From the seventeenth century to the present, handheld fans have been used as souvenirs to commemorate events and to remember visits to important sites. Printed fans could be distributed to large groups, while painted ones were designed for more exclusive clientele. In the late nineteenth century, advances in printing technology and a growing population of middle-class consumers gave rise to advertising fans. By the first decades of the twentieth century, fans publicized department stores, perfume, champagne, alcohol, hotels, and restaurants. Works in The Met collection trace this long history of fans as instruments of memory, whether as mementos of travel and major events, or reminders of products and services.

Jacques Callot (French, 1592–1635). L'Eventail (The Fan) and detail, 1619. Etching and engraving; second state of two, 8 5/8 x 11 7/8 in. (21.9 x 30.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1961 (61.546.2)

One of the earliest surviving fan designs signed by a renowned artist is Jacques Callot’s print commemorating an elaborate celebration for the feast day of Saint James in Florence. The acclaimed French printmaker spent his early career in Italy and was commissioned by Cosimo II de’ Medici to produce this fan in an edition of five hundred. When cut out and mounted, the fan included text on the reverse to explain the day’s events, which featured a mock naval battle on the Arno River visible in the scene. In a clever mise en abyme, one of the spectators seated on the curving form of the baroque frame at right holds aloft an example of the mounted fan.

Fan Design with Views of Mount Vesuvius and the Tomb of Virgil, 1779. Italian. Opaque watercolor on parchment, 11 in. × 21 5/8 in. (28 × 55 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1938 (38.91.104)

As travel increased in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, fans became popular as small, practical, and artistic objects that served as keepsakes. In Italy, a new genre developed in the late eighteenth century to appeal to travelers undertaking the Grand Tour. Naples was a major center of production for these hand-painted fans, which frequently featured Mount Vesuvius—particularly active during this period—as a primary subject. Early tourists often purchased unmounted fan leaves, probably intending to affix them to sticks upon their return home. Some never did, so The Met’s collection features both flat and mounted examples.

Folding Fan with a Representation of the 1806 Eruption of Mount Vesuvius (recto/verso), ca. 1815. Italian. Opaque watercolor on parchment; mother-of-pearl with spangles, 7 5/8 x 15 1/4 in. (19.4 x 38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mrs. George Clinton Genet, 1914 (14.73)

An unmounted fan leaf shows the 1779 eruption of Vesuvius in a dramatic nighttime view flanked by daylit scenes of the smoldering volcano and Virgil’s tomb. A fan mounted on mother-of-pearl sticks decorated with spangles bears two spectacular nocturnal views of the 1806 eruption. One side shows the volcanic flare as seen from across the bay, while the other gives a view from the hillside where a lurid orange stream of lava bends—seemingly to accommodate the curved format of the fan—flowing across the fan’s lower arch. For an affluent Grand Tourist in the early nineteenth century, these fans were high-end mementos of a visit to Naples, even if an eruption was not witnessed firsthand.

The Universal Exhibitions of the second half of the nineteenth century were major events for the promotion of national arts and industries. French fan makers distinguished themselves from the start, winning the highest honors at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. Souvenir fans were produced for every fair, providing visitors with information and maps while also depicting the remarkable buildings erected specifically for these occasions.

