What do Taylor Swift and Vincent van Gogh have in common? According to art historian Kathryn Calley Galitz’s new book, How to Read Portraits, they are both masters of controlling their image through portraiture. Her reexamination of a deceptively familiar genre explores what portraits can tell us about the artist, the sitter, and ourselves. I spoke to Kathy about this publication—the latest title in The Met’s celebrated How to Read series—and how portraiture remains resonant and relevant to this day.

How to Read Portraits is available at The Met Store and can be previewed on MetPublications

Rachel High: This book is part of a series published regularly by The Met since 2008, but How to Read Portraits is somewhat of a new direction for the How to Read series. Could you explain how your volume carries on the spirit and mission of the series while also serving as a departure?

Kathryn Calley Galitz: How to Read Portraits is the twelfth book in the How to Read series. It is true to the series in that it is meant to be accessible to a broad audience as an introduction to an important aspect of art history, using works in The Met collection to explore the topic.

While previous titles focused on a subject grounded in a specific collection area, time period, or type of art, portraiture invites a cross-cultural and cross-collection reading that sets this book apart from the others in the series.

High: And of course, you have experience in this cross-cultural space with your best-selling book Masterpiece Paintings.

Galitz: I do—thank you! I didn’t realize this was going to become my thing, but it is an unexpected joy. One of the rewards of working at a museum with such a diverse and wide-ranging collection is realizing that no work exists in a vacuum. The works of art are in fact talking with one another across time, place, and culture. A project like this brings those conversations to the fore.

High: A search on The Met’s website for “portrait” returns tens of thousands of results for artworks in our collection, over two thousand of which are currently on view. How did you select the fifty-three Met works of art to feature in this book?

Galitz: As the book’s themes emerged, the goal to present as expansive and inclusive a definition of portraiture as possible helped to determine the selection. It is why you see some unexpected choices mixed in with the more familiar works in the book—I wanted to tell the story of portraiture in all its different forms.

Opening spreads of the publication showing details of Zhang Huan (Chinese, b. 1965). Family Tree, 2001. Nine chromogenic prints, each 21 x 16 1/2 in. (53.3 x 41.9 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Leonard C. Hanna, Class of 1913, Fund; and Francis Bacon, (British [born Ireland], 1909–1992). Three Studies for Self-Portrait, 1979. Oil on canvas, each 14 3/4 x 12 1/2 in. (37.5 x 31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998 (1999.363.1 a–c)

The beauty of this book is that it is thematic. Portraits operate on so many levels; they speak to such fundamental human concerns as status, relationships, and identity. The works in one thematic section could be easily placed in another to make different points.

I hope the book empowers readers to think of these timeless preoccupations and use them to interpret the works that they see beyond this book and The Met; that they understand how portraits are part of a universal, ongoing, and connected conversation.

Opening spreads of the publication showing details of Seydou Keïta (Malian, ca. 1921–2001). Untitled, #313 (Woman Seated on Chair), 1956–57. Gelatin silver print, 2001, image 22 x 15 1/2 in. (55.9 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph and Ceil Mazer Foundation Inc. Gift, 2002 (2002.217); and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749–1803). Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carraux de Rosemond (1765–1788), 1785. Oil on canvas, 83 x 59 1/2 in. (210.8 x 151.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Julia A. Berwind, 1953 (53.225.5)

High: That gets at the core of the mission of the How to Read books; they are meant to give you a framework for thinking about art. One element that sets this book apart from other titles in the series is that it begins with a suite of portraits across time, cultures, and techniques. Could you speak about these images, especially the pairings, and how they help introduce your text?

Galitz: A lot of the credit goes to the book designer, Rita Jules. When we first spoke about the book, I emphasized the dialogues between and among the works of art in my text, and she had the vision to represent these exchanges in a picture gallery of paired images that introduce the book. Before there's even any text, you have these intimate, up-close-and-personal encounters with different faces in different media from various cultures and time periods. The pairings are visually compelling. They are not meant to suggest that one artist saw work by the other, but they create unexpected conversations and set the stage for the sheer breadth of the book.

