The Artist: Quinten Massys (also known as Metsys and Matsys) was born in Leuven, the son of Catherine van Kincken and the blacksmith Joos Massys, from whom he may have received his early training. By 1491 he had launched his painting career when he entered the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a Master, thereafter taking on apprentices in 1495, 1501, 1504, and 1510. In 1509, Quinten married Katline Heyns. They had ten children, two of whom—Jan (ca. 1509–73; see

32.100.52) and Cornelis (1510/11–1556/7)—also became masters in the Antwerp Guild. The family became embroiled in the religious controversies of the Reformation,[1] and Jan and Cornelis, who were associated with a libertine sect, called the Loists, were charged with heresy and banished from Brabant, their property confiscated.

Massys’s early works exhibit knowledge of Dieric Bouts’s workshop in Leuven, the city where Massys was born and raised, but also the achievements of other predecessors, namely Hugo van der Goes in Ghent, Hans Memling in Bruges, and Rogier van der Weyden in Brussels. Among his earliest dated works is the

Holy Kindship (or the

Saint Anne Altarpiece) of 1509 (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels) painted for the Confraternity of Saint Anne at Saint Peter’s in Leuven. Soon thereafter came his initial achievements in portraiture:

Portrait of an Old Man of 1513 (Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris) and the

Banker and His Wife of 1514 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Other dated paintings that provide the linchpins for Massys’s late oeuvre are The Met’s

Adoration of the Magi of 1526, and the

Virgin and Child (Musée du Louvre, Paris) and the

Christ as Savior, both of 1529 (Museo del Prado, Madrid). In addition to these is a group of reliably documented works: the

Lamentation Triptych, commissioned in 1508 for the chapel of the Joiners’ Guild in the Collegiate Church of Our Lady (today the Cathedral) in Antwerp, and the

Portraits of Erasmus and Pieter Gillis (Royal Collection, Hampton Court, and Earl of Radnor, Longford Castle) painted in 1517 for Sir Thomas More. The

Temptation of Saint Anthony of about 1520–24 (Museo del Prado, Madrid) is signed by Patinir, but documents in an El Escorial inventory indicate that the figures were painted “by the hand of Master Quinten.”[2]

Massys’s lasting legacy as the “founder” of the Antwerp school of painting is justifiable. He was keenly aware of both the achievements of his forerunners of Early Netherlandish painting as well as of contemporary developments. The

Holy Kindship Altarpiece of 1509 (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels) and the

Saint John Triptych (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp,) likely completed in 1511 show Quinten’s clever conflation of compositional sources from Rogier van der Weyden, prints by Albrecht Dürer, and caricature studies of Leonardo da Vinci. Massys ascended to fame when that city was emerging as the economic hub of Western Europe and a center of multi-national influences. For him, in particular this meant the influx of Italian art, notably that of Leonardo da Vinci, mainly through prints. Fashionable decorative motifs for multipurpose use were also easily conveyed through the print medium and abundantly available as Antwerp was the leading European center for printmaking.[3] It was also the age of the emergence of landscape painting as an independent genre. Massys recognized that by allying himself with Antwerp’s leading landscape artist, Joachim Patinir (see

36.14a–c), he could guarantee further success for his paintings—artistically and economically—by collaborating with him. The younger Antwerp painter, Joos van Cleve (see

32.100.57), and Massys appear to have influenced each other over time and probably competed for the same clientele. The extant paintings of both artists reflect the taste of the times in an affluent period for Antwerp when secular subjects were beginning to emerge as equal in importance to religious themes.

Quinten was well-connected with the Humanists of his day. He knew Peter Gillis, who himself was close to both Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. When Dürer visited The Netherlands in 1520–21, he spent time in Antwerp and especially requested to see Massys’s house there. Dürer’s diary of his trip makes no mention of having actually met Massys. However, he did spend time with Joachim Patinir, whom he called the “good landscape painter” and who was a collaborator of Massys.