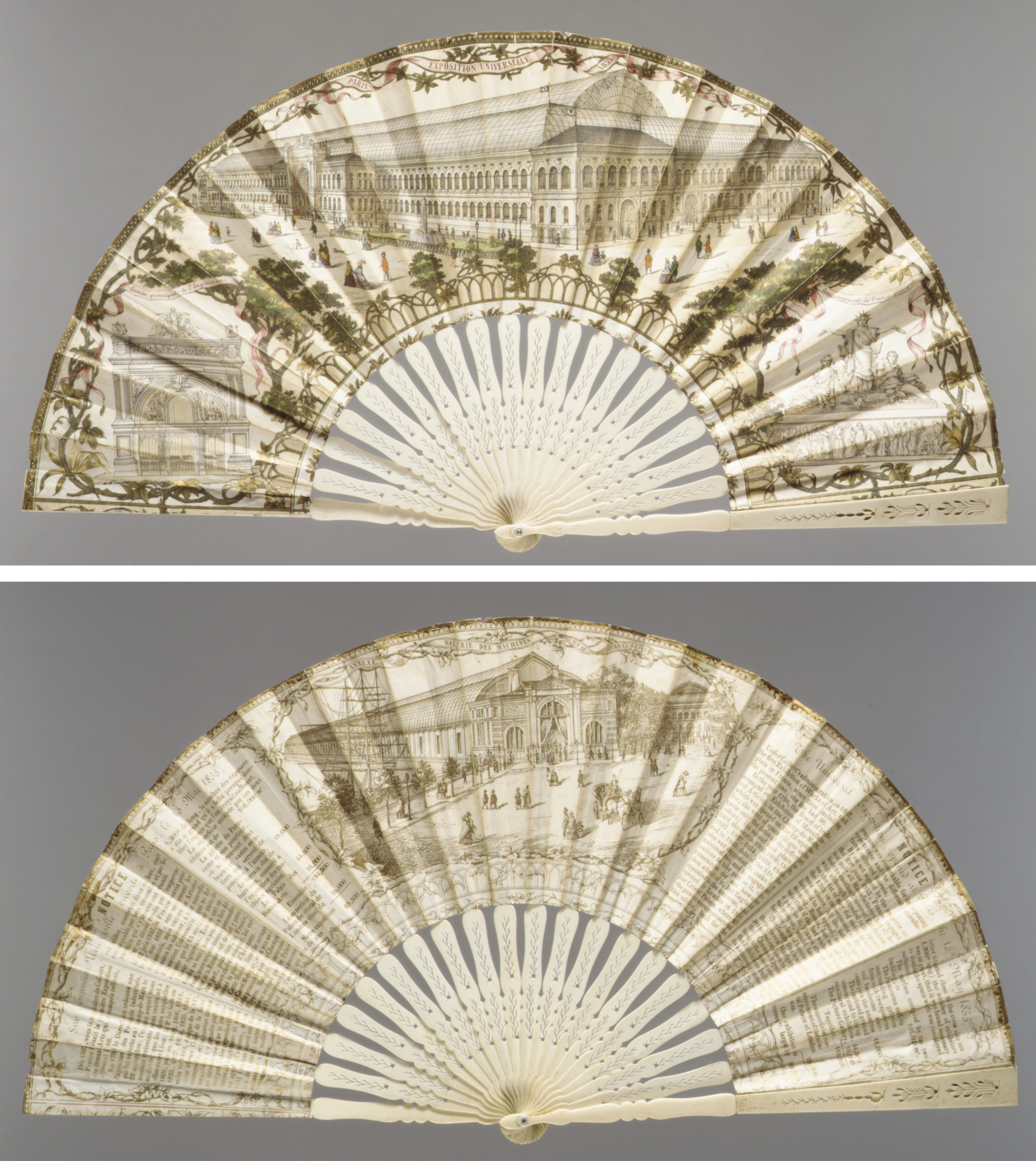

After a design by Alphonse Guilletat (French). Fan commemorating the 1855 Universal Exhibition (recto/verso), 1855. Hand-colored lithograph printed in metallic ink; ivory and mother of pearl, 10 3/8 x 19 3/4 in. (26.4 x 50.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Thomas Hunt, 1933 (33.82.14)

A commemorative fan from 1855 features the massive Palais de l’Industrie (on the site of today’s Grand Palais), erected for the Universal Exhibition in Paris that year. The reverse side presents the Galerie des Machines, a vast annex that contained the continuation of the exhibition, along with facts and figures about the event. The text appears in both French and English and compares the overall scale of the French display buildings with London’s Crystal Palace, highlighting the competition between nations. The official catalogue described the fan industry in France as “advanced and flourishing,” offering something for everyone, from fans costing as little as three cents to those of the highest luxury.

Top: Alejandro Sans (Spanish, active late 19th century). Fan leaves for the Universal Exhibition of 1889, 1889. Color lithographs, 13 in. × 25 7/8 in. (33 × 65.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1938 (38.91.121 and 38.91.120). Bottom: Alejandro Sans (Spanish, active late 19th century). Souvenir from the Universal Exhibition, Paris 1889 (recto/verso), 1889. Color lithograph mounted on wood sticks, 12 3/4 x 8 in. (32.4 x 20.5 cm). Musée Carnavalet, Paris

As the century progressed, the number and scale of the fans produced for each fair increased. Two large-format fan leaves designed as tokens of the Universal Exhibition of 1889 in Paris were recently identified as belonging to the same fan project thanks to a mounted version of the fan at the Musée Carnavalet. (The Spanish fan maker’s name appears on only one of the sheets, so this discovery also enabled an attribution for the design.) One side depicts the buildings erected for the event, which included the Eiffel Tower, shown enlarged on an unfurled map of the fairgrounds on the left bank of the Seine. The reverse features other monuments that visitors to Paris might like to see, including the Palais de Trocadéro, built for the Universal Exhibition of 1878; the new opera house designed by Charles Garnier and inaugurated in 1875; and the Château de Versailles.