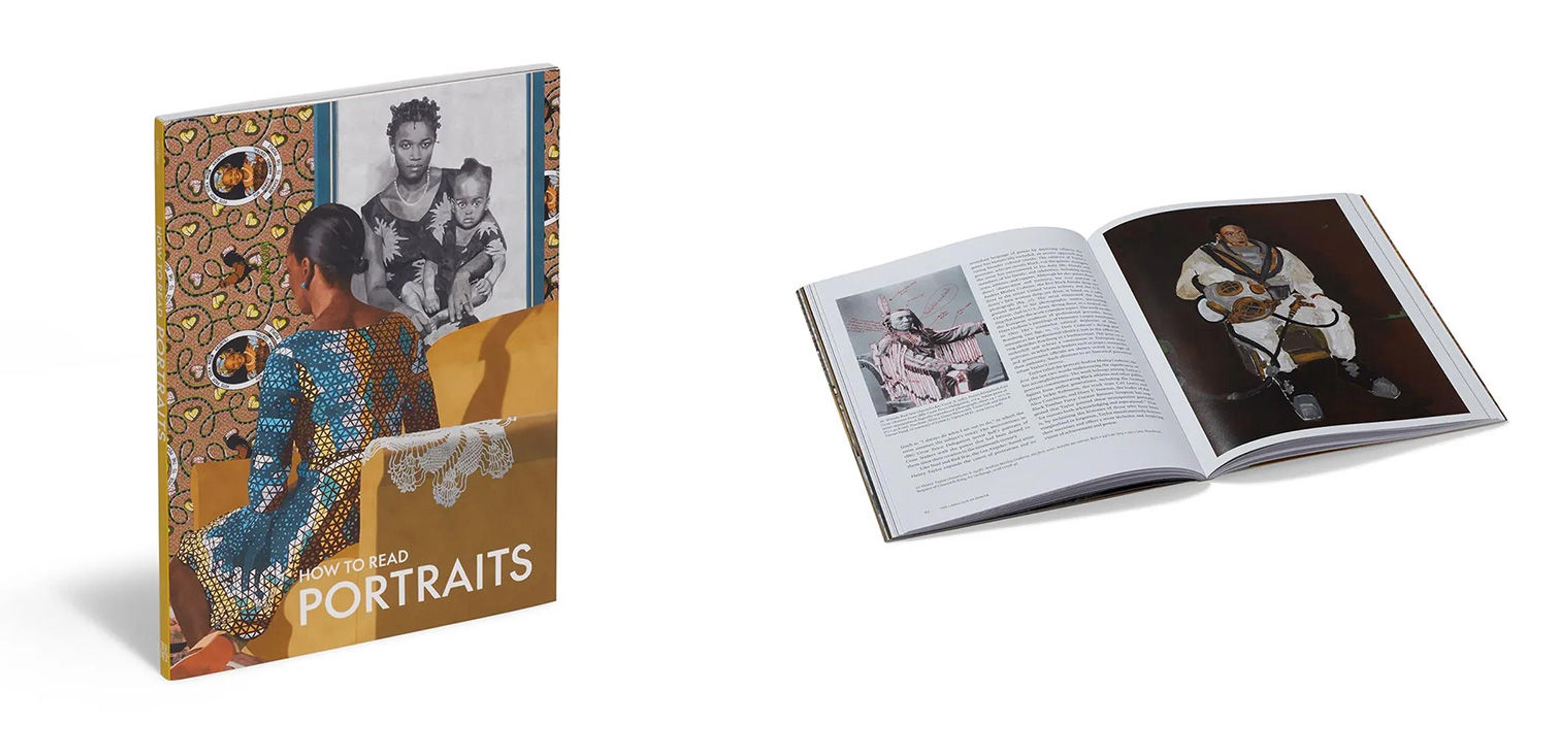

High: It is hard to capture the extent of this publication in just one or two images. Could you speak about the choice of images for front and back cover?

