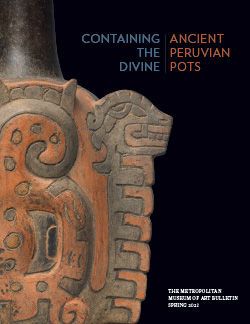

Tuber-inspired stirrup-spout bottle

Moche potters are renowned for their realistic representations of animals, plants and portraits, as well as detailed illustration of activities, such as hunting, warfare, and ceremonies. A few Moche ceramics blur the distinction between the real and the imagined in the natural world and may have represented a continuity between animal and plant species. Sometimes inspiration for these works came from eccentrically shaped stones or tubers, in which people would see other forms. Potters crafted vessel bodies that are simultaneously human, animal, and plant, such as a manioc with a human-like head and limbs positioned to evoke the movement of an insect or crustacean (see, for example, MMA 64.228.57).

This ceramic bottle combines the images of a contorted fanged human face, wrinkled on its right side, an owl, and possibly an anthropomorphized snail, all seeming to emerge from a bulbous vegetable shape. While these creatures are often depicted separately in Moche art, the reasons for their combination here are unknown.

This vessel shape is a variant on a common type known as a stirrup-spout bottle—the shape of the spout recalls the stirrup on a horse's saddle—and it was a much-favored form on Peru's northern coast for about 2,500 years. Although the importance and symbolism of this distinctive shape remains puzzling to scholars, it has been suggested that the double-branch/single-spout configuration may have prevented evaporation of liquids, and/or that it was convenient for carrying. Early in the first millennium CE, the Moche elaborated stirrup-spout bottles into sculptural shapes depicting a wide range of subjects, including human figures, animals, and plants worked with a great deal of naturalism. About 500 years later, bottle chambers became predominantly globular providing large surfaces for painting complex multi-figure scenes.

The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200-850 CE, centuries before the rise of the Inca. Over the course of some seven centuries the Moche built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although it is not known if the Moche ever formed a single centralized political entity such as a state, it is clear they shared certain unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010).

References and Further Reading

Donnan, Christopher B. Moche Art of Peru: Pre-Columbian Symbolic Communication. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, 1978.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion.” In New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo, pp. 47-69. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010.

Trever, Lisa. "A Moche Riddle in Clay: Object Knowledge and Art Work in Ancient Peru." The Art Bulletin 101, no. 4 (2019), pp.18-38.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.