Lives of the Gods

Divinity in Maya Art

The ancient Maya revered a multitude of gods and goddesses who ruled over aspects of the world, from the cycles of day and night to the ownership of the earth’s resources, including rain and agricultural bounty. Images of the gods’ mythical lives and primeval struggles—struggles that resulted in the formation of the world and its inhabitants—endure in the art of the Classic period (A.D. 250–900). Caring for the gods was a primary duty of kings and queens, who modeled their deportment on the deities. In Maya writing, these monarchs were referred to as “godlike” or “sacred” (k’uhul), from the hieroglyphic sign k’uh, for deities, sacred substances, and objects. Rulers commemorated their close connections to divinity in elaborate works of art.

This exhibition brings together objects that honor the extraordinary talent of Classic-period Maya artists, some of whom signed their work. Inspired by the gods’ mythical actions, artists inventively explored the origins of the sun, the moon, maize, and royal dynasties in monumental sculpture as well as in delicate ornaments and ceramics. Understanding of these objects’ profound religious meanings has advanced significantly in recent decades, thanks to leaps in the decipherment of Maya writing, nuanced interpretations of mythical sagas recorded shortly after the Spanish invasion in the sixteenth century, and collaborative research with contemporary Maya peoples.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Creations

To the Maya, creation was an extended process shaped by waves of chaos and new beginnings. Inscriptions date the lives of the gods to very ancient times, sometimes hundreds of thousands of years in the past. Gods were born and enthroned as kings of divine realms, but they were beset by struggles. Hieroglyphic texts tell of the killing of primeval creatures, which set in motion floods and other disasters that signaled the ends of eras. Detailed colonial-period accounts from Guatemala and Yucatán likewise place the actions of the gods in deep history, and describe ancient epochs destroyed by cataclysmic events.

Inscriptions on stone sculptures and ceramics highlight specific foundational events that occurred around August 11, 3114 B.C., a mythical date well before the advent of cities and writing in this part of the world. On this date, inscriptions say that deities "were set in order"—placed in a row—and the gods put stones in mythical locations. Maya kings replicated these divine actions at celebrations marking the ends of calendrical periods, each calculated at regular intervals from 3114 B.C., in emulation of the primordial acts of the gods.

All drawings by Mark Van Stone.

Itzamnaaj

How we read the name glyph for the elderly celestial god in ancient Maya religion is still uncertain. One possibility is Itzamnaaj, the name of a major deity in colonial Yucatán. The spelling of this important god’s name may have evolved through the centuries.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Day

Maya mythical narratives describe the unhappy lives of the first people, who suffered in cold darkness and trod on a soggy earth dominated by vicious creatures. These people welcomed the first glorious sunrise, which dried the earth and marked the beginning of a new era with regular cycles of night and day. Unable to stand the heat of the sun, the primeval creatures of the previous era died or receded into the darker fringes of the world, allowing communities to settle down, raise crops, and prosper.

The struggles among gods in primordial times were favored subjects for Maya artists. Painters and sculptors paid great attention to the confrontation between a young solar god and a monstrous bird, one of the vicious creatures who opposed the rise of the sun. This great bird was eventually defeated, but came to be revered as a god, overlapping with the elderly celestial god Itzamnaaj.

The sun was associated with life-giving forces, and rulers identified closely with this power, often adding the title K’inich, or Sun God, to their name. Deceased kings were often portrayed as glorious new suns rising in the sky, overseeing their successors’ performance of royal and religious duties.