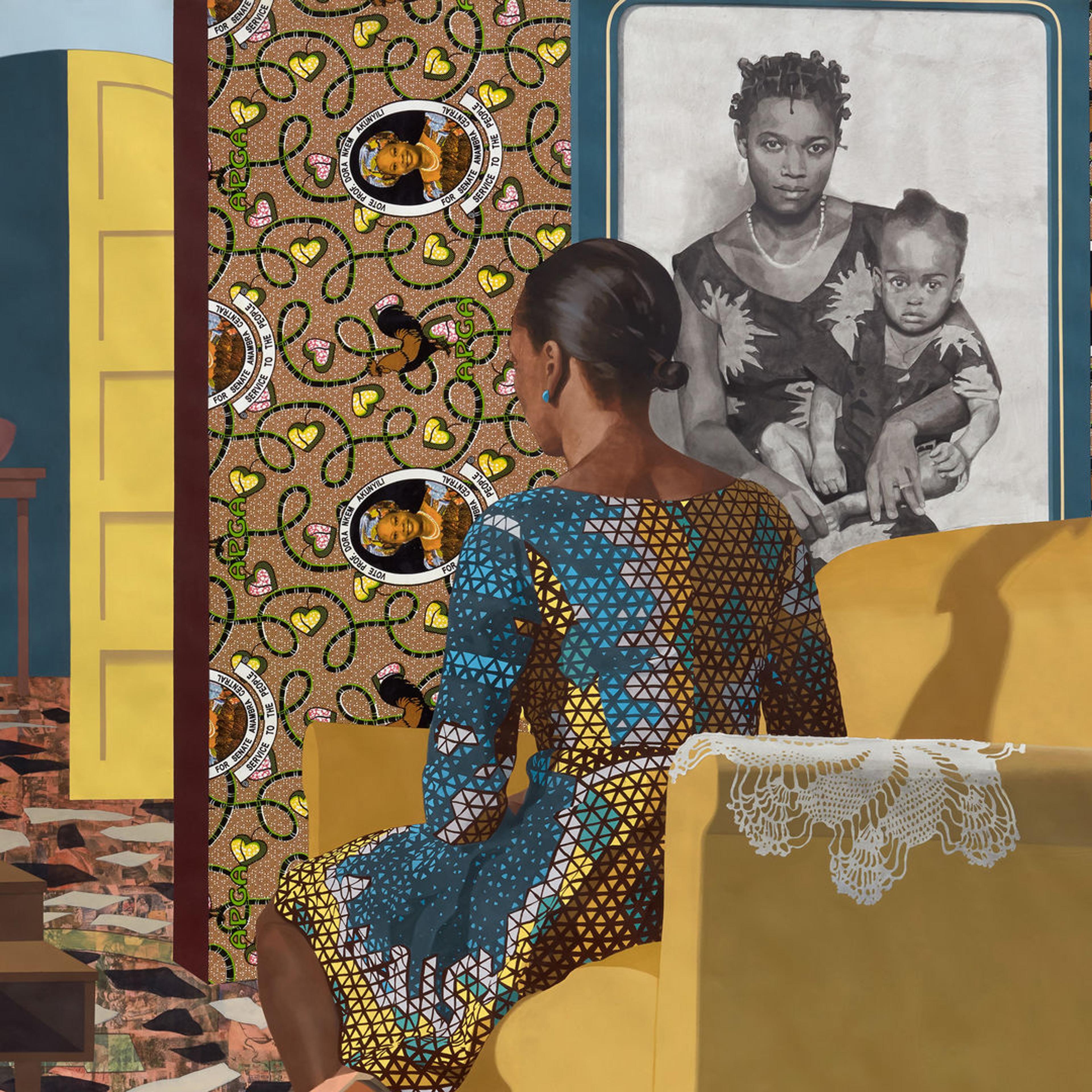

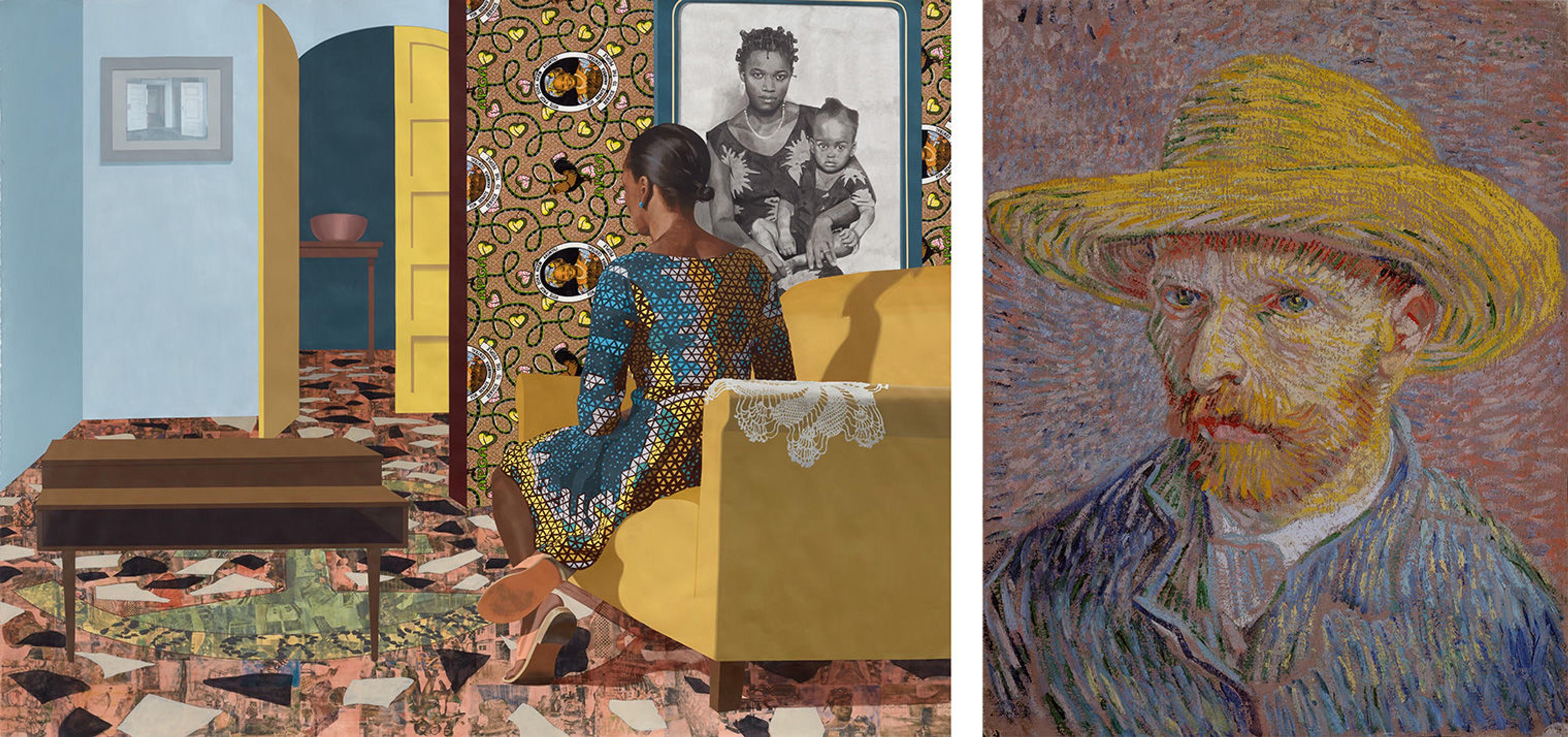

Left: Njideka Akunyili Crosby (Nigerian, b. 1983). Mother and Child, 2016. Acrylic, transfer printing, colored pencil, cut and pasted paper, and printed fabric on paper, 95 3/4 in. x 10 ft. 4 1/4 in. (243.2 x 315.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation Gift, 2017 (2017.106). © Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Right: Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat, 1887. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 1/2 in. (40.6 x 31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), 1967 (67.187.70a)

Galitz: For the front cover, we chose Mother and Child, a work painted in 2016 by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and we put one of our iconic portraits, Vincent van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (1887), on the back cover. Our choice to put a work made within the last ten years on the front cover of this book signals this volume’s contemporary relevance.

The multi-layered aspect of Mother and Child encapsulates much of what this book is about. The sitter—who is, in fact, the artist—has her back turned to us. The work is a self-portrait, but embedded in it are other portraits that invite us to deconstruct its meaning.

In the book, I explain that Akunyili Crosby’s work is intrinsically bound up with her dual identities as a Nigerian and an American. She came to the United States from Nigeria at the age of sixteen to pursue her education; she speaks of herself as someone from “multiple worlds.” She also plays with other meanings, including notions of public and private. In her work, the boundaries between public and private lives blur. Though Mother and Child seems very private and inward-looking, it was painted as a public work meant to be seen and exhibited.

By contrast, Van Gogh's Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat, which is so familiar to us today and seen by millions of visitors every year, was actually an experimental, intimate painting that Van Gogh used to hone his skills as a portraitist. He couldn’t afford to pay for models, so he bought a mirror and served as his own model, variously experimenting with technique and format.

