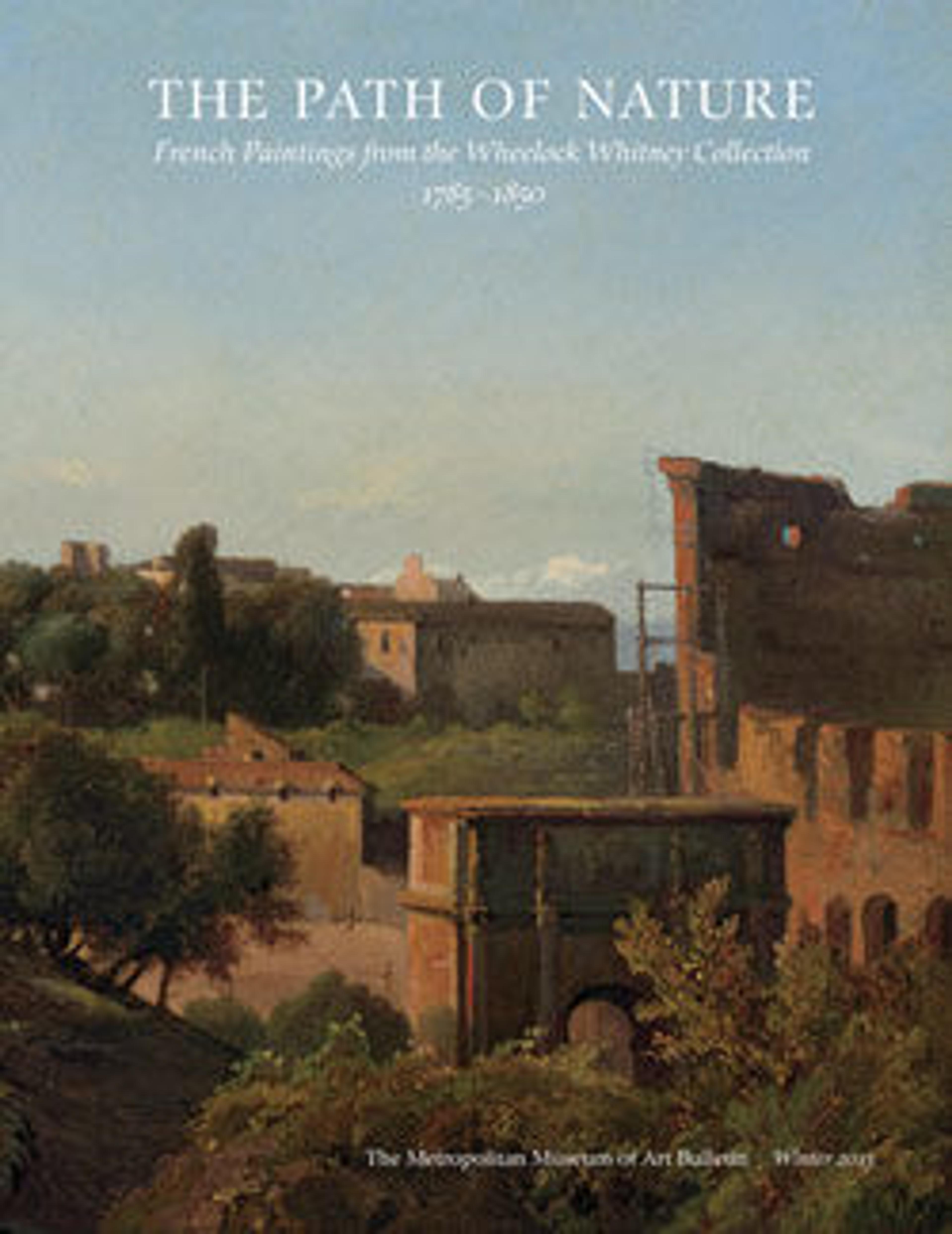

View of the Basilica of Constantine from the Palatine, Rome

For the present work, Rémond—who had been awarded the 1821 Prix de Rome in the category of historical landscape painting—set up his easel on the Palatine Hill, overlooking the Forum. Depictions of this ancient site were abundant, but Rémond set his apart by including only the rightmost of the three remaining vaults of the fourth-century Basilica of Constantine. With its controlled symmetry and free but assured brushwork, this view combines the careful composition of a finished painting with the sketchy finish of a plein-air study.

Artwork Details

- Title: View of the Basilica of Constantine from the Palatine, Rome

- Artist: Charles Rémond (French, Paris 1795–1875 Paris)

- Date: ca. 1822–25

- Medium: Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

- Dimensions: 12 3/4 x 10 5/8 in. (32.4 x 27 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Whitney Collection, Gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and Purchase, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003

- Object Number: 2003.42.47

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.