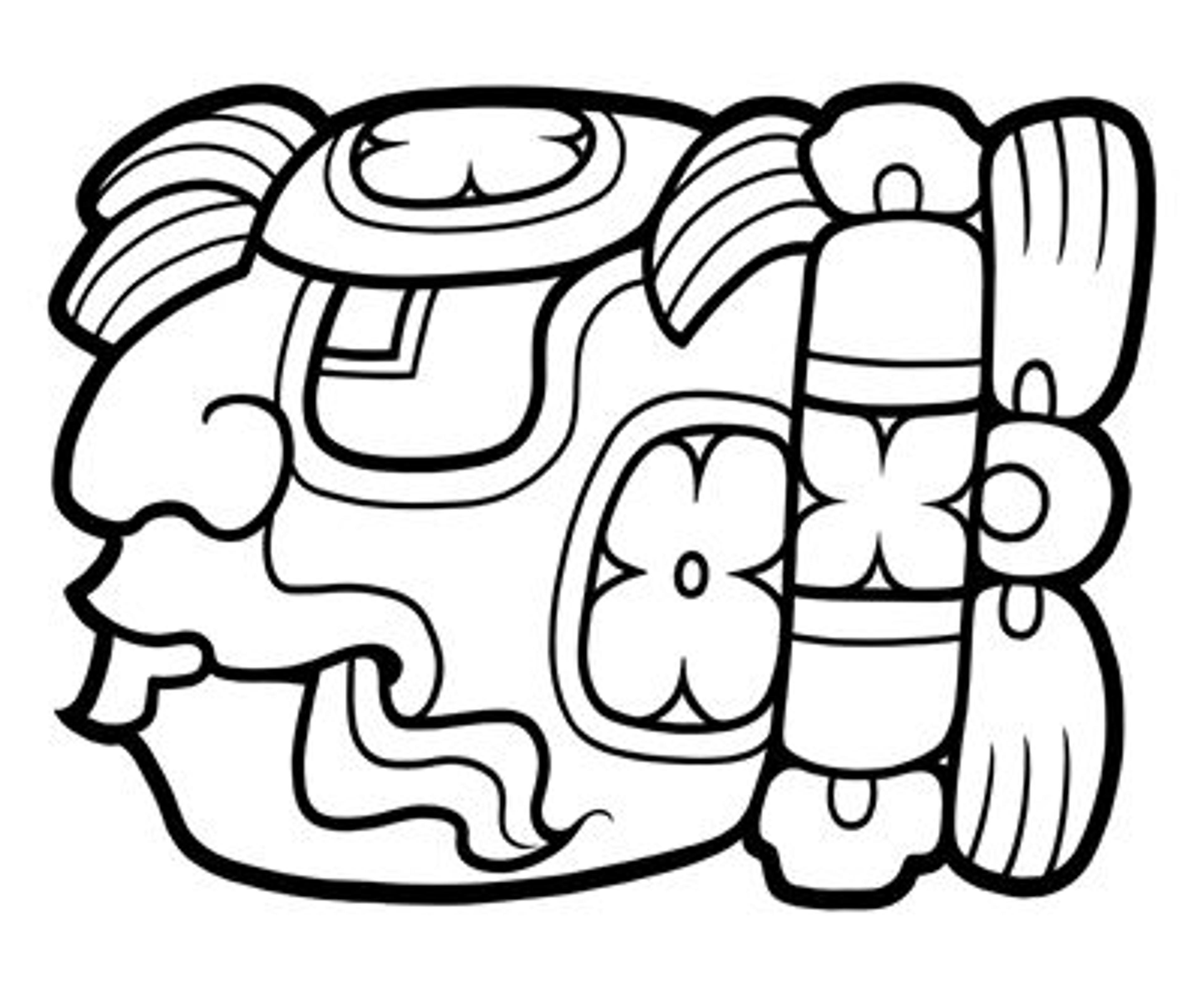

Sun God

The name of the Sun God, K’inich, derives from k’in, a term that refers to the sun and the day, as well as to heat and things that are hot.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Night

Night and darkness are the domains of the disorder that prevailed before the sun first rose. While sunset is associated with decay and death, nighttime is also related to fertility. Maya peoples liken the remains of the dead to seeds that carry the promise of rebirth and sprout from the dark interior of the earth.

Maya artists excelled at creating imaginative, often terrifying images of nocturnal deities. Jaguars, active after dark and the most powerful carnivores in the Maya area, figure prominently in representations of nighttime gods. Of the multiple jaguar gods and goddesses, all had aggressive, warlike personalities. Yet they were sometimes overcome and mocked in mythical encounters by younger and less imposing deities.

Nocturnal deities could also be beautiful. Maya artists depicted the Moon Goddess as a young woman, who was sometimes identified in texts as the sun’s wife or mother. She, along with other goddesses, was broadly associated with reproduction, as well as with the textile arts of spinning and weaving.

