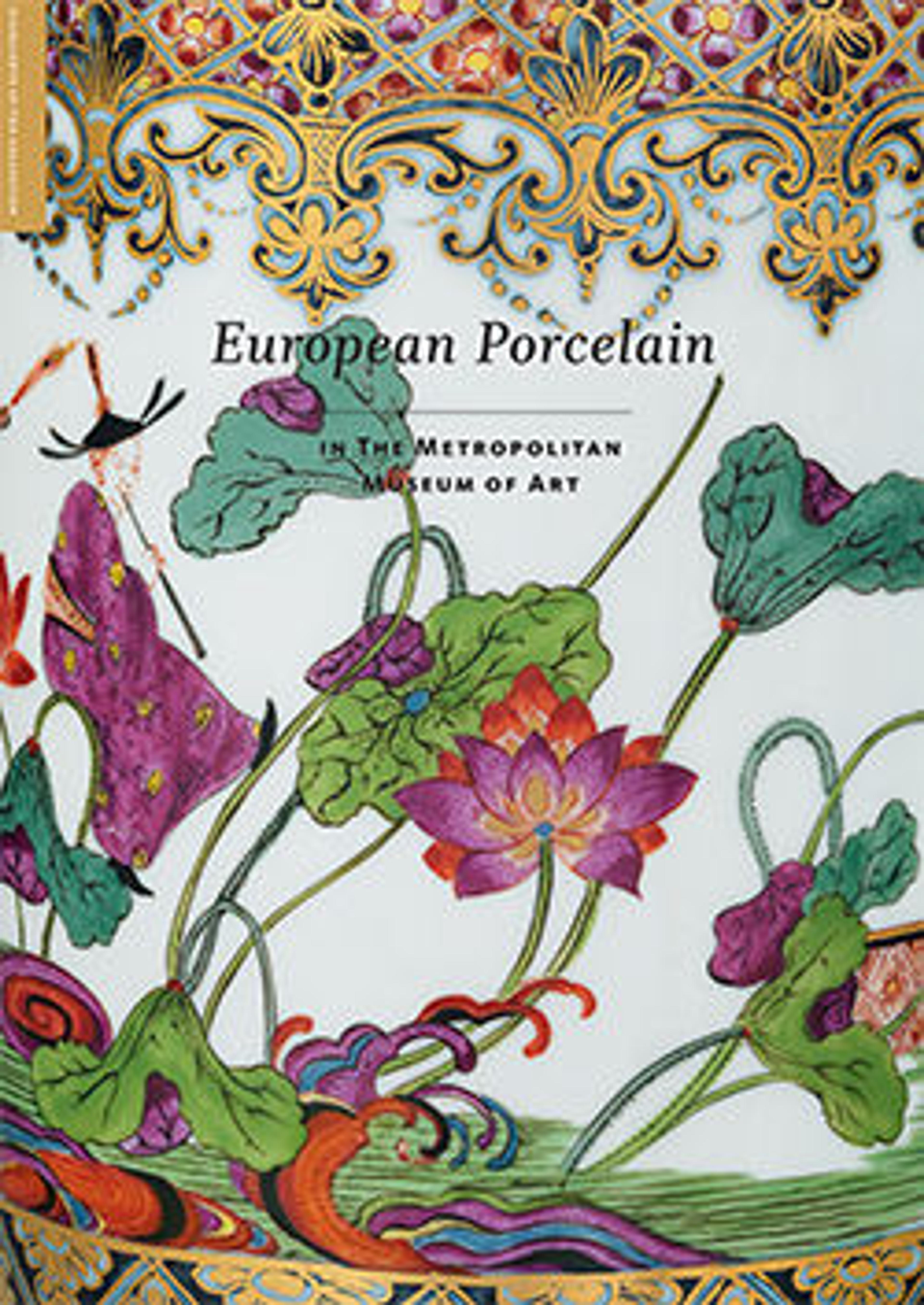

Botanical plate with spray of lilies

In the early 1750s the Chelsea factory began looking to botanical prints as sources for its painted decoration. The plants, flowers, fruits, and vegetables chosen to decorate many of the factory’s wares over an approximately five-year period beginning in 1752 constitute one of the most recognized and appreciated types of decoration employed at Chelsea during the factory’s history. Other porcelain factories, notably Meissen, had practiced botanical decoration prior to its appearance at Chelsea, but the Chelsea painters used this subject matter in an entirely original manner, which remains viewed as one of the factory’s greatest achievements. The style of the flower painting executed at Meissen in the 1740s was typically very precise and controlled, and motifs were used sparingly on large expanses of white porcelain.[1] In contrast, the botanical decoration at Chelsea was much freer and more loosely painted and often with a sensuous and almost exuberant quality. The scale of the motifs tended to be large, taking up much of the surface of the object in question, with various insects and leaves or flowers inserted around the primary motif. Leaves, flowers, fruit, and vegetables were rarely confined to the center of a plate; the borders offered additional space onto which leaves or flowers might extend or insects hover.