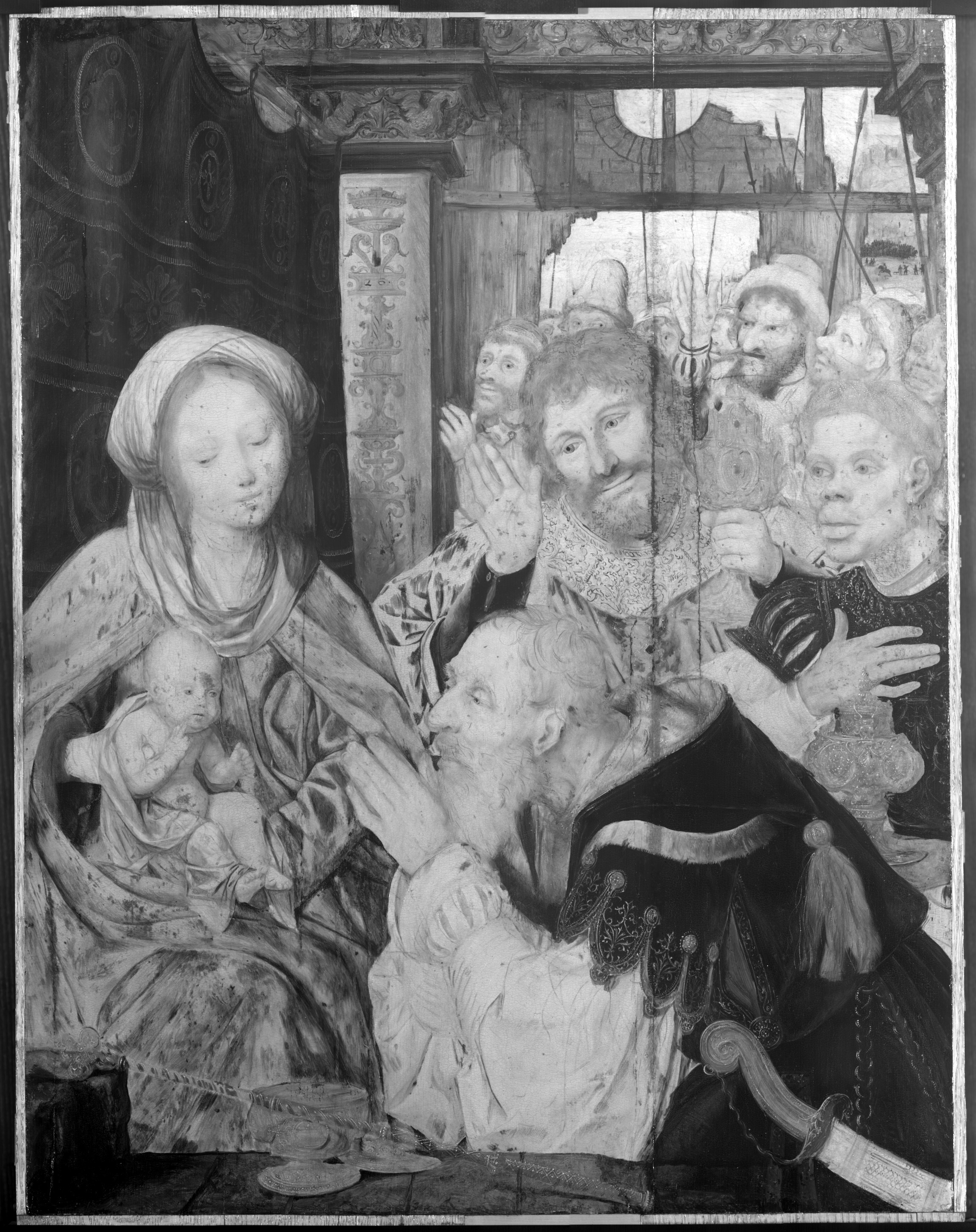

The Subject of the Painting and its Context in Early Sixteenth-Century Antwerp: The theme of the Adoration of the Magi (or Adoration of the Kings) is based on the biblical text of the Gospel of Saint Matthew 2:1–22. The verse depicted most often, and indeed the one represented here, is Mathew 2:11, wherein the three magi arrive at the dilapidated palace of the Old Testament King David, ancestor of Christ, to find the Virgin and Child, who are seated before a patterned velvet curtain, their makeshift cloth of honor. The magi press in close to the Child, paying homage to him and offering gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

The earliest representations of this much-beloved story are from the fourth century. By the fifteenth century in northern Europe, the Magi are shown as representatives of the three recognized regions of the world—usually Asia, Africa, and Europe, but sometimes also Arabia, Persia, and India—and the three ages of humans. They are often identified as Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, but which king goes with which name and with which gift varies. Sometimes, but not here, there are distinctive labels that clarify the names of the kings. The oldest king is shown in exoticized garb, including his gold-tasseled hood and the decorative falchion mounted on a thick gold chain at his waist. The middle-aged king wears a delicately wrought golden collar with jeweled pendant. The young Black king is elaborately attired in a gold-embellished tunic with

couleur changeant sleeves beneath, his hair tucked up in a dazzling woven gold snood. The magi’s gifts to the Christ Child are presented in lavish containers of intricate goldsmith work with precious stones. In the far distance at the upper right, the three magi can be seen advancing, accompanied by their retinue.