Jaguar God

The names of deities are frequently rendered as profiles of the gods themselves. The glyph for the jaguar god of night, fire, and warfare combines human and jaguar features, together with marks that denote it as a nocturnal deity. The reading of this name remains uncertain.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Rain

Chahk, the god of rain and storms, was venerated throughout the Maya region, and acts of appeasement to him were, and still are, critical for the well-being of communities. Water is a scarce resource in the Maya Lowlands, and the inhabitants of ancient cities survived the long dry season by storing rainwater in reservoirs. They also suffered periodically from excessive rains and wind brought by hurricanes. A capricious, unpredictable god, Chahk was often depicted brandishing an axe in the shape of K’awiil, a deity that personified lightning. While both Chahk and K’awiil were portrayed with humanlike bodies, certain features are decidedly fantastic, such as large spiral eyes, long fangs, and reptilian scales.

K’awiil himself was often depicted with a smoking axe through the forehead and a serpentine left leg. This powerful deity was related to ideas of abundance: lightning strikes were thought to fertilize the earth. K’awiil had power over the reproductive forces of living creatures, including plants and people, and all forms of wealth and abundance. He was often held by rulers in the form of a scepter or axe decorated with his likeness, a symbolic link between kings and queens and the power of lightning, fecundity, and wealth.

