Reflections on Golden Kingdoms and the Course of Empires

Exit view of the exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas

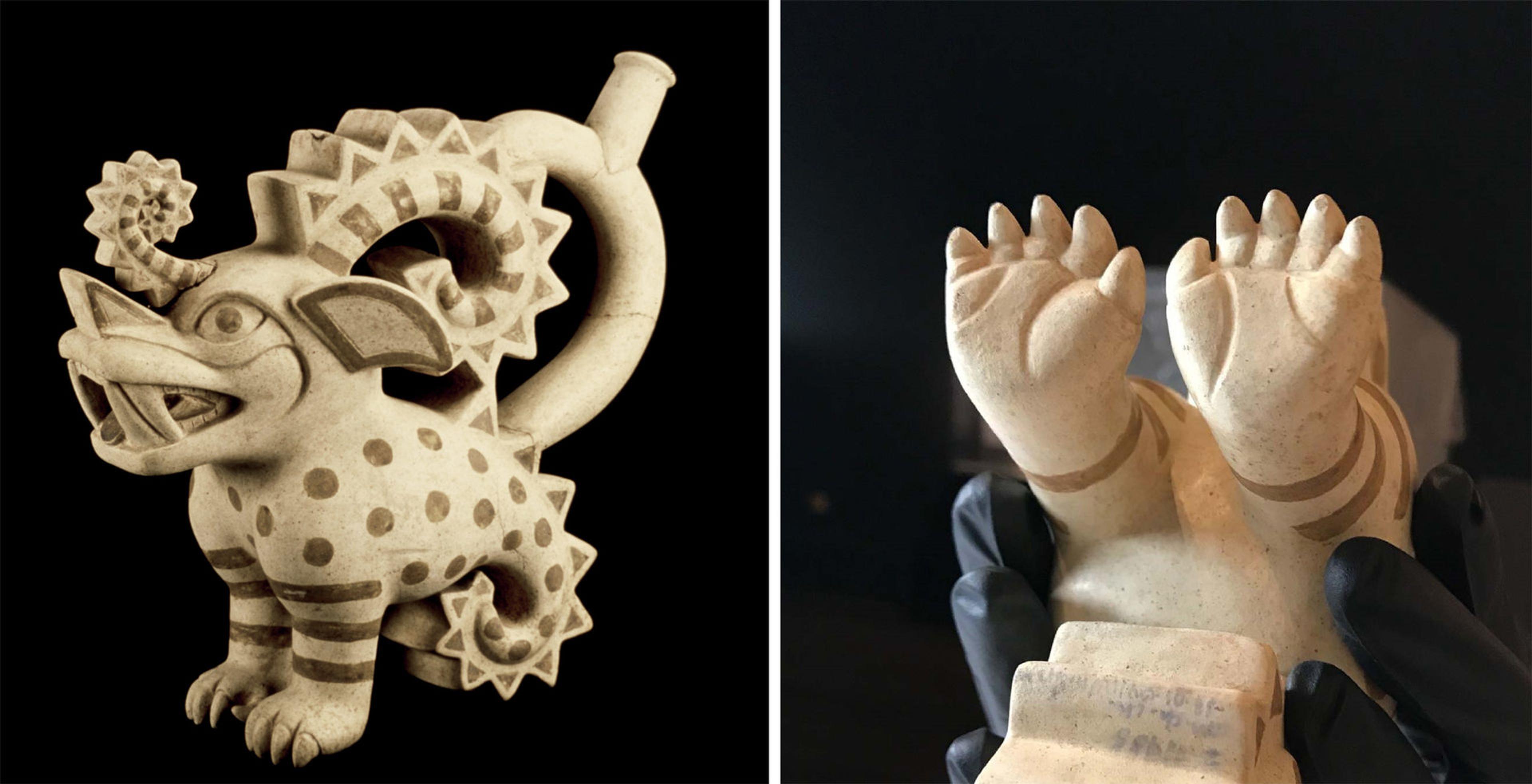

As I look back at the exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, I am struck by a few—among many—wondrous details: a bottle in the form of an imaginary hybrid creature—with features of a feline, a canine, and a seahorse—including curiously human-like palms on the normally unseen underside of the beast's clawed paws; a pendant cast in gold in the shape of dragon-like bug with a 112-carat emerald for an abdomen; and a shield ornamented with a micro-mosaic made up of some fourteen thousand tiny turquoise tesserae brilliantly arranged in gradations of deep blue to nearly white. These are but some of the small details that reveal the creative pulse of ancient American artists, details that continue to delight and amaze us centuries after their creation.

