authors expanded the list of modelers and casters in Sistine Rome under consideration.[2] In a more recent study of Camillo Mariani’s Roman period, Fernando Loffredo convincingly attributed our bronze to that Vicentine sculptor, circa 1600. His strongest argument is stylistic, soundly based on the Siren’s formal relationship to Mariani’s large stucco statues of saints for the rotunda of San Bernardo alle Terme (1598–1602).[3] He also pointed out that Mariani was praised during his Roman years for his ability in casting bronze, a skill already demonstrated before his arrival in Rome, in the Mother Ape group (cat. 111).[4]

It has yet to be determined when our bronze came into the Rothschild collection at the Château de Pregny, built by Adolphe de Rothschild in 1858 and remaining in that family. In an earlier publication, the present author collocated published inventories and a drawing to trace details of the sculpture’s earlier history as follows. In Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte’s posthumous inventory of 1627, the bronze was in his palace on via di Ripetta, Rome, in a room that, at least for the purposes of the notarial inventory, was called the Stantia or Sala della Sirena. By 1644, it was in the Palazzo Barberini alle Quattro Fontane and the possession of Cardinal Antonio Barberini, in a room near the Sala Ovale at the heart of the piano nobile of the palace. In both of these circumstances, the Siren was installed with a strigilated marble sarcophagus, which can be identified with one that remains at the Palazzo Barberini (fig. 110a). The sculpture appears next in the other main Barberini residence in Rome, the Palazzo ai Giubbonari, where it is listed in Cardinal Antonio’s posthumous inventory of 1671. The third mention of the Siren in a Barberini inventory comes around 1680 in a list of Antonio’s nephew Maffeo’s possessions, by which time it had returned to the Palazzo alle Quattro Fontane. The sculpture likely remained at that palace, as it was there in the 1720s that Giovanni Domenico Campiglia noted it in a list of sculptures he sent to his patron, Richard Topham in England, who in turn ordered a drawing of it (fig. 110b).[5]

Campiglia’s drawing provides the strongest evidence that our bronze is the same as that once owned by the Barberini and Cardinal del Monte. The left fin, missing in Campiglia’s drawing, is of different facture and alloy than the body, apparently a repair made subsequent to the drawing. Comparison of the drawn and sculpted crown, along with its misalliance with the bronze figure’s head, suggests that what we see today is a replacement, but one made perhaps in consultation with the original.[6]

The crowned, frontally disposed piscine siren grasping her tails was a heraldic symbol of several branches of the powerful Colonna family.[7] Naturally, attempts have been made to associate The Met’s bronze with that family’s patronage. Raggio proposed that it was made for the Palazzo Colonna in Rome, and Wardropper suggested a connection to the naval victory of Marcantonio Colonna at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.[8] As with his attribution, Loffredo has offered the most specific suggestion for patronage to date, namely that it was made for a fountain in the garden of Cardinal Ascanio Colonna in Marino. That fountain is known through archival documents pertaining to its construction in 1598 and its relocation the following year, and a drawing that can be dated between 1598 and 1609.[9]

While it is certainly a possibility, and an intriguing one, Loffredo’s arguments against this hypothesis seem more convincing than those for it.[10] To the former should be added the drawing’s purported rendering of our Siren with the same ink and washes as the two other sirens on the fountain, which it is proposed were made of stone (while the artist distinguished the fountain’s architectural elements and the water with different colors); the careful arrangement of the sirens’ hair in braids rather than the loose tresses of our bronze; and above all the looped tails present in the drawing, which are more typical of Colonna imagery than the simpler recurves described by those elements in the bronze.

Given our inability at this point to substantiate a connection to the Colonna family, it might be worthwhile to use Ockham’s razor to open the possibility that the Siren was made for Cardinal del Monte, in whose collection we first learn of it. The cardinal’s deep interest in music theory and his patronage of musicians and composers have been well documented and reconstructed.[11] He also moved in a sector of Roman society that included Cesare Ripa, Torquato Tasso, and Giambattista Marino, each of whose literary efforts often invoked hybrid allegories and other marvels.[12] It is tempting to think of our Siren as a cousin of the speaking likenesses that populate Caravaggio’s paintings of musician youths made for del Monte,[13] but with the added hermetic depth of an emblem or an embodied riddle that would have stimulated the members of intellectual societies such as the academies of the Insensati or the Unisoni active in Rome around 1600.[14]

Her coarse tumult of hair makes it clear that the Siren was meant to be seen from both front and back. Nonetheless, it is a notably planar composition. Mariani or any other artist working at this level would have been able to generate a serpentine composition if directed, and may well have relished curling or entwining the tails, if doing so did not conflict with other requirements of the design. The design decisions reached in the Siren could indicate that the marble sarcophagus, which also has two main viewpoints, was kept in mind from the time of the bronze’s commission.[15] That may help explain why the two objects remained closely associated for decades through different collections.

-PJB

Footnotes

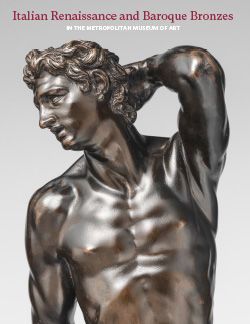

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. The bronze was well cast in one piece with the exception of the crown, which does not appear to be original. The surface has been filed in some areas, apparently to remove corrosion pitting. R. Stone/TR, December 22, 1999.

2. Wardropper 2011, p. 92; Bell 2011, p. 161.

3. Loffredo 2016, pp. 198–99.

4. Ibid., p. 196.

5. For a more detailed discussion of the Siren’s ownership, see Bell 2011, pp. 161–66.

6. Ibid., p. 166. See also note 1 above.

7. Wardropper 2011, p. 90, references examples pertaining to the Paliano and Palestrina branches.

8. MMA 2000, p. 24; Wardropper 2011, p. 92.

9. Loffredo 2016, pp. 200, 206 n. 47, 207 n. 49.

10. Ibid., p. 201.

11. For example, Camiz 1991; Whitfield 2008; Waźbiński 1994, vol. 1, pp. 99–103.

12. Whitfield 2008, p. 4.

13. See Camiz 1991.

14. See Whitfield 2008.

15. Pace Loffredo 2016, p. 199.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.