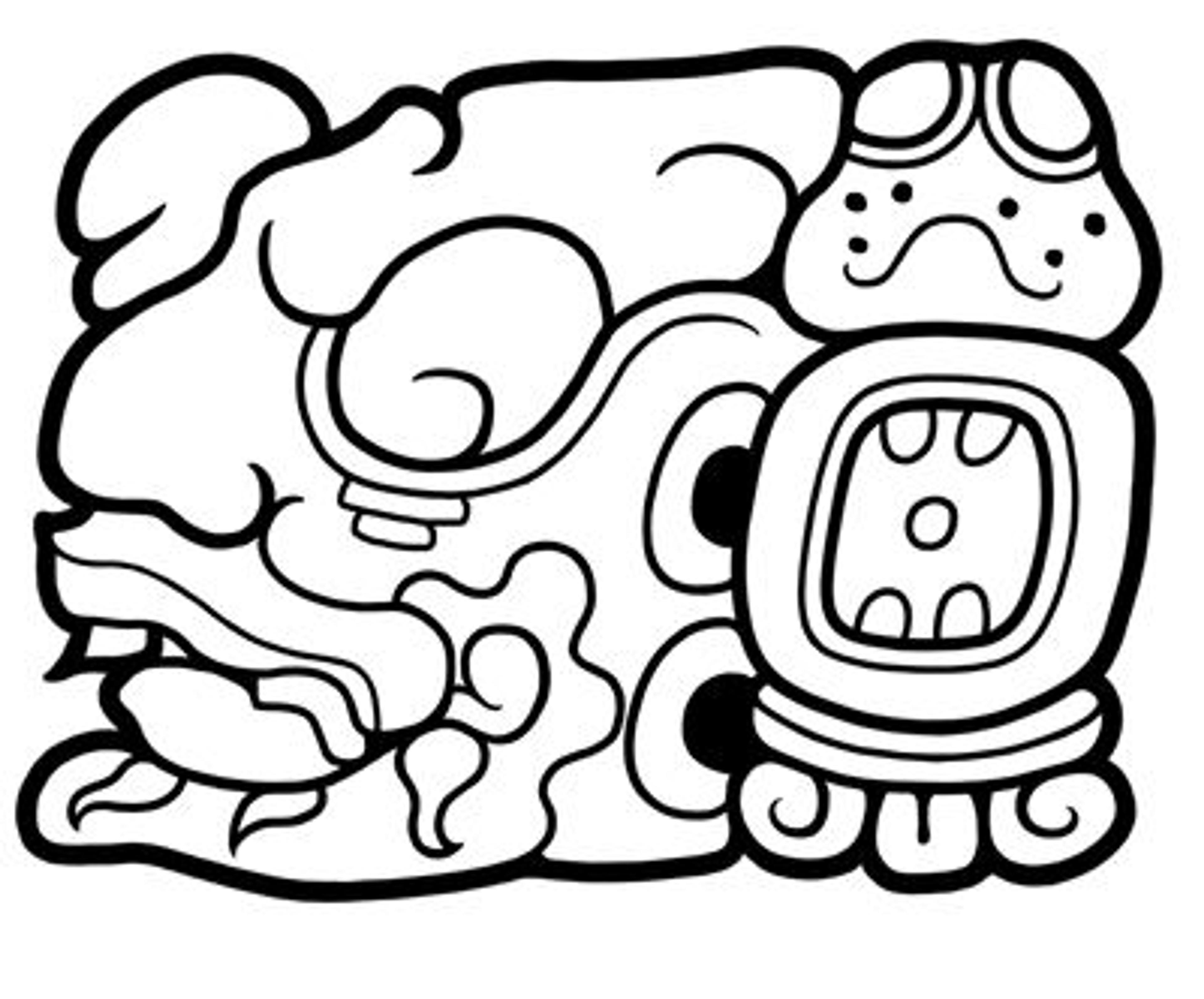

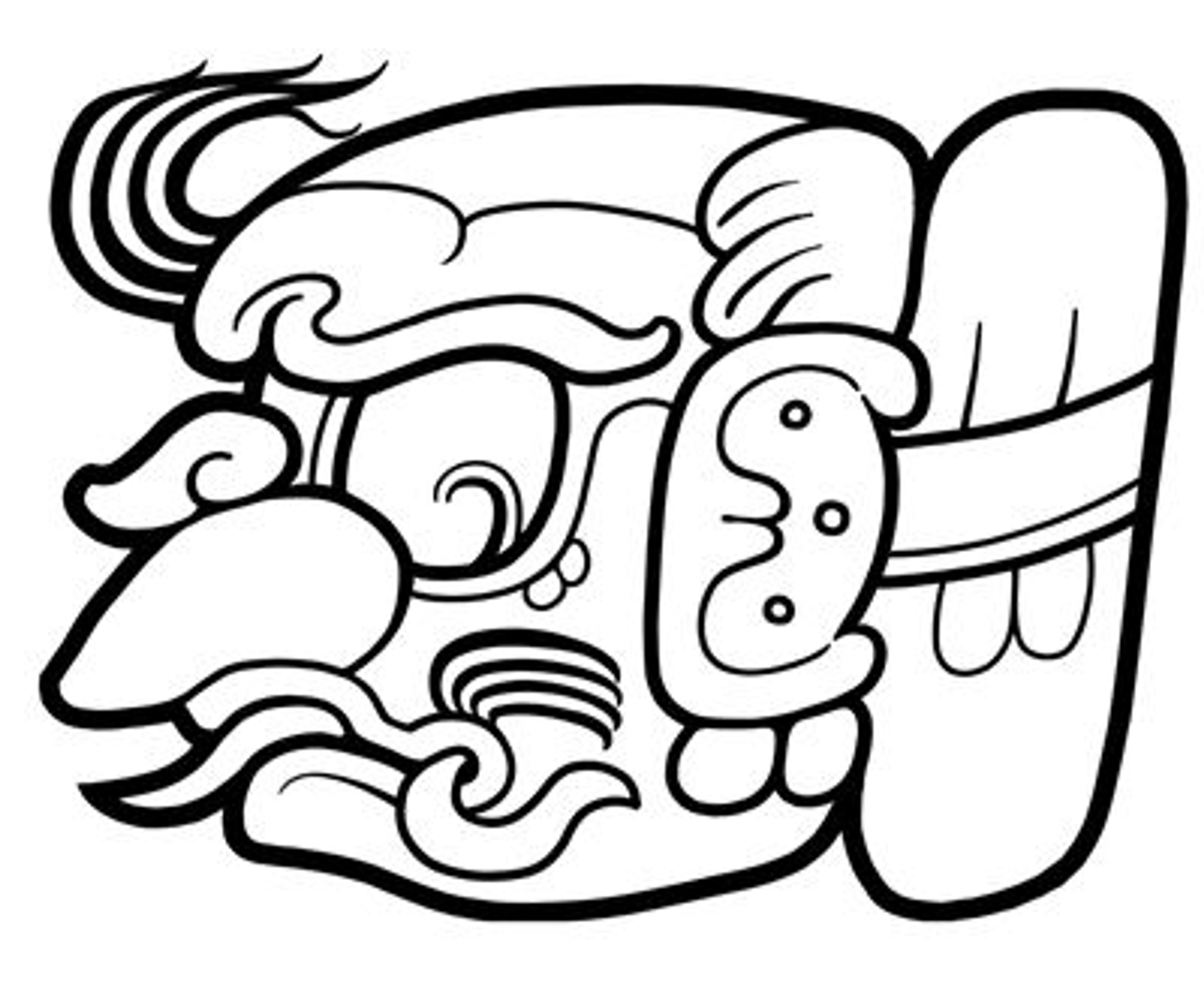

Rain God

The profile-face glyph of the god of rain and storms is normally complemented by the syllable ki, which indicates that the name ends with the sound k. Scribes sometimes rendered it using the syllables cha and ki, which also produce the reading “Chahk.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Maize

Maize is the staple crop of the Maya, and closely associated with ideas of personhood. Narratives from highland Guatemala explain that the gods first attempted to create people from clay and wood, which yielded awkward beings who did not recognize their creators. On their next attempt, the gods made people from maize, successfully forming well-shaped, intelligent humans who could speak and worship their creators appropriately.

The Maize God is an eternally youthful being who endures trials and overcomes the forces of death. Maya artists portrayed him as a graceful young man with glossy skin and a sloping forehead, his elongated head resembling a maize cob crowned with silky, long locks of hair. The epitome of male beauty, this young god was also associated with jade and cacao, two of the most valuable items in ancient Maya economies.

Episodes from the Maize God’s mythical saga appear on some of the finest ceramic vessels known from the ancient Americas. Formally appealing and conceptually rich, the Maize God’s transit through death and his subsequent rebirth were metaphors for regeneration and resilience.

