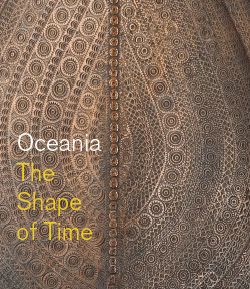

Kora ulu (canoe prow board)

This canoe prow board (kora ulu) from the Tanimbar archipelago in Maluku Tenggara (Moluccas Islands) would have been tied onto the prow of a large canoe made for long-distance voyages. Canoes were widely used in the region for daily activities and for longer trips involving trade, warfare, and renewing alliances. This kora ulu demonstrates the masterful latticework and curving forms that characterize Maluku Tenggara carvings. The interlocking single and double S-shapes (kilun etal and kilun ila’a) have been described as rolling waves crashing to either side as the canoe moves swiftly through the water. The animal depicted at the base is a fierce sea creature with large teeth lining its open mouth, poised to devour its prey. On other kora ulu that survive in museum collections today, the base includes animals associated with predatory behavior such as sharks and roosters. The latter are especially potent symbols on Tanimbar canoes not only because they are fierce animals that attack when provoked, but they also put on an impressive display of plumage just as a nobleman might show off his wealth through colorful textiles and shining jewelry. The fierce, dangerous, elite, and swift-moving qualities conveyed in the prow’s carving are the defining traits required for a successful voyage.

The motifs on the prow board indicating swiftness and ferocity – for instance the fanged sea creature amidst crashing waves depicted on this example – were reinforced by the application of powerful substances considered to be "hot." Heat and coolness were additional metaphors that structured social and religious relationships in Tanimbar; an alliance cooled off over time, loosing its force and vitality, while the renewal of that alliance made it hot once again. Ritually prepared "hot" substances applied to the canoe were considered so powerful that the water surrounding the vessel would boil, and the bow would send out waves (laluan) of turbulent winds, thunder, and lightning storms.

More than a utilitarian object, Tanimbar canoes were replete with symbolism and had agency as living vessels. The long beam that formed the base of the hull was customarily made of the bottom half of a tree trunk, which grounds the tree’s roots into the earth. Similarly, the canoe grounds a community to its origins, tracing back to ancestral voyagers who first settled the village. Before the Dutch colonial government forcibly relocated Tanimbar villages, spatial organization in each community followed the logic of a canoe. The main support beam for a house was considered the long beam of a hull, while the gable finials were referred to as kora (canoe prow boards). The stone platform in the center of each village was also a canoe – some even feature a large kora ulu made of stone. Ritual activity, ceremonial dances, and diplomatic events took place in and around these central canoes which were configured as a way to organize space at the heart of the village. Women stood in a circle in the shape of a hull and drummers formed the sails, filling the space with wind created from the drumbeats. Village leaders sat in designated positions at the center of the group, orienting the boat and its passengers on course.

The canoe is thus a metaphor for the entire community and provides a focal point for individuals to connecting to their forebears, the ancestors who originally settled the land. When descendants embarked on a voyage to renew an alliance with another village, they would sail under the name of that original canoe, embodying those ancestors and bringing the past into the present. This accounts for the fact that the rooster is a common symbol on kora ulu, for it too signals a temporal transition when a new day comes into being. The blurring of past and present meant that an alliance had not yet been formed, therefore a canoe was prepared as if going to war, recreating the original encounter between the ancestors.

#1726. Canoe Prow Board (Kora Ulu)

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.