These two very different approaches to self-portraiture show how artists have deployed the genre to very different ends, both stylistically and expressively.

High: These notions of public and private recur throughout your text. Another thread is that of a portrait as a likeness—faithful or unfaithful though it may be. How can likeness (or deviations from likeness) imbue meaning or achieve certain goals of the sitter or artist?

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641). James Stuart (1612–1655), Duke of Richmond and Lennox, ca. 1633–35. Oil on canvas, 85 x 50 1/4 in. (215.9 x 127.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889 (89.15.16)

Galitz: At a basic level, a portrait is understood as a record of an individual’s appearance. Likeness has long dominated the discourse on portraiture. In the seventeenth century, Anthony van Dyck was renowned for his ability to make his royal and aristocratic sitters look like a better version of themselves. Beyond flattering likenesses, Van Dyck mastered the language of pose and setting to express his sitters’ status and authority.

Nigeria, Igun-Eronmwen guild, Court of Benin. Edo. Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century. Ivory, iron, and copper, 9 3/8 x 5 x 2 1/2 in. (23.8 x 12.7 x 6.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972 (1978.412.323)

There was great appeal to this perfected version of the self, and that’s not unique to Western art. We see it in stylized African masks like the Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba from the sixteenth century. Her portrait, while individualized, is idealized, as reflected in the serene expression and perfect symmetry of the features. The desire to look our best transcends time and place. Following this current within portraiture, you realize that when artists created idealized versions of their subjects, they were already playing with notions of likeness and even beginning to subvert them.