The porcelains produced at Chelsea and decorated in this manner have become known as the “Hans Sloane wares,” a reference to the great physician, botanist, and collector who played a highly prominent role in the cultural life of London during the first half of the eighteenth century. In 1713, Hans Sloane (Irish, 1660–1753) purchased a large tract of land in Chelsea, which included the famous botanical garden, the Chelsea Physic Garden, founded in 1673, and where Sloane had studied in the 1680s. While Sloane had no direct role in the production of the wares now associated with his name—and indeed, he died in 1753 just as the earliest wares in this style were being made—his patronage of the garden was to prove influential to their creation.[2]

While both dinner and tea wares were produced with botanical decoration at Chelsea, the vast majority of objects decorated in this manner were plates, dishes, and oval serving dishes, presumably because their largely flat surfaces were more conducive to the botanical compositions. The standard format for these wares featured a large botanical specimen that was accompanied by related attributes, such as blossoms, fruit, or seedpods with one or more butterflies or other insects added for decorative effect. Most of the primary motifs were based on botanical prints, and the painters strove for accuracy, but only to a certain extent. Leaves from another plant might have been substituted if they improved the composition,[3] the colors of blossoms were occasionally changed, particularly if they were white, and the specimen’s accompanying attributes were sometimes fanciful.

A variety of publications must have been available to the factory’s painters, but the work of one man in particular not only links a number of these publications but also reflects the influence of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) was a German artist who made a specialty of botanical illustration.[4] He worked throughout Europe and eventually in England, painting and drawing thousands of specimens. His concern for scientific accuracy, coupled with his artistic skills and talent, ensured his professional success during a period in which the appreciation of the natural sciences grew exponentially. He provided illustrations for numerous botanical publications written by different authors, and several of these publications served as source material at the factory. Ehret made his first trip to England in 1735, at which time he met both Sloane and Philip Miller (British, 1691–1771), who held the title of Curator of the Garden of Chelsea. Ehret, who soon married Miller’s sister-in-law, had extensive access to the Chelsea Physic Garden, where he drew many plants, a sizable percentage of which came from countries other than England.

It is highly likely that one of Ehret’s drawings or water-colors inspired the depiction of the lily that is the subject of the Museum’s plate, one of ten Chelsea botanical wares acquired by the Museum in 2016.[5] Ehret produced at least three different watercolor illustrations of this type of lily, which he identified as a Martagon Lily, [6] and one of his drawings was reproduced in Christoph Jacob Trew’s Plantae Selectae, a botanical publication issued in installments beginning in 1750,[7] which served as a source at the factory. The decoration on the Museum’s plate is closely related to that found on two Chelsea plates in private collections,[8] but it is not clear if all three illustrate the same type of lily, or if the differences between the depictions can be explained by artistic license on the part of the factory painters. None of the plates faithfully copies the colored engraving in Trew’s publication, but this may be due to the selective choice of motifs, or because a different source was used.

The association of Sloane with Chelsea wares and botanical decoration dates from July 1, 1758, when an advertisement appeared in a Dublin newspaper regarding the sale of a tureen decorated “in curious Plants, with Table Plates, Soup plates, and Desart Plates, enamelled from Sir Hans Sloan’s Plants. . . .”[9] This sale was one of three that took place in Dublin in 1758 in which porcelain from the Chelsea factory was auctioned, and these sales have been viewed as the factory’s effort to dispose of old stock in a market not as current in terms of fashion as that of London’s.[10] It has been suggested by Sally Kevill-Davies that linking porcelain with botanical decoration with Sloane’s name added an element of prestige to these wares, given the renown of the late patron of the Chelsea Physic Garden.[11] If the former assumption is accurate, it is notable that the popularity of botanical decoration was already fading by 1758, approximately six years after the first wares decorated in the manner were produced. By the late 1750s, changes in taste embraced more elaborate forms of decoration. Gilding and the use of ground colors were employed increasingly by the factory, and the influence of Sèvres porcelain was to play an important role in the factory’s next chapter (entry 84).

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 For example, see Cassidy- Geiger 2008, pp. 462–63, nos. 205a, b.

2 The most comprehensive treatment of the so-called Hans Sloane wares made at Chelsea is found in Kevill- Davies 2015, to which the author is much indebted. 3 Spero 1995, p. 43, no. 36.

4 Calmann 1977.

5 MMA 2016.217–.226.

6 Kevill- Davies 2015, pp. 152–53, no. 45.

7 Trew 1750–73, Decuria ii (1751), Tab. xi; ill. in Kevill- Davies 2015, p. 152.

8 Spero 1995, p. 43, no. 36; Kevill- Davies 2015, pp. 152–53, no. 45.

9 Advertisement from Faulkner’s Dublin Journal, July 1, 1758, quoted in Kevill- Davies 2015, p. 46.

10 Adams 2001, p. 112.

11 Kevill-Davies 2015, p. 46.

The porcelains produced at Chelsea and decorated in this manner have become known as the “Hans Sloane wares,” a reference to the great physician, botanist, and collector who played a highly prominent role in the cultural life of London during the first half of the eighteenth century. In 1713, Hans Sloane (Irish, 1660–1753) purchased a large tract of land in Chelsea, which included the famous botanical garden, the Chelsea Physic Garden, founded in 1673, and where Sloane had studied in the 1680s. While Sloane had no direct role in the production of the wares now associated with his name—and indeed, he died in 1753 just as the earliest wares in this style were being made—his patronage of the garden was to prove influential to their creation.[2]

