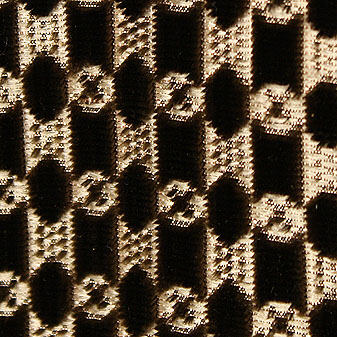

Suit

Not on view

A gentleman’s embroidered suit was a very expensive item of dress in the eighteenth century, principally because of the amount of skill and labor required to produce it. In France the guild of embroiderers carefully controlled the industry. Only a master embroiderer could make up the designs and designate the types of stitches to be used. Although women did most of the actual work, they were prevented by law from becoming masters in their field, a designation reserved for men only. Once a design was completed by the master, apprentices transferred it to the silk or velvet sheet that was already stretched on a large wooden frame. When this was laid flat, a number of embroiderers could work on a suit at the same time. An English lady visiting Lyons in 1784 left the following entry in her journal: "At the manufacture of all the very rich stuffs for furniture and for very fine embroidery. A very richly embroidered satin suit of clothes for men, about seventeen or eighteen Louis. We saw the pattern of one in velvet, with fake stones set in silver, like diamonds disposed upon it like embroidery, which they had made for Prince Potemkin, and had cost 1,000 Louis, it must have been frightfully heavy." Embroidery of garments reached its apogee in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The industry was completely disrupted by the French Revolution, and the subsequent slackening of demand for embroidered garments delivered the final blow.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.