With the invention of photography in the nineteenth century, many thought it was the death knell of portraiture—fearing that once someone’s likeness could be mechanically reproduced there would be no point in conveying it in any other media. This was, of course, a very narrow definition of portraiture. In my book, I raise the question: is likeness a prerequisite for a portrait?

Publisher and Editor in Chief Mark Polizzotti encouraged me to pursue an expansive approach to portraiture. Symbolic portraits, which abandon likeness, are just one example. Maybe this is getting a bit Proustian, but the senses are intrinsically tied to memory. Just seeing an object can connote a particular person or a part of someone can represent the whole.

A traditional lover’s eye. Edward Greene Malbone (American, 1777–1807). Eye of Maria Miles Heyward, ca. 1802. Watercolor on ivory, 3/8 in. (1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dale T. Johnson Fund, 2009 (2009.243)

Here, I’m thinking of a wonderful tradition of miniatures first popularized in eighteenth-century Europe known as “lover’s eyes.” These small works were literally just that: they showed a single eye or a pair of eyes of a beloved individual. They were worn as a locket, brooch, or could be carried in a small box close to the body. Only the subject, the recipient, and the artist of that miniature knew whose eyes were portrayed. There’s an unconventional variation on the “lover’s eye” miniature in the book that I'll leave as a surprise.

High: Speaking of lovers, “Swifties” will be delighted to come across a familiar face when flipping through the book. How do you explore the relevance of portraiture to contemporary popular culture in your text?