This painting is a particularly

au courant reflection of the Mannerist style of painting that predominated in Antwerp in the 1520s. Characteristic of this mode are fantastic architectural settings, an emphasis on ornament and luxury products, and highly exaggerated figure types, amplified here by the dramatic close-up of the composition.[4] Most of all, it is the subject itself that was synonymous with Antwerp at the time, as it mirrored life in that city. By the early sixteenth century, Antwerp had eclipsed Bruges as the economic hub of Western Europe and a center of international trade. As representatives of the three continents of Europe—Asia, Africa, and Europe—the three magi exemplified travelers who transported luxury goods, and the trio became the “patrons and protectors of travelers, of merchants, and of innkeepers.”[5] The Met’s painting is a reflection of Antwerp’s import trade that was “predominantly a luxury market, its high-end commodities consisting of items such as spices, sugar, silver, silk, diamonds, artworks, books and tapestries.”[6] The identification of Antwerp and its international merchants with the magi was manifest in those who adopted the name of one of the magi as their first name and, likewise, named their male children Balthasar, Caspar, or Melchior with the expectation that they would carry on the merchant or shipping profession of the family.[7] This conflation of religious and professional life explains why paintings of the Adoration of the Magi were second only to those of the Virgin (patroness of Antwerp) in the inventories of households,[8] and why there remain today such an overabundance of paintings of this particular theme.

Prominently represented here are the varied and exaggerated physiognomies of the three kings and their retinue. In addition to the kneeling old king, several of the faces of the men in the background recall the caricature studies of Leonardo da Vinci, which were probably circulating as prints in Antwerp. In addition, there is the sensitive, individualized treatment of the Black king. This, as well as another Black attendant directly behind him, signals the growing presence of sub-Saharan Africans in Antwerp. Among the largest of the group of merchants in the city were the Portuguese, who had had great success in their travel around the cape of Africa and on to points east. Although in Flanders, and later on in the Spanish Netherlands, slavery was not legal, it was tolerated.[9] In Antwerp, most of the enslaved Africans were the property of resident Portuguese merchants. Interest in and curiosity about the influx of these new residents was famously documented by Albrecht Dürer on his 1521–22 trip to the Netherlands. An entry in Dürer’s diary of March or early April of 1521 discusses drawings he made while in the company of his host, the new Portuguese factor in Antwerp, Rodrigo Fernandez d’Almada: “I drew with the metal-point a portrait of his Moorish servant, and one of Rodrigo with the pencil in black and white on a large piece of paper.”[10] The former is the sympathetically rendered

Portrait of Katharina, inscribed “Katharina 20 years old” (see fig. 1 above).

This interest shown by Dürer in Black Africans encountered in Antwerp’s daily life is evident in numerous paintings of the Adoration of the Magi made in Antwerp at the time. In addition to the painting under discussion here, and originating from the last two decades of the fifteenth century is The Met’s dramatic close-up version of Hugo van der Goes’s

Monteforte Altarpiece (Berlin, SMPK, Gemäldegalerie) of around 1470 (see

71.100).[11] Likewise, there is an

Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1515, Princeton University Art Museum; fig. 2), also influenced by Hugo, but closer to the style of Gerard David, who established a workshop in Antwerp in 1515 in order to be able to sell paintings there. This example is noteworthy for its sensitive portrayals of two Africans, both the Black king and his attendant, which, like the Black king in the Massys

Adoration, appear to be closely studied portraits, while the other male figures in the painting are generic types.[12]

