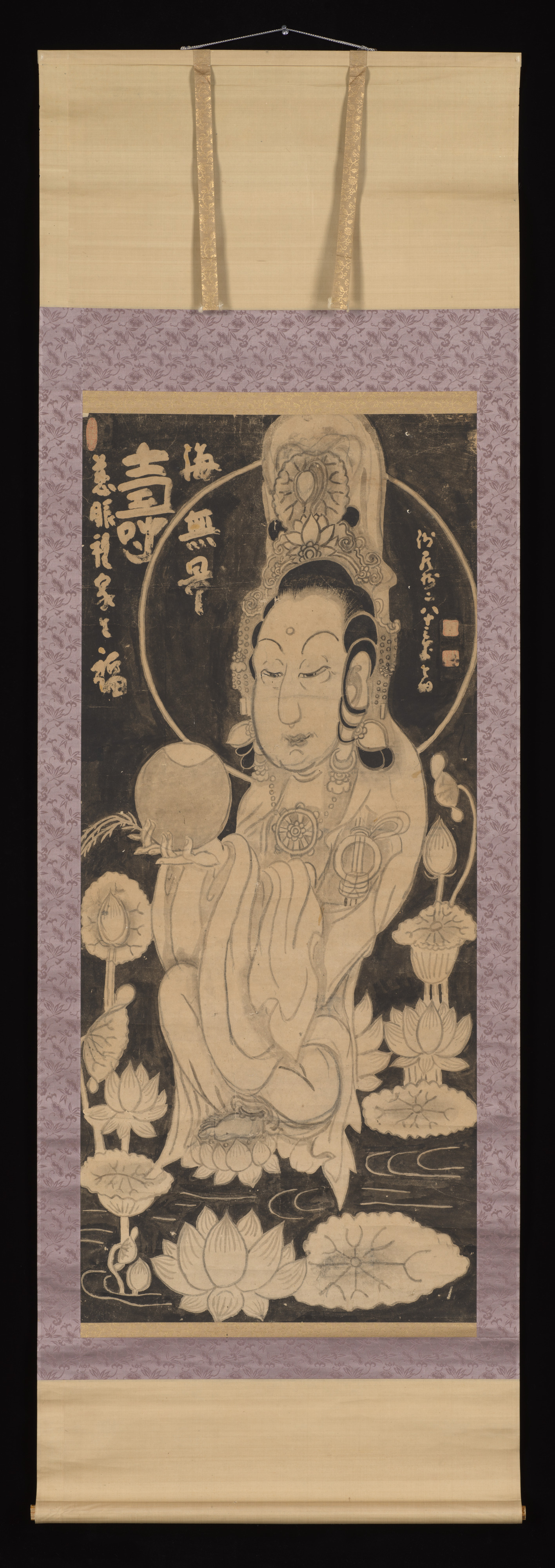

Kannon in a Lotus Pond

Hakuin Ekaku Japanese

Not on view

The Buddhist monk and prolific amateur painter Hakuin Ekaku is credited with reviving the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism after a long period of decline, and with making its teachings more accessible to the public. Born in Harajuku in Suruga province (present-day Numazu, Shizuoka prefecture), he joined the local Shōinji Temple at age fourteen. Later, after a fourteen-year pilgrimage that took him across Japan to meet various Zen masters and popularize Zen teachings, he returned to the Shōinji and remained there until his death. As a Zen master, Hakuin focused on zazen (seated meditation) and paradoxical anecdotes or dialogues called kōan, the contemplation of which may lead to spontaneous awakening. Hakuin’s bold, sometimes humorous, and altogether unprecedented paintings were an important vehicle for his teachings, which spread far beyond the monasteries and captured the minds of laypeople.

Influenced by his mother’s deep devotion to Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion, Hakuin created numerous images of the deity seated above a pond of lotus flowers, symbols of Buddhist salvation. Over the course of centuries, first in China and Korea, the originally male deity had come to be depicted in androgynous or female manifestations in early modern times. In the Zen tradition Kannon is usually depicted meditating alone on a rocky shore, referred to as White-Robed Kannon or Water-Moon Kannon. Here the bodhisattva is shown holding both a sprig of willow, which can be used as a wand to cure illness or ward off disaster, and a bowl holding either pure water or a healing nectar. Hakuin’s rendering here obscures the rocky ledge on which she is usually seated and shows the deity with her left leg folded under the right, with one foot resting on a lotus pedestal that appears to float on the surface of the pond.

This rendition of the theme is particularly striking because the central figure is rendered mostly in reserve, with strong outlines to convey the facial features and flowing robes; similarly, the lotus flowers and inscription stand out against a background that is completely inked in. The text, found on several other Hakuin depictions of Kannon, is a slight variation of the penultimate two lines of a Chinese verse near the end of the Kannon Sutra, which comprises Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra. Hakuin replaced the phrase 福聚 (fukuju, “accumulating good fortune”) in the original with the homonym 福壽 (fukuju, “good fortune and longevity”), and made the character ju 壽extra large as if to emphasize the work’s auspicious message.

慈眼視衆生 福壽海無量

Observing with compassionate eyes

all sentient beings,

And bestowing good fortune and longevity

like an ocean without limits.

—Trans. John T. Carpenter

Not only is this ink-background version of the theme quite rare, but it can also be precisely dated because the artist gave his age, 83 (82 by Western reckoning) in the signature, so we know it dates to less than two years before he died in 1769. A few other versions of this theme with inked background from the same year are known, including examples in the Sano Museum, Mishima (https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages/detail/140844) and one in the former collection of Marquis Hosokawa Moritatsu, founder of the Eisei Bunko Museum.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.