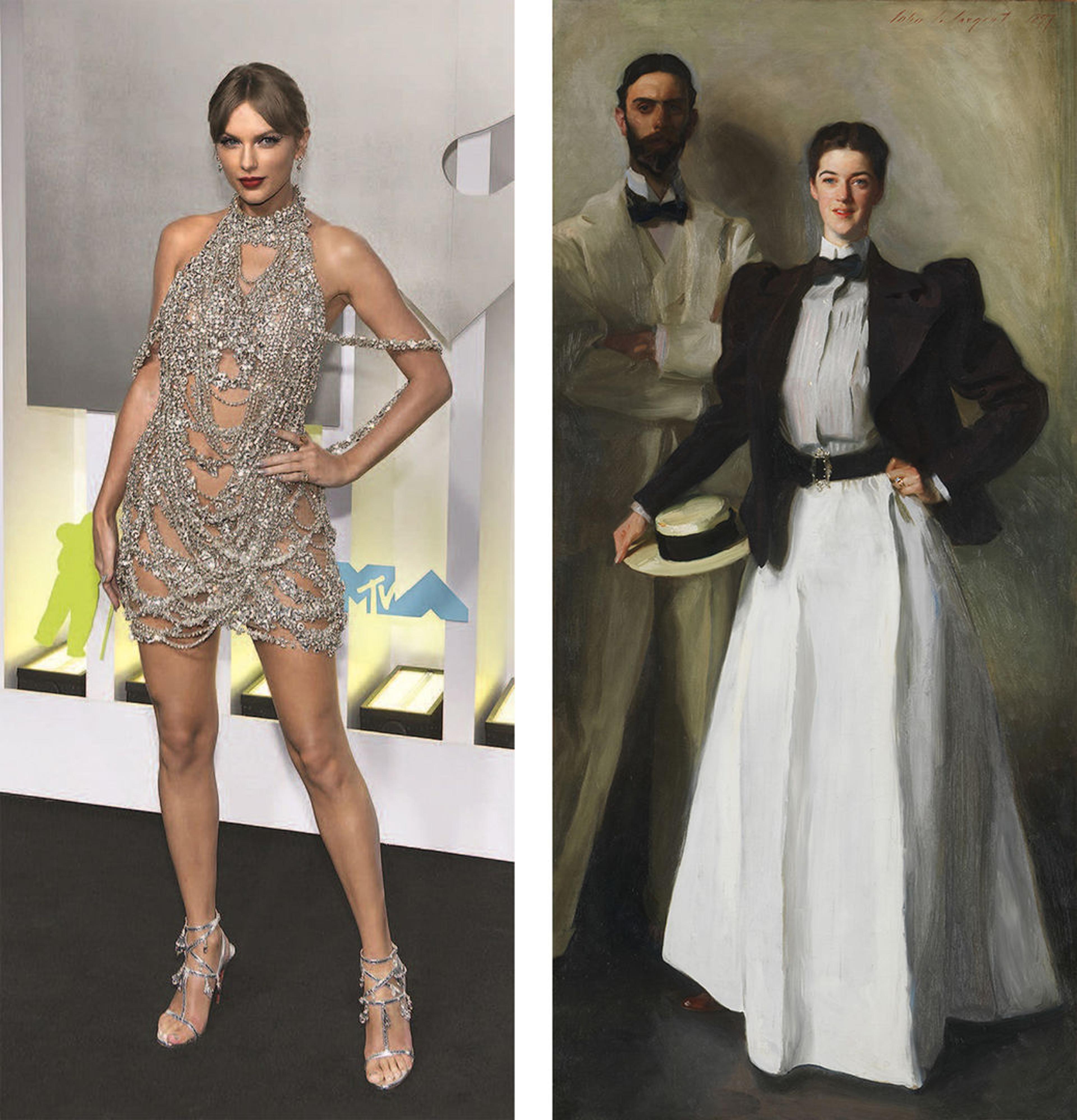

Galitz: Today, most of us encounter portraits in our daily lives on social media, such as the ubiquitous images of celebrities posing on the red carpet. The poses they strike and what they are wearing contribute to their image. This is no different than the function of a portrait hundreds of years ago, although the power of portraits today is arguably even more immediate and impactful because they can be instantly disseminated around the world to millions of people. The image in the book you’re alluding to shows Taylor Swift in what has become her go-to pose: hand-on-hip with a slight weight shift.

Left: Taylor Swift at an awards show, 2022. Photo by Jeremy Smith/imageSPACE/Sipa USA (Sipa via AP Images). Right: John Singer Sargent (American [born Italy] 1856–1925). Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, 1897. Oil on canvas, 84 1/4 x 39 3/4 in. (214 x 101 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Edith Minturn Phelps Stokes (Mrs. I. N.), 1938 (38.104)

This pose recurs throughout the history of portraiture. It is associated with power, authority, and confidence. Significantly, the hand-on-hip pose was popularized in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as a symbol of male authority and was thought to convey a certain amount of assertiveness and even aggression that was not in keeping with how it was thought that a woman should behave in polite society.

By the turn of the twentieth century, John Singer Sargent was painting portraits of women shown with their hands on their hips; assuming this traditionally male pose was a significant departure from artistic convention and statement-making in itself. Taylor Swift is using the same pose to empower herself and countless other young women and girls to feel that same kind of ownership over their images.

This ties into another idea running throughout the book: celebrity. We might think that celebrity is a recent phenomenon, but the modern concept of celebrity dates back to the eighteenth century with the rise of popular prints, newspapers, and public exhibitions in England and France. Artists gravitated toward people in the news so they could piggyback on the fame of their subject.

For example, John Singer Sargent painted Madame Pierre Gautreau—better known as Madame X— a public figure in 1880s Paris. He was an American trying to make a name for himself in the city and get future commissions. It made sense for him to paint this renowned beauty. It was mutually beneficial. Portraits are a negotiation between artist and sitter; there's agency on both sides.

At least that’s usually true. With the rise of the caricature in eighteenth-century Europe, artists made what were often politicized images rooted in likeness but taken to the extreme. They reduced public figures to their most salient physical characteristics. Napoleon Bonaparte, for example, was, and still is, recognized by his short stature and his bicorne hat, always sported sideways.