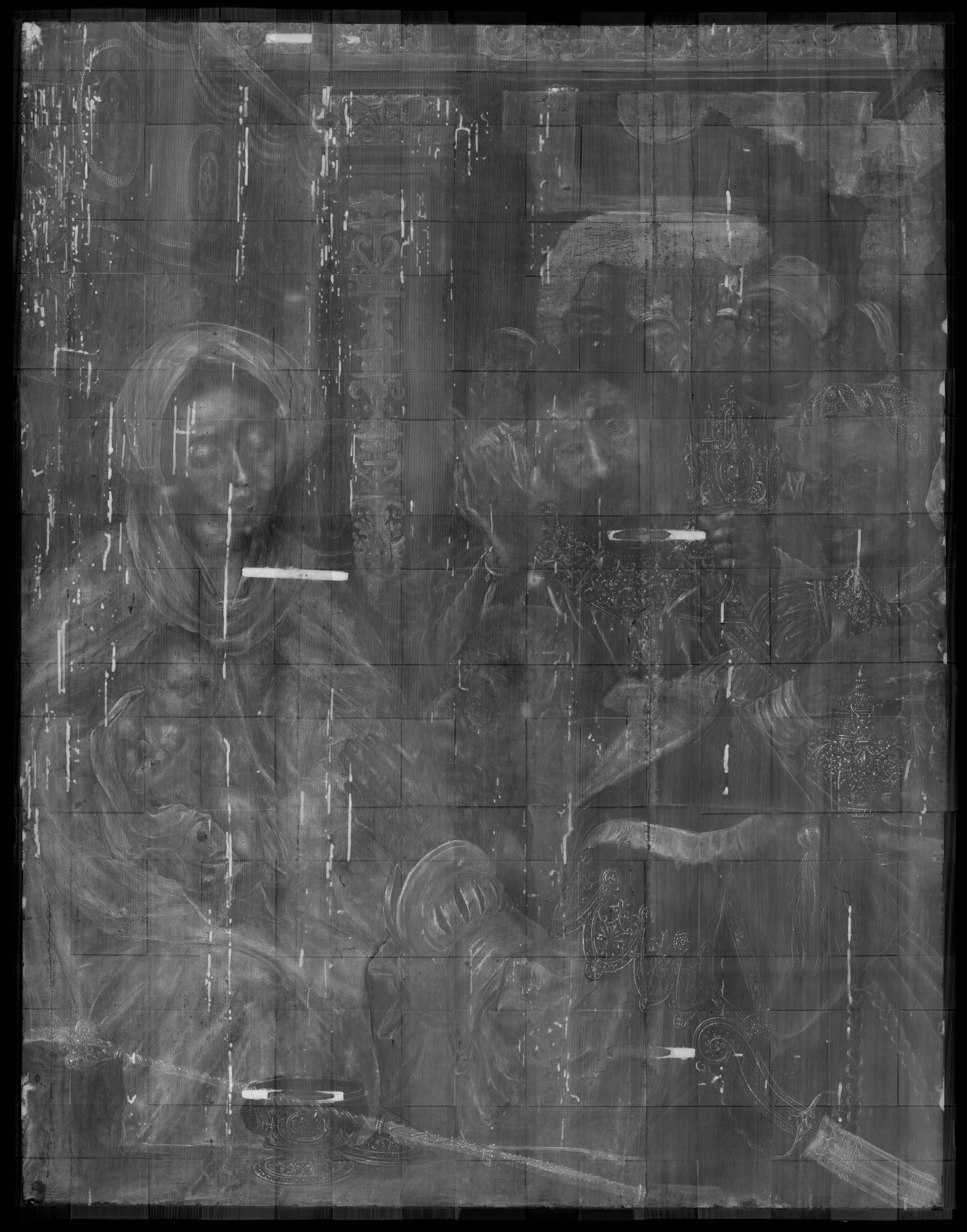

The Attribution and Date: Since Max J. Friedländer (1900) accepted the attribution of the

Adoration of the Magi to Quinten Massys, there has been general agreement, except for the occasional dissenting voice that considered it a copy after a lost composition by the artist (Baldass 1933). Massys’s composition ultimately derives from Hugo van der Goes’s influential

Monteforte Altarpiece (SMPK, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) of about 1470. But closer at hand for Massys were a series of close-up versions of the

Monteforte Altarpiece, or copies after a lost adaptation of it by Hugo himself, produced in Antwerp toward the end of the fifteenth century. The Met’s

Adoration of the Magi (

71.100) and another nearly identical version (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen) exemplify the popularity of these paintings produced in series for open market sale.

Although most scholars accept the inscription “26” on the pilaster as the date of the painting’s creation, a few related it instead to the period around 1510, when Massys first started to incorporate Leonardesque types in his

Entombment (

Saint John Altarpiece, 1508–11, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp; Völker 1968).[13] Here Massys referred to a Leonardo drawing (Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 912495) that provided the source for two of the heads of Saint John’s tormentors on the right wing. Massys probably had a copy of this drawing at hand because he referred to the far left figure in it for a member of the magi’s retinue, that is, the head (in reverse) between the middle-aged king and the Black king in The Met’s painting. Lorne Campbell has pointed out that Massys’s adaptations of Leonardesque caricatures is not limited to his earliest works, but continue to appear throughout his oeuvre.[14] As the