Left: Vessel in the shape of a crested animal, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Ceramic, H. 8 9/16 x W. 8 1/4 in. (21.7 x 21 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú (13-01-04/IV/A-1/13, 453). Photo by Christopher B. Donnan. Right: Detail showing the underside of the creature's paws. Photo by the author

For much of the spring, Golden Kingdoms overlapped with a beautiful and thought-provoking exhibition in the American Wing, Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings—both of which provided rich opportunities for reflections on the course of empires, the subject of one of Cole's most famous series of paintings. What survives of the civilizations that thrived in the lands that are now Latin America before the arrival of Europeans? How do we come to know the Incas, the Aztecs, and the many other cultures that flourished in these lands, many of which lasted centuries longer than has the United States? And, perhaps most importantly, how have the histories of these cultures, including our own, been generated and molded, and how do they continue to evolve?

Left: Pendant, A.D. 700–900. Panama. Coclé. Gold, emerald, H. 1 15/16 x W. 1 1/8 x D. 1 5/16 in. (5 x 2.9 x 3.3 cm). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Peabody Museum Expedition, 1933 (PM# 33-42-20/1685). Photo by Michael Cardinali. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

Golden Kingdoms featured some three hundred works, many of them small-scale objects of rare and precious materials such as gold, silver, and precious stones. But there were also numerous works made of feathers, shell, and fine cloth. Together they formed a category of art that once existed in abundance in the ancient Americas, one that was highly vulnerable to destruction at the time of the European invasion in the sixteenth century. Our view of ancient American art, therefore, has been efficiently, but misleadingly, shaped by works in more durable materials—monumental architectural complexes, stone sculpture, and ceramic vessels. Such objects were difficult to destroy entirely, unlike the fragile featherworks, or objects in metal, the most mutable of materials, so easily melted down and transformed into objects for a new god and new kings. As spectacular and sophisticated as the traditions of stone carving and ceramics were, they are only part of what once constituted ancient American art.

Left: Mosaic shield, A.D. 1400–1521. Mexico, Puebla. Mixtec (Ñudzavui). Turquoise, wood, stone, tree resin, diam. 13/16 x D. 12 13/16 in. (2 x 32.5 cm). National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (10/8708). Photo by Ernest Amoroso. Right: Detail of the tesserae

Some of these works in gold, feathers, and other precious materials were sent back to Europe after the Conquest as "curiosities," a group of which was toured throughout Europe in 1520. Among those who saw those works was the artist Albrecht Dürer, himself a trained metalsmith. He wrote in his journal:

I saw the things which have been brought to the King from the new land of gold: a sun all of gold a whole fathom broad, and a moon all of silver of the same size, also two rooms full of their equipment, also weapons, armor, darts, wonderful shields, curious clothing, bedding, and all kinds of marvelous things for various use, much more beautiful to behold than nature's prodigies. These things were all so precious that they have been valued at one hundred thousand guilders. All the days of my life I have seen nothing that has rejoiced my heart so much as these things. For I saw amongst them amazing artful objects, and I marveled at the subtle ingenia of people in foreign lands. Indeed I cannot express the thoughts that came to me there.[1]

Alas, Dürer left us no sketches of these works, and their later histories and whereabouts are unknown. But some other works sent to Europe in the middle of the sixteenth century have been identified. A spectacular mosaic mask of a Mixtec goddess, for example, ended up in the collections of Cosimo I de' Medici, duke of Florence. Such survivals are, however, mere flickerings of what has been lost, like a single leaf from a glorious autumn's bounty.

Mask, A.D. 1200–1521. Mexico. Probably Mixtec (Ñudzavui). Turquoise, wood, mother-of-pearl, shell (Spondylus princeps, Spondylus calcifer). MiBACT Museo delle Civiltà – Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico "L. Pigorini" (4231). Photo archive scans by Mario Mineo

Most works of feathers, gold, silver, and other materials were destroyed on a colossal scale, either intentionally or through neglect, in the sixteenth century and beyond. Chan Chan, the great capital of the Chimú culture (A.D. 1000–ca. 1472) on Peru's North Coast, once famed for its brilliant metalsmiths, was subjected to systematic looting in the sixteenth century: Colonial authorities granted what amounted to mining rights, which allowed the pillage of pre-Hispanic tombs, as long as the Royal Fifth—the twenty percent of booty owed to the Spanish king—was paid. Most works of Precolumbian art in metal were melted down, yet, extraordinarily, rare survivals have come to light, such as a set of gold and silver goblets from Chan Chan that somehow escaped the notice of the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. These elegant vessels were excavated in the twentieth century, by which time their interest as a connection to ancient civilizations outweighed their value as raw material.

