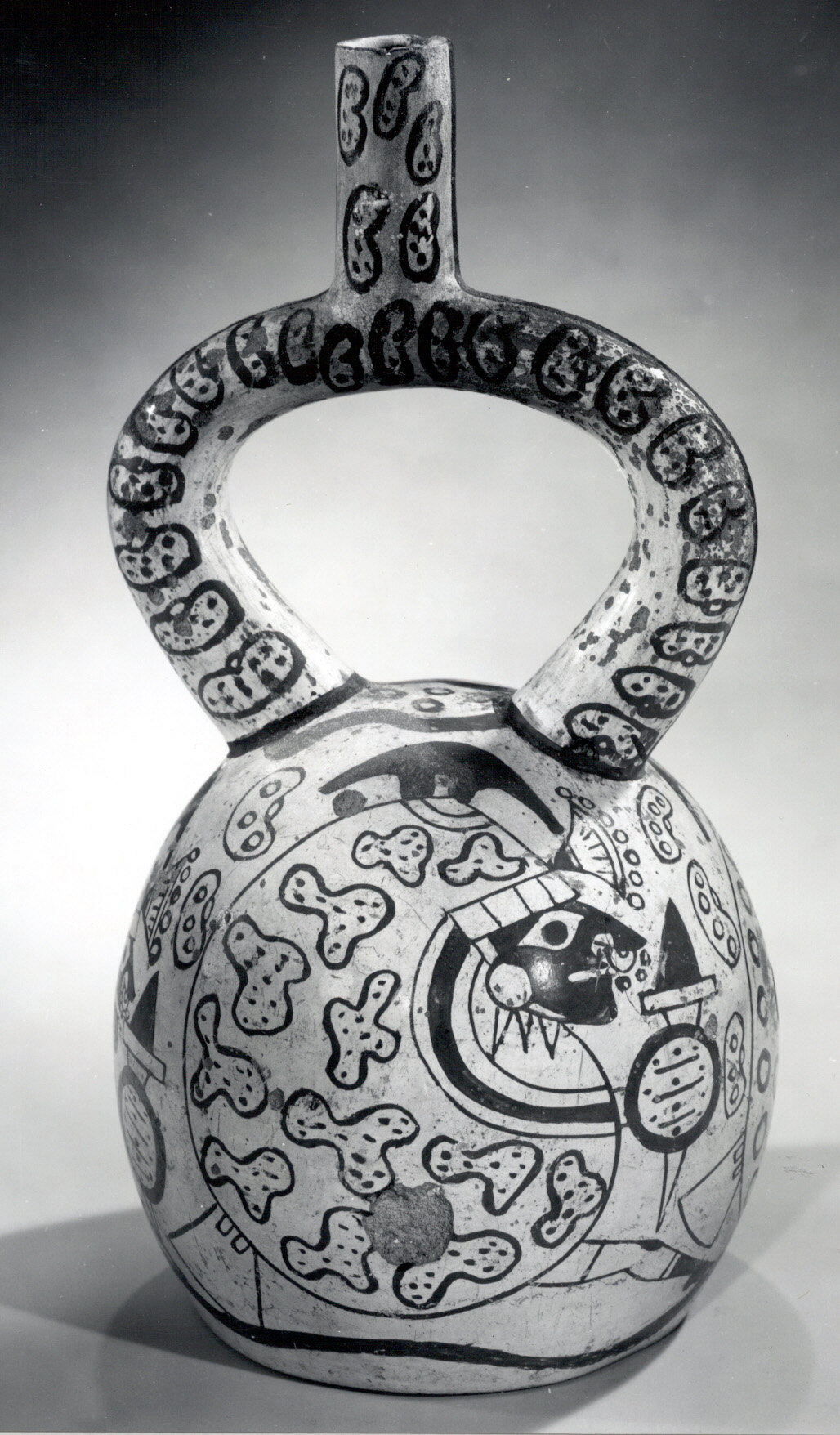

Stirrup-spout bottle with bean warriors

Not on view

Fineline, a style characterized by detailed figures and scenes delicately painted in a reddish slip (a suspension of clay and/or other colorants in water) on a cream background, became popular with Moche artists on Peru’s North Coast after 500 CE. This technique allowed painters to depict complex scenes inspired by rituals and mythological stories. Humans can be shown as protagonists, engaged in combat or hunting, but these vessels also feature enigmatic beings such as beans dressed in full battle regalia.