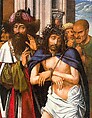

Adoration and other Massys’s works of this period, such as the

Ecce Homo (Museo del Prado, Madrid, and Palazzo Ducale, Venice, figs. 3, 4) that incorporate Leonardesque grotesque heads confirm, Leonardo’s caricatures were not directly copied by Massys, but rather adapted from his designs, as Campbell calls them, into “hybrid inventions.”[15] Another aspect of Leonardo’s art that Massys assimilated—and that is so well portrayed by the juxtaposition of the beautiful Virgin with the grizzled old, kneeling king in the

Adoration of the Magi— is what Michael Kwakkelstein described so well: “Leonardo derived great pleasure in the visual effect produced by the contrast between old and young, and between an ugly and a beautiful face.”[16]

In his late period, Massys favored depicting his figures at half-length in compositions of the Pietà, Ecce Homo, and Adoration of the Magi (Silver 1984, p. 223).The dramatic close-up of Massys’s late paintings, such as the

Adoration and the Venice

Ecce Homo, eschews a carefully constructed perspective space, instead portraying an unsettling sense of cacophony and disorder. This effect is enhanced by ornate Italianate grotesques—full and fragmentary—incorporated within the architectural decoration.[17] Only the stone ledge barrier in the extreme foreground keeps the figures from spilling out into our space, thus directly engaging the viewer as a participant in the decision to follow Christ. “…Contemplation and ethical choice” as well as a call for inner piety were imbedded in Erasmus’s

Colloques of the 1520s and other writings that emphasized spiritual betterment and righteous living.[18] As such, Massys’s

Adoration of the Magi was a visual manifestation of Erasmus’s teachings.

Maryan W. Ainsworth 2020

[1] Lorne Campbell proposed that Quinten Massys may have been the “Master Quinten the painter, residing in de Zak” who was associated with Bernard van Orley and others in the heresy investigations of 1527 in Brussels where Claes van der Elst preached. See Lorne Campbell,

National Gallery Catalogues, The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings with French Paintings Before 1600, London, 2014, p. 430.

[2] For other paintings that are possible to date by circumstantial evidence, see Silver 1984 passim and Campbell 2014, p. 431.

[3] See Stephan Goddard, “Assumed knowledge. The use of prints in sixteenth-century Antwerp workshops,” in

Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (2004/5), pp. 123–39.

[4] See above for articles on Antwerp Mannerism, and

Extravagant, A Forgotten Chapter of Antwerp Painting 1500–1530, ed. Peter van den Brink, exh. cat., Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, 2005.

[5] Dan Ewing, “Magi and merchants: the force behind the Antwerp Mannerists’ Adoration pictures,” in

Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (2004/5), pp. 287–88 n. 74.

[6] Ewing 2004/5, p. 288 and additional bibliography.

[7] Ewing 2004/5, p. 291.

[8] Ewing 2004/5, p. 291 n. 89.

[9] Joaneath Spicer, “The Lives of African Slaves and People of African Descent in Europe during the Renaissance,” in

Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, ed. Joaneath A. Spicer, exh. cat., Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1997, p. 82.

[10] Hans Rupprich, ed.,

Dürer: Schriftlicher Nachlass, 3 vols., Berlin, 1956, vol. 1, p. 167.

[11] See also Sixten Ringbom,

Icon to Narrative: The Rise of the Dramatic Close-up in Fifteenth-century Devotional Painting, rev. ed. Doornspijk, The Netherlands, 1984, pp. 90–91, 101–4, 167, 200.

[12] Aileen June Wang, “An

Adoration of the Magi after Hugo van der Goes,” in

Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, vol. 59, no. 1/2 (2000), pp. 38–45.

[13] Dendrochronology was not possible because oak strips have been added to all four sides and the panel has been cradled.

[14] Campbell 2014, p. 460.

[15] See Campbell 2014.

[16] Michael W. Kwakkelstein, “The Face as the Mirror of the Soul: Leonardo and the Moral Significance of Beauty and Ugliness,” in Michael W. Kwakkelstein and Michel Plomp,

Leonard da Vinci: The Language of Faces, exh. cat., Teylers Museum and Bussum, Haarlem, 2018, p. 36.

[17] Such decorative effects were very popular in Antwerp Mannerist paintings and were derived from prints readily available in Antwerp. Robert Koch (1992) thought that Massys’s designs were based on Daniel Hopfer designs. However, as Stephen Goddard pointed out, there were an abundance of designs available through prints that generally were not taken over wholesale by Antwerp Mannerist artists but adapted by them (see Goddard 2004/5).

[18] Silver 1984, p. 127.