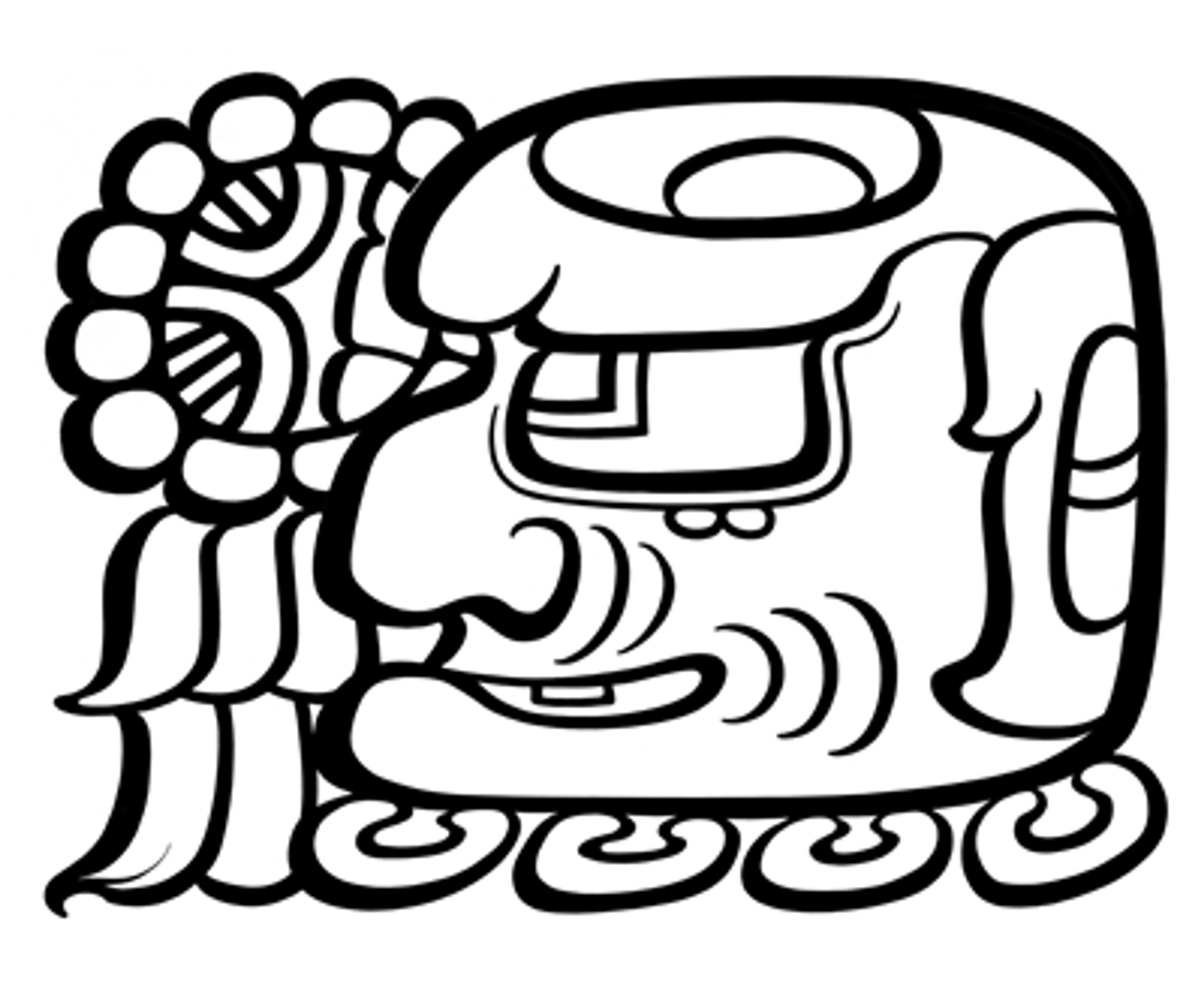

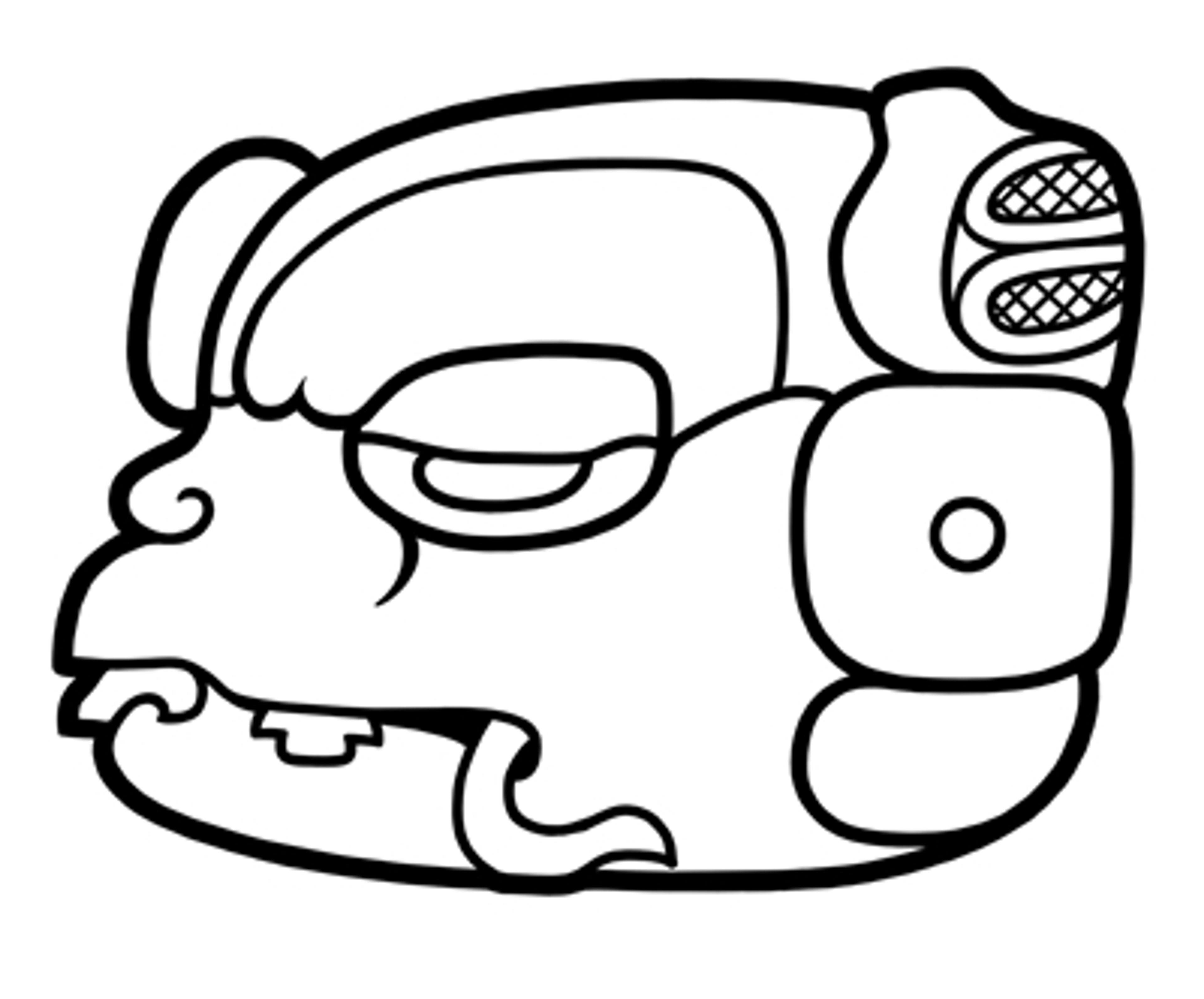

Maize God

The profile of the Maize God—which also stands for his name— possibly reads ixi’m, or “maize.” The glyph is often combined with the numeral one, yielding the reading Juun Ixi’m, “One Maize.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Knowledge

Books made from long strips of folded bark paper were repositories of knowledge about the gods and rituals, the sacred calendar, celestial observations, and predictions for events to come. Scribes who spent long years learning the intricacies of Maya writing employed hundreds of signs in varied combinations. Only four of the books created in the pre-Hispanic period have survived to the present day. Fortunately, texts that remain on relief sculptures and delicately painted ceramics provide a direct source for Classic Maya political history, such as alliances and conquests, and spiritual beliefs. Some of these works include the names of the artists and scribes who made them—the only artists known by name from the ancient Americas.

In the sixteenth century, Maya scribes adopted alphabetic writing introduced by Spanish missionaries, and created accounts of their history and religious beliefs, including a book known as Popol Wuj. Written by the K’iche’ of the western Guatemalan Highlands, this account describes the origin of the world, the former eras, the birth of the sun and the moon, and the discovery of maize. Despite centuries of religious change, many members of modern Maya communities observe the sacred calendar and venerate traditional deities.