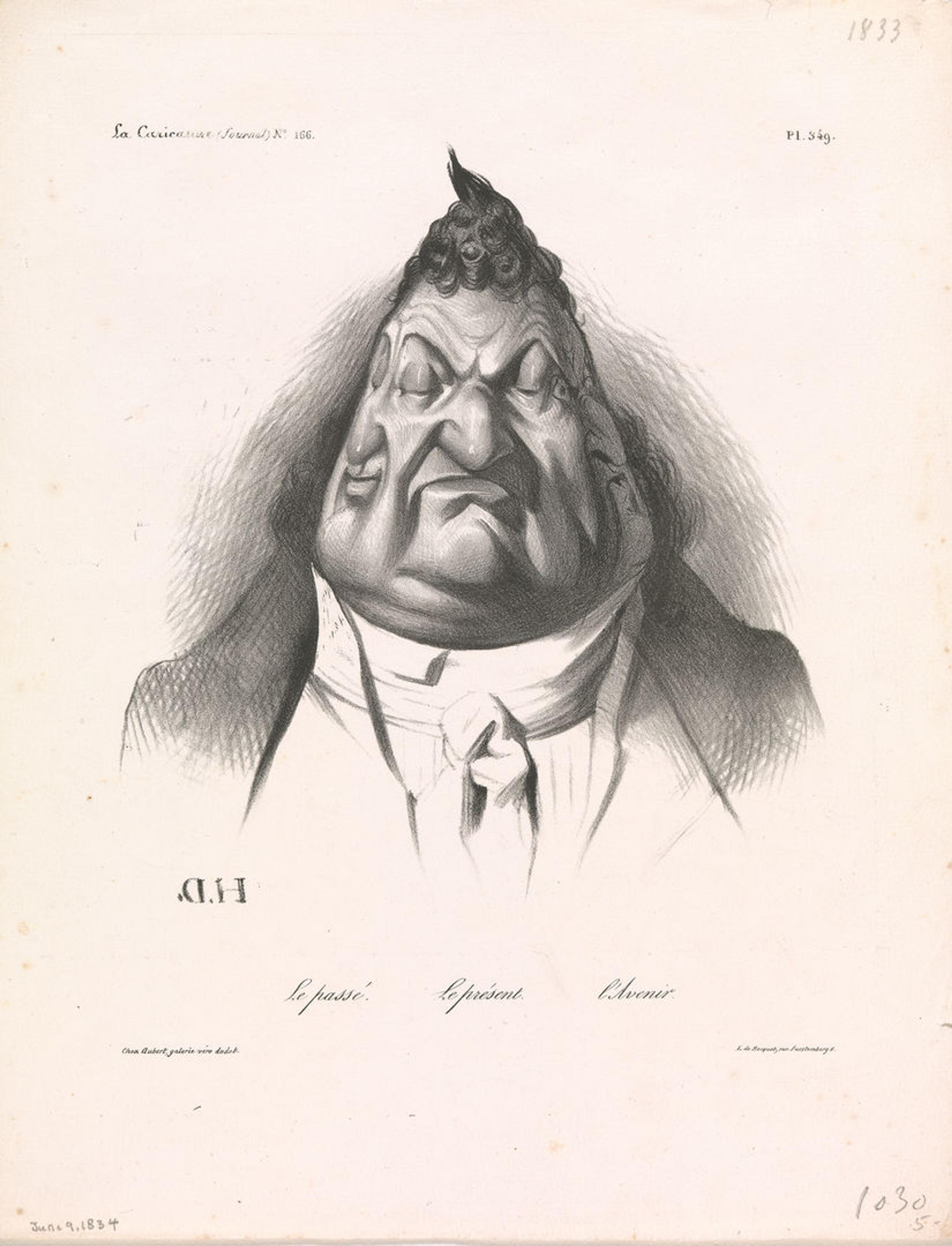

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808–1879). The Past, the Present, and the Future (Le passé – Le présent – L'Avenir), published in La Caricature, no. 166, Jan. 9, 1834, 1834. Lithograph, 13 3/4 x 10 5/8 in. (35 x 27 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1941 (41.16.1)

King Louis Philippe of France, who from 1830 to 1848 ruled the July Monarchy, was known for leading a corrupt regime. He had a distinctive, pear-shaped head. The artist Honoré Daumier picked up on this in his biting caricatures of Louis Philippe, including one with a three-faced head that shows the progressive “rotting” of his regime, like an overripened fruit. An image of a pear came to serve as a stand-in for the king. The government eventually censored these caricatures, which shows how powerful portraiture can be, and certainly, power has been a key driver of portraiture since its origins.

High: Many people do not think of caricatures when they think of portraits, and readers might be surprised to find some examples of portraiture in the book that are not generally associated with fine art. Could you speak about the inclusion of objects like the Honus Wagner baseball card?