Utagawa Hiroshige II (Japanese, 1826–1869). View of Iris Gardens at Horikiri, 1861. Woodblock print (aizuri-e), 8 3/8 x 11 1/4 in. (21.3 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.279)

The use of the fan to depict well-known tourist sites was a practice found in Japan as well as Europe in the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A fan design (or uchiwa-e) by Utagawa Hiroshige II, the son-in-law of the great color woodblock print artist Utagawa Hiroshige, shows a nighttime visit to the famous Edo period iris garden at the Horikiri Shrine in Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The blues both suggest a nocturnal scene and are associated (aptly for a fan) with coolness. Prussian (or Berlin) blue, first brought to Asia from Europe in the mid-eighteenth century and popularized in Japan around 1830, became the dominant color in late Edo landscape fans. From 1840 to 1868, “semi-aizuri” examples—as here, with its subtle touches of pink—became more common than the earlier pure aizuri-e (blue-printed) fans. The print could have been mounted to a split bamboo frame with a handle to make a functional uchiwa (or fixed fan), but fan-shaped woodblock prints were also produced and collected as artworks with no intention of mounting. In Japan, uchiwa fans were cheaply available, requiring less labor and materials than folding fans (ōgi). The opposite was true in France, where they were more expensive and prized as imports for their novel format.

Top: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Chemins de Fer de l’Ouest, sur la plage, 1900. Color lithograph, 13 1/4 × 24 1/4 in. (33.5 × 61.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1938 (38.91.115). Bottom: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Chemins de Fer de l’Ouest (recto/verso), 1900. Color lithograph mounted on wood sticks, 11 7/8 x 22 in. (30 x 56 cm). Private collection

Following the expansion of railway networks and the exponential growth of the tourism industry in the late nineteenth century, French railroad companies commissioned fans that promoted rail travel and holiday destinations. As useful, handheld accessories for travelers on a journey, the fans also provided practical information about train lines and tickets. A design by the Swiss-born French painter, printmaker, and illustrator Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen for the Chemins de Fer de l’Ouest publicizes special excursion rates to the seaside, featuring two elegant women seated at the shoreline, watching a child play in the sand. The white day dress worn by one of the women flows past the traditional confines for a fan leaf’s image and forms the void of the fan’s lower arch. This innovative use of negative space is best appreciated in the unmounted fan leaf. A mounted version of the fan in a private collection shows the variety of advertisements that featured on the reverse, including books for reading by the sea and travel guides.

Fan with bullfighting scenes (recto/verso), late 19th–early 20th century. Spanish. Color lithograph; wood, 10 5/8 x 19 1/2 in. (27 x 49.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Estate of Mary Le Boutillier, 1945 (C.I.45.79.74)

Fans were especially popular among visitors to Spain, which became a center of fan production in the nineteenth century, following the establishment of a royal fan factory in Valencia in 1802. Reporting from his travels to the Iberian Peninsula in the early 1840s, the French writer Théophile Gautier claimed, “A woman without a fan is something I have not yet seen in this happy country.” The prominent role of the fan in Spanish flamenco dance is likely another reason it became inextricably linked with Spain in the nineteenth-century imagination at a time when Spanish culture was increasingly exported throughout Europe. The guard sticks of touristic fans, such as an example featuring bullfighting scenes, were often inscribed with “Recuerdo España,” or “I remember Spain.” The border decoration of this fan evokes Andalusian polychrome tiles and architectural decoration.

Left: Eventails Choumara (French, active early 20th century). Yvette Guilbert fan, 1903. Color lithograph; wood, silk, 11 ¼ x 13 ¾ in. (28.6 x 34.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Milton W. and Blanche R. Brown, in memory of Polaire Weissman, 1992 (1992.167.2a, b). Right: E. Gendrot (French, active late 19th–early 20th century). Fan, 1930. Color lithograph; wood, 11 ½ x 12 in. (29.2 x 30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.56)

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Art Nouveau designers employed the signature serpentine lines of their graphic style to produce souvenir fans serving a variety of functions. The fan maker Eventails Choumara specialized in fans featuring celebrity performers. One example displaying a profile portrait of Belle Epoque French cabaret singer Yvette Guilbert commemorates the Annual Lawn Tennis Ball and Cotillion at the Grand Hotel Engadiner Kulm (Kulm Hotel St. Moritz today) and served a dual-purpose as a dance card on the reverse. A small pencil attached by a string could be used to note dance partners.