Three goblets, A.D. 1200–1470. Peru, Chan Chan. Chimú. Silver, gold. Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú (M-3401, M-6656, M-6660). Photos by María del Rosario Jhong

The thirst for precious metals in the ancient Americas was ultimately the accelerant to the massive destruction of indigenous communities. The European quest for metals eventually led to a devastating loss of native American life, as disease and grueling conditions in the mines took their toll on the native populations forced to labor in them. The destruction of ancient American works of art was also fueled by a genuine concern over the power of idolatry. Campaigns were mounted to destroy any vestiges of indigenous religious practices, and incalculable numbers of objects were rooted out and destroyed or buried in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Luxurious Mesoamerican books were burned as instruments of the Devil. The Codex Zouche-Nuttall, an exquisitely painted illuminated manuscript, is one of a handful of Precolumbian books to survive to the present day. Painted on deerskin primed with gesso, the manuscript relates the dynastic history of Lord 8 Deer Tiger's Claw, an eleventh-century Mixtec ruler.

Codex Zouche-Nuttall, page 85 (obverse), A.D. 1450. Mexico, Western Oaxaca. Mixtec (Ñudzavui). Deerskin, gesso, pigment, closed: 7 1/2 in. x 9 1/4 in. (19 x 23.5 cm); open: 37 ft. 4 13/16 in. (11.4 m). British Museum, London (MSS 39671). © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Lest we look upon this with a "this can't happen here" sense of shock, the Christian Reformation in Europe—exactly contemporary with the destruction of the Precolumbian books—saw similar catastrophic pillaging and destruction that arose from the antagonism between Protestants and Catholics. The anti-Catholic policies of England's Henry VIII, for example, led to the systematic destruction of beautiful monastic complexes throughout the country along with the works of art they contained. The image of autumnal trees as "bare ruin'd choirs," as referred to by Shakespeare in his Sonnet 73, was surely a general meditation on the fragility of life but also a visceral evocation of the relatively recent destruction that penetrated even the quietest valleys in the English countryside and turned once-exquisite churches into mere haunted shells.

Exhibitions are great drivers of research, from the initial studies that eventually lead to the preparation of a catalogue, to continued observations during the installation of the works, and through discussions with visitors when the exhibition is on view. Astute comments and questions from the public prompt further reflections on many topics, including the very nature of the creation of histories. Golden Kingdoms has been an acute reminder of the ways in which we try to understand the past, and the sharp distinctions between what we know from historical texts and what we know from archaeology and the objects themselves.

It has become a platitude to say that history is written by the victors, but the official histories of the ancient Americas were written decades after the glittering cities of these cultures had been destroyed and their populations devastated. Many were composed to justify the Conquest, to present the indigenous populations of the ancient Americas as benighted, and in desperate need of salvation. These histories continue to cast a surprisingly long shadow onto present-day understandings of the history of Latin America before the arrival of Europeans.

Archaeology is an antidote, or at least a complementary means, by which to view the past. What we know from archaeology is distinct from what we know from historical sources. We know more about populations that are under-addressed in the written texts, such as women, and populations in the provinces. But we also know about the striking achievements of some of the greatest artists of the ancient Americas, who, just like their contemporaries in Europe, were working for the great patrons of their time. These precious works that were part of Golden Kingdoms, exceedingly rare testaments to the brilliance of ancient American courts and their artists, remind us of the fragility of all cultures. It is in these deeply resonant works, these tangible connections to worlds now almost entirely lost to us, that the great imagination and artistry of ancient Americans lives on.

Note

[1] William Conway, ed., with amendments by Hanns Hubach, The Writings of Albrecht Dürer (London: Peter Owen Limited, 1958), 101–102.

Related Content

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas was on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from February 28 through May 28, 2018.

See more digital content related to Golden Kingdoms, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition in English and in Spanish.

Read more articles in this exhibition's blog series.

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.

Joanne Pillsbury

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of Ancient American Art, is a specialist in the art and archaeology of the Precolumbian Americas. Pillsbury earned her PhD from Columbia University. She was previously Associate Director of the Getty Research Institute and Director of Precolumbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks. She is the author, editor, or co-editor of numerous publications, including the three-volume Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900 (2008), the Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Award recipient Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks (2012), and Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas (2012), which was awarded the Association for Latin American Art Book Award.