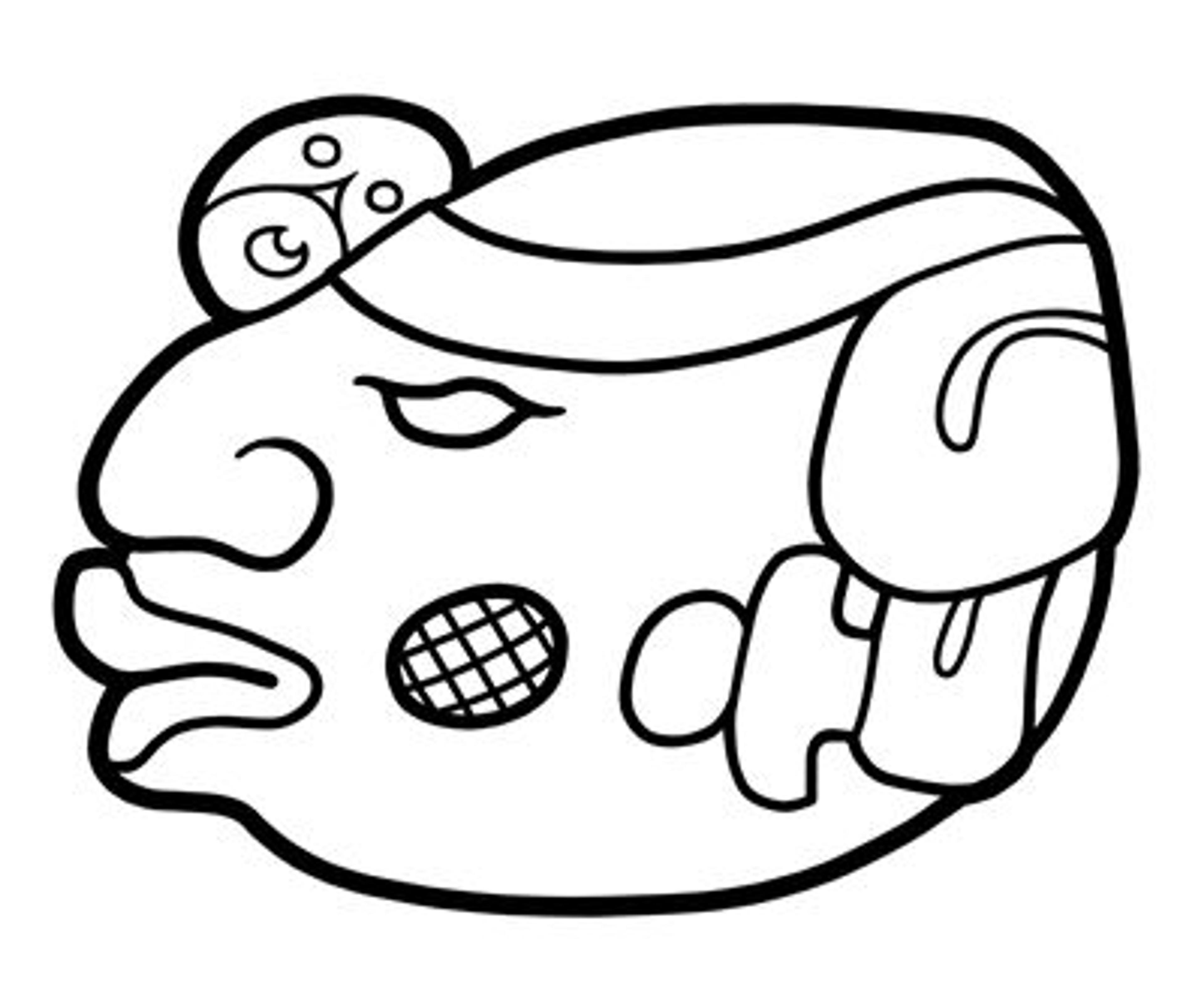

Chuwen

The glyph Chuwen, which corresponds to the name of the patron deity of scribes and artists, portrays a howler monkey—a noisy inhabitant of Maya forests—with the pointed ear of a deer and markings signifying darkness.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Patron Gods

Maya artists created monumental sculptures to celebrate historical events and depict the close ties between rulers and the gods. Freestanding slabs known as stelae stood in the large plazas of Maya cities; others were set on buildings as wall panels, lintels, stairways, or other architectural sculptures. The inscriptions on these sculptures cast monarchs as comparable to the gods of a primordial era, situating their actions in a cosmic time frame and listing the deities who were present at dynastic events such as accession ceremonies, when a new ruler attained the throne. Taking names that referred to aspects of godly power, rulers impersonated gods in ritual events by donning their clothes, masks, and other insignia. Kings and queens were especially keen to commemorate patron gods: local incarnations of major deities associated with ruling dynasties and cities.

Depictions of royal women show them appeasing the gods, sometimes in rituals that involved shedding their blood, in order to conjure successful outcomes in birth and battle. After death, kings and queens were sometimes equated, respectively, with the sun and moon deities. While not considered gods during their lifetimes, rulers were nevertheless believed to have supernatural powers. Some of the sculptures on view in this gallery were created shortly before the ninth-century abandonment of many lowland cities.

Ajaw

The essential component of the sign Ajaw, “king,” was a headband with a jewel on front, which marked regal status. Among several variants, the most common glyph shows the profile face of Juun Pu’w, a young pustulous god, wearing the headband.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.