For the major fan maker Duvelleroy, Gendrot created a design celebrating champagne around 1900. Against a background of grapevines, a woman festooned with grapes in her hair raises a glass. The fan was evidently still in production thirty years later, as the version in The Met collection is inscribed by the souvenir fan collector Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen as acquired at the Ritz Hotel in Paris on Sunday evening, June 7, 1930.

Top: Antoine Calbet (French, 1860–1942). Fan advertising the Hotel Crillon (recto), 1921–1922. Color lithograph; wood, 8 ⅝ x 15 ⅞ in. (21.9 x 40.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.43). Bottom: Antoine Calbet (French, 1860–1942). Fan advertising the Grands Magasins du Louvre (recto), ca. 1922. Color lithograph; wood, 9 x 12 ⅛ in. (22.9 x 30.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.34)

Before concepts of exclusivity had entered the advertising marketplace, the same design could be issued for multiple clients. The painter Antoine Calbet’s scene of women promenading on a flower-filled terrace appears on two fans in The Met collection. The verso of one fan is inscribed "Hotel Crillon" (Hotel de Crillon today), the storied luxury hotel that opened in an eighteenth-century Neoclassical building on the Place de la Concorde just over a decade before the fan’s making. Another fan featuring an identical illustration notes that it was given away to shoppers at the Grands Magasins du Louvre department store. The latter was produced in the “balloon” format, a shape that became popular in the early twentieth century.

Jean Gabriel Domergue (French, 1889–1962). Fan advertising Royal Origan perfume (recto/verso), 1921. Color lithograph; wood, 9 ¾ x 10 in. (24.8 x 25.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.19)

Department stores produced many of the early twentieth century advertising fans. A design by Jean Gabriel Domergue, a painter of Parisian women, positions a short-haired flapper surrounded by floating luxuries. Feathered fans join flowers, hats, gloves, and perfume bottles fancifully flying around the woman, lost in reverie. The fan’s other side reveals the cause of her contentment: Royal Origan perfume, advertised as a “parfum ultra-subtil" (ultra-subtle fragrance), the “dernière creation” (latest creation) from the Galeries Lafayette department store, which had opened its doors in 1893.

Left: Advertising fan for the Galeries Lafayette, 1927. French. Lithograph; wood,10 ⅛ x 8 in. (25.7 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.13). Right: Advertising fan for the Galeries Lafayette, ca. 1920s. French. Color lithograph; wood, 9 ¾ x 9 in. (24.8 x 22.9 cm). Gift of Mrs. DeWitt Clinton Cohen, 1939 (C.I.39.79.52)

In the 1920s, the concept of using fans to advertise directly to women with disposable incomes caught on. Two fans advertising stockings (“Le Bas”) at the Galeries Lafayette provide pricing information and the stocking colors carried by the store. Images of stockinged legs bared to the thigh aimed to sell through sex appeal, a new tactic in advertising that targeted women in the period. A design dated to 1927 with strong capitalized lettering cascading down the face of the fan and a sharp contrasting gold-and-black background is characteristic of Art Deco style. A related design from about 1930 places a pair of pale stockinged legs against a raucous red, pink, orange, and gold background. It offers stockings at two price points: artificial silk (“Gina”), described as “economical, strong, and elegant” at a price of 29.50 francs, and natural silk ("Rym”) of “incomparable fineness and quality” for forty-eight francs. A woman’s face depicted on the back declares, “I buy everything at Galeries Lafayette,” a clear advertising ploy to get women to consider purchasing small luxuries like stockings at the department store.

Whether serving as reminders of the Grand Tour or Universal Exhibitions or advertising new train lines, champagne, or stockings, fans have played a significant role in cementing fond memories, disseminating information, and creating brand recognition. Although today’s handheld fans are increasingly mechanized, folding fans are still distributed or sold at crowded sporting events and concerts, usually featuring the name of a sponsor, team, or musical act. Their purpose is always at least twofold: to supply a cooling breeze and serve as a keepsake of memorable experiences.

This essay is published in conjunction with the exhibition Fanmania on view through May 12, 2026.