The four bean warriors painted on this bottle’s chamber have bodies in the shape of a bean, complete with designs suggesting the mottling seen on lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus). The face is rendered at the hilum of the bean, where it would have been attached to the plant’s stalk during development. Each warrior wears a headdress that ties under the chin and is surmounted by a crescent-shaped ornament. Another ornament projects forward, above the face, and likely represents an array of feathers. The bean warriors also wear a nose ornament, ear spools, and carry a shield and a mace. The bean warriors’ regalia is completed by tiny backflaps, a type of body armor that is normally suspended from the waist at the back of the wearer. A single, elegant leg, adorned with body paint, extends forward from each bean, indicating its swift movement. Beneath them a thin red line indicates an uneven and arid terrain. The artist added additional (not obviously animated) beans between and above the figures and along the vessel’s spout.

The stirrup-spout vessel—the shape of the spout recalls the stirrup on a horse's saddle—was a much-favored form on Peru's northern coast for about 2,500 years. Although the importance and symbolism of this distinctive shape is still puzzling to scholars, it has been suggested that the double-branch, single-spout configuration may have prevented evaporation of liquids, and/or that it was convenient for carrying. Early in the first millennium CE, the Moche elaborated stirrup-spout bottles into sculptural shapes depicting a wide range of subjects, including human figures, animals, and plants worked with a great deal of naturalism. About 500 years later, bottle chambers became predominantly globular, as in the present example, providing large surfaces for painting complex, multi-figure scenes.

The Moche culture (also known as the Mochica) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200-850 CE, centuries before the rise of the Incas (Castillo 2017). Over the course of some six centuries, Moche communities built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although it is not known with certainty whether the Moche formed a single centralized state, the centers clearly shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010). In the early twentieth century, a vessel related to the present example was excavated at Huaca de la Luna, an important site in the Moche Valley, by the archaeologist Max Uhle (Grave 9, Moche Site F) Another vessel with bean warriors, depicted in a more proliferous composition, is now in the Art Institute of Chicago (accession number 1955.2274; Saunders and O’Neil, 2024:155, plate 22).

Several varieties of beans were cultivated early in Peruvian prehistory (c. 2,000 BCE), and beans are often depicted in Moche art, as well as in the art of their neighbors to the south, the Nasca (see Ryser, 2008, for a comprehensive exploration of the subject). In the modern world, beans are often thought of as having uniform coloration, but the original cultivars had a variety of colors and were often mottled. Beans, along with maize, were important crops in the coastal Andean region, and thus their frequent representation may relate to the importance of successful growing seasons. But other associations may also be considered. For example, beans may have been thought to have special properties for divination, and the frequent representation of individuals carrying small bags may relate to the transport of beans (Sawyer, 1966). The animation of beans, however, such as in the present example where the legume is anthropomorphized and weaponized, requires further consideration. Raw beans can be toxic, but they are also generative and may have been seen as seeds multiplying warriors. Other properties, such as the predator avoidance behavior of the lima bean plant itself, may have been noticed and considered significant. Lima bean plants can thwart attacks by herbivorous spider mites by attracting the predator of the lima bean’s predator, carnivorous mites. Tiny but mighty, beans may have been visual metaphors for a warrior’s cunning and prowess.

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator, Arts of the Ancient Americas, 2024

Published

Wassermann-San Blás, Bruno John. Céramicas del antiguo Perú de la colección Wassermann-San Blás. Buenos Aires: Bruno John Wassermann-San Blás, 1938, no. 62, p. 40.

Sawyer, Alan Reed. Ancient Peruvian Ceramics: The Nathan Cummings Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966, no. 67, p. 50.

Pillsbury, Joanne. “Violent Legumes.” In Picture Worlds: Storytelling on Greek, Moche, and Maya Pottery, edited by David Saunders and Megan E. O’Neil. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2024, pp. 122-123.

References and Further Reading:

Castillo, Luis Jaime. “Masters of the Universe: Moche Artists and Their Patrons.” In Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017, pp. 24-31.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion.” In New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010.

Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland. Moche Fineline Painting, Its Evolution and Its Artists. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, 1999.

Quilter, Jeffrey. “The Moche Revolt of the Objects.” Latin American Antiquity 1, no. 1 (1990): 42–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/971709.

Ryser, Gail. “Moche Bean Warriors and the Paleobotanic Record: Why Privilege Beans?” In Arqueología Mochica: Nuevos Enfoques, edited by Luis Jaime Castillo et al. Lima: Institut français d’études andines and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Fondo Editorial, 2008, pp. 397-409.

Saunders, David and Megan E. O’Neil, editors. Picture Worlds: Storytelling on Greek, Moche, and Maya Pottery. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2024.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.