While both dinner and tea wares were produced with botanical decoration at Chelsea, the vast majority of objects decorated in this manner were plates, dishes, and oval serving dishes, presumably because their largely flat surfaces were more conducive to the botanical compositions. The standard format for these wares featured a large botanical specimen that was accompanied by related attributes, such as blossoms, fruit, or seedpods with one or more butterflies or other insects added for decorative effect. Most of the primary motifs were based on botanical prints, and the painters strove for accuracy, but only to a certain extent. Leaves from another plant might have been substituted if they improved the composition,[3] the colors of blossoms were occasionally changed, particularly if they were white, and the specimen’s accompanying attributes were sometimes fanciful.

A variety of publications must have been available to the factory’s painters, but the work of one man in particular not only links a number of these publications but also reflects the influence of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) was a German artist who made a specialty of botanical illustration.[4] He worked throughout Europe and eventually in England, painting and drawing thousands of specimens. His concern for scientific accuracy, coupled with his artistic skills and talent, ensured his professional success during a period in which the appreciation of the natural sciences grew exponentially. He provided illustrations for numerous botanical publications written by different authors, and several of these publications served as source material at the factory. Ehret made his first trip to England in 1735, at which time he met both Sloane and Philip Miller (British, 1691–1771), who held the title of Curator of the Garden of Chelsea. Ehret, who soon married Miller’s sister-in-law, had extensive access to the Chelsea Physic Garden, where he drew many plants, a sizable percentage of which came from countries other than England.

It is highly likely that one of Ehret’s drawings or water-colors inspired the depiction of the lily that is the subject of the Museum’s plate, one of ten Chelsea botanical wares acquired by the Museum in 2016.[5] Ehret produced at least three different watercolor illustrations of this type of lily, which he identified as a Martagon Lily, [6] and one of his drawings was reproduced in Christoph Jacob Trew’s Plantae Selectae, a botanical publication issued in installments beginning in 1750,[7] which served as a source at the factory. The decoration on the Museum’s plate is closely related to that found on two Chelsea plates in private collections,[8] but it is not clear if all three illustrate the same type of lily, or if the differences between the depictions can be explained by artistic license on the part of the factory painters. None of the plates faithfully copies the colored engraving in Trew’s publication, but this may be due to the selective choice of motifs, or because a different source was used.

The association of Sloane with Chelsea wares and botanical decoration dates from July 1, 1758, when an advertisement appeared in a Dublin newspaper regarding the sale of a tureen decorated “in curious Plants, with Table Plates, Soup plates, and Desart Plates, enamelled from Sir Hans Sloan’s Plants. . . .”[9] This sale was one of three that took place in Dublin in 1758 in which porcelain from the Chelsea factory was auctioned, and these sales have been viewed as the factory’s effort to dispose of old stock in a market not as current in terms of fashion as that of London’s.[10] It has been suggested by Sally Kevill-Davies that linking porcelain with botanical decoration with Sloane’s name added an element of prestige to these wares, given the renown of the late patron of the Chelsea Physic Garden.[11] If the former assumption is accurate, it is notable that the popularity of botanical decoration was already fading by 1758, approximately six years after the first wares decorated in the manner were produced. By the late 1750s, changes in taste embraced more elaborate forms of decoration. Gilding and the use of ground colors were employed increasingly by the factory, and the influence of Sèvres porcelain was to play an important role in the factory’s next chapter (entry 84).

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 For example, see Cassidy- Geiger 2008, pp. 462–63, nos. 205a, b.

2 The most comprehensive treatment of the so-called Hans Sloane wares made at Chelsea is found in Kevill- Davies 2015, to which the author is much indebted. 3 Spero 1995, p. 43, no. 36.

4 Calmann 1977.

5 MMA 2016.217–.226.

6 Kevill- Davies 2015, pp. 152–53, no. 45.

7 Trew 1750–73, Decuria ii (1751), Tab. xi; ill. in Kevill- Davies 2015, p. 152.

8 Spero 1995, p. 43, no. 36; Kevill- Davies 2015, pp. 152–53, no. 45.

9 Advertisement from Faulkner’s Dublin Journal, July 1, 1758, quoted in Kevill- Davies 2015, p. 46.

10 Adams 2001, p. 112.

11 Kevill-Davies 2015, p. 46.

Artwork Details

- Title:Botanical plate with spray of lilies

- Maker:Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory (British, 1745–1784, Red Anchor Period, ca. 1753–58)

- Date:ca. 1755

- Culture:British, Chelsea

- Medium:Soft-paste porcelain with enamel decoration

- Dimensions:Overall (confirmed): 1 1/4 × 11 × 11 in. (3.2 × 27.9 × 27.9 cm)

- Classification:Ceramics-Porcelain

- Credit Line:Purchase, Sidney R. Knafel Gift, in honor of Jeffrey Munger, 2016

- Object Number:2016.223

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.