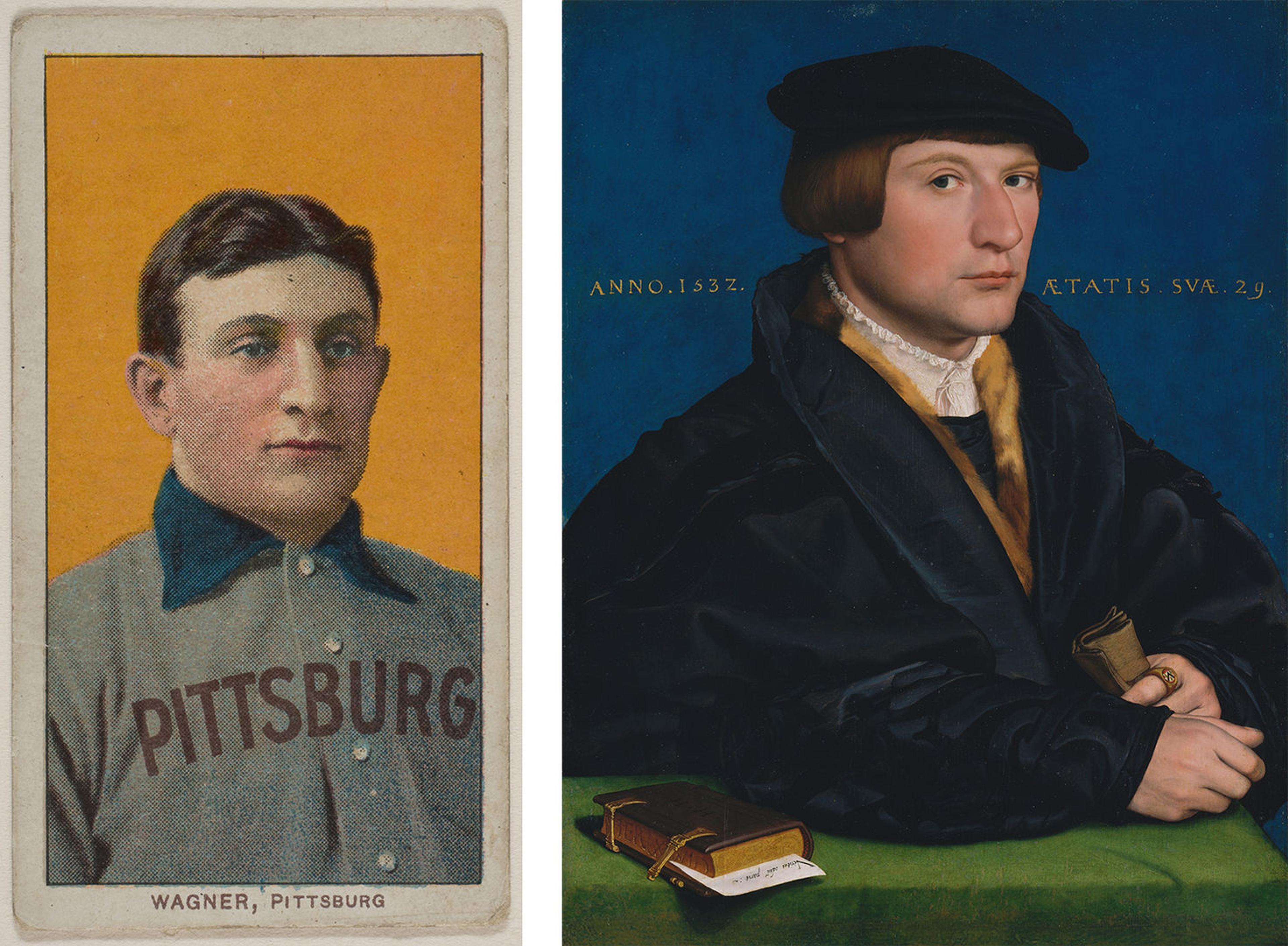

Left: Honus Wagner, Pittsburgh, National League, from the White Border series (T206) for the American Tobacco Company, 1909–11. Commercial lithograph, 2 5/8 x 1 1/2 in. (6.7 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.246.206.378). Right: Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497/98–1543). Hermann von Wedigh III (died 1560), 1532. Oil and gold on oak, 16 5/8 x 12 3/4 in. (42.2 x 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Edward S. Harkness, 1940 (50.135.4)

Galitz: I was struck by the fact that Honus Wagner’s image is a traditional bust-length portrait not unlike one of Hans Holbein’s sixteenth-century portraits.

The rise of professional sports in the late nineteenth century created a demand for images of popular baseball players. At first, these images were distributed with tobacco, but in consideration of younger sports fans, the cards were sold with packs of bubble gum beginning in the 1930s.

The Honus Wagner card featured in the book was distributed from 1909 to 1911 when the cards were still sold with tobacco. It is such a rare card because Wagner demanded that the manufacturers stop production. The story is that he objected to his image being used to sell tobacco to children, but some argue that he merely wanted to get a cut of the profits, so whether he truly had young Americans interests at heart remains to be seen.

High: Fascinating. And as you mention in the book, collectible portraits go back as far as Roman times when prominent individuals were featured on coins or cameos.

Galitz: Absolutely. Today anyone with a camera on their phone can make a self-portrait and distribute it. While the much-derided selfie is a pop-culture phenomenon, it is rooted in the tradition of self-portraiture. Access to new technology plays a role in art, too; the rise of self-portraiture in the late fifteenth century coincided with the wider availability of quality mirrors.

And, of course, identity is intrinsic to portraiture, from selfies to more formal portraits—they reveal how you see yourself and how you want others to see you. I think a heightened awareness of identity has contributed to the resurgence of portraiture in recent decades by artists like Titus Kaphar, Aliza Nisenbaum, Catherine Opie, and Amy Sherald, who portray subjects whose identities haven’t been represented in traditional portraiture or have been marginalized at best. Part of why I'm so drawn to the genre is because it's not static; it's fluid, evolving, constantly changing, and responding to the world in which we live. This is what makes portraiture so exciting.