The celebrated painter Jacob Lawrence was fifty-one when Carroll Greene interviewed him for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art’s oral history project in the fall of 1968. An edited and abridged version of their illuminating conversations appears below, published on the occasion of Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, an exhibition featuring the artist’s little-seen multi-paneled series, “Struggle: From the History of the American People” (1954–56).

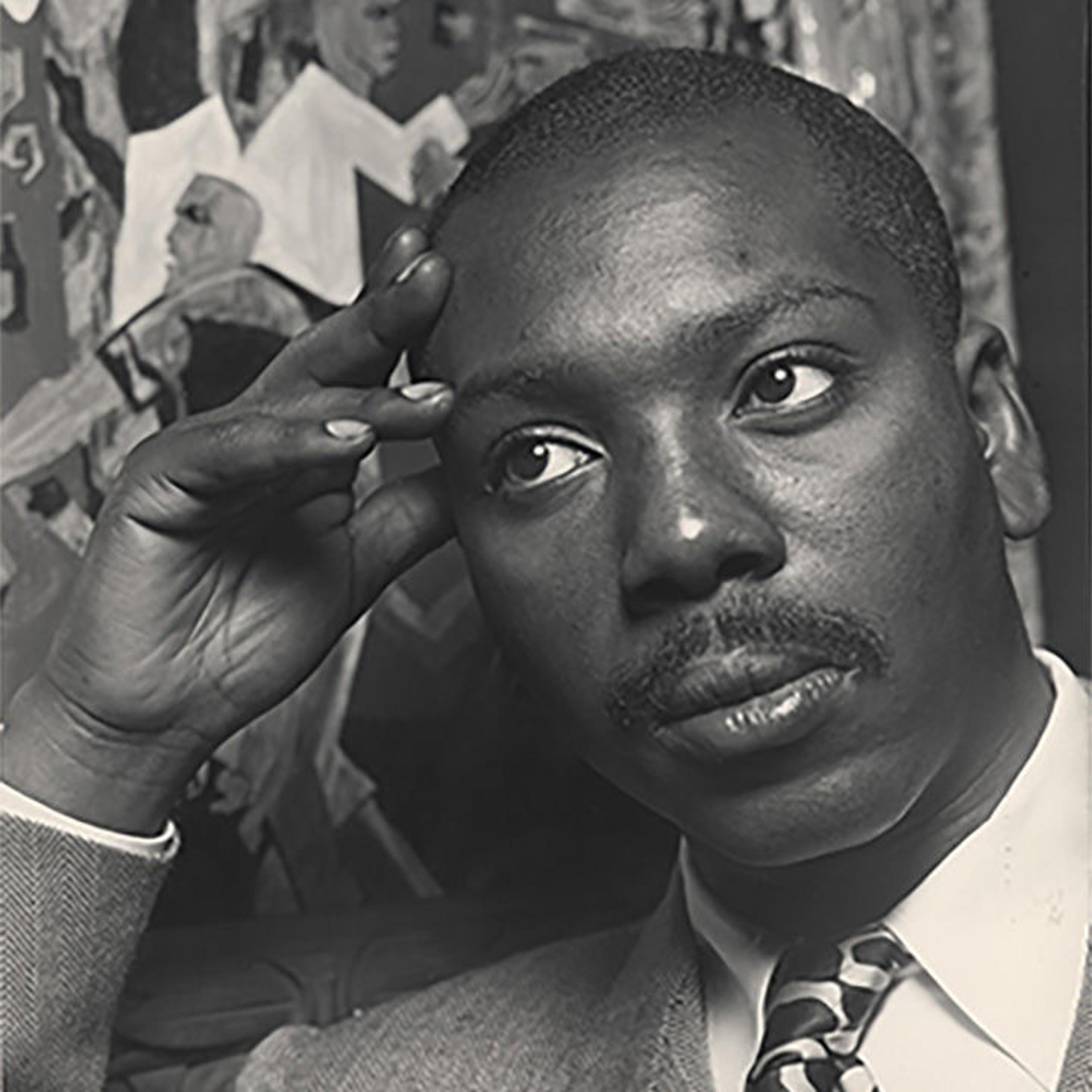

Lawrence was one of the first African American artists to gain broad recognition within the segregated art world of the 1940s, and he is renowned for his serialized projects, including “The Migration of the Negro” (1940–41) and “War Series” (1946–47), among other works. While The Met neglected so many talented artists of color throughout the twentieth century, the Museum was an early collector of Lawrence’s work, having acquired Pool Parlor in 1942, a gouache on paper that depicts a bustling Harlem bar.

Left: Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Pool Parlor, 1942. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 31 1/8 x 22 7/8 in. (79.1 x 58.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1942 (42.167). © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Blind Beggars, 1938. Tempera on illustration board, 20 1/8 x 15 in. (51.1 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (43.47.28). © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lawrence produced “Struggle” in the mid-1950s—the heyday of abstract painting in the United States—and, likely as a result of its figurative style and historical focus, the series was eclipsed at the time. It is also among the least known of his series due to the fact the paintings were separated at an early date, against the wishes of the artist and his dealer. The current exhibition represents the first time the existing “Struggle” panels have been reunited in more than sixty years, giving viewers the opportunity to understand the prescient power of Lawrence’s reckoning with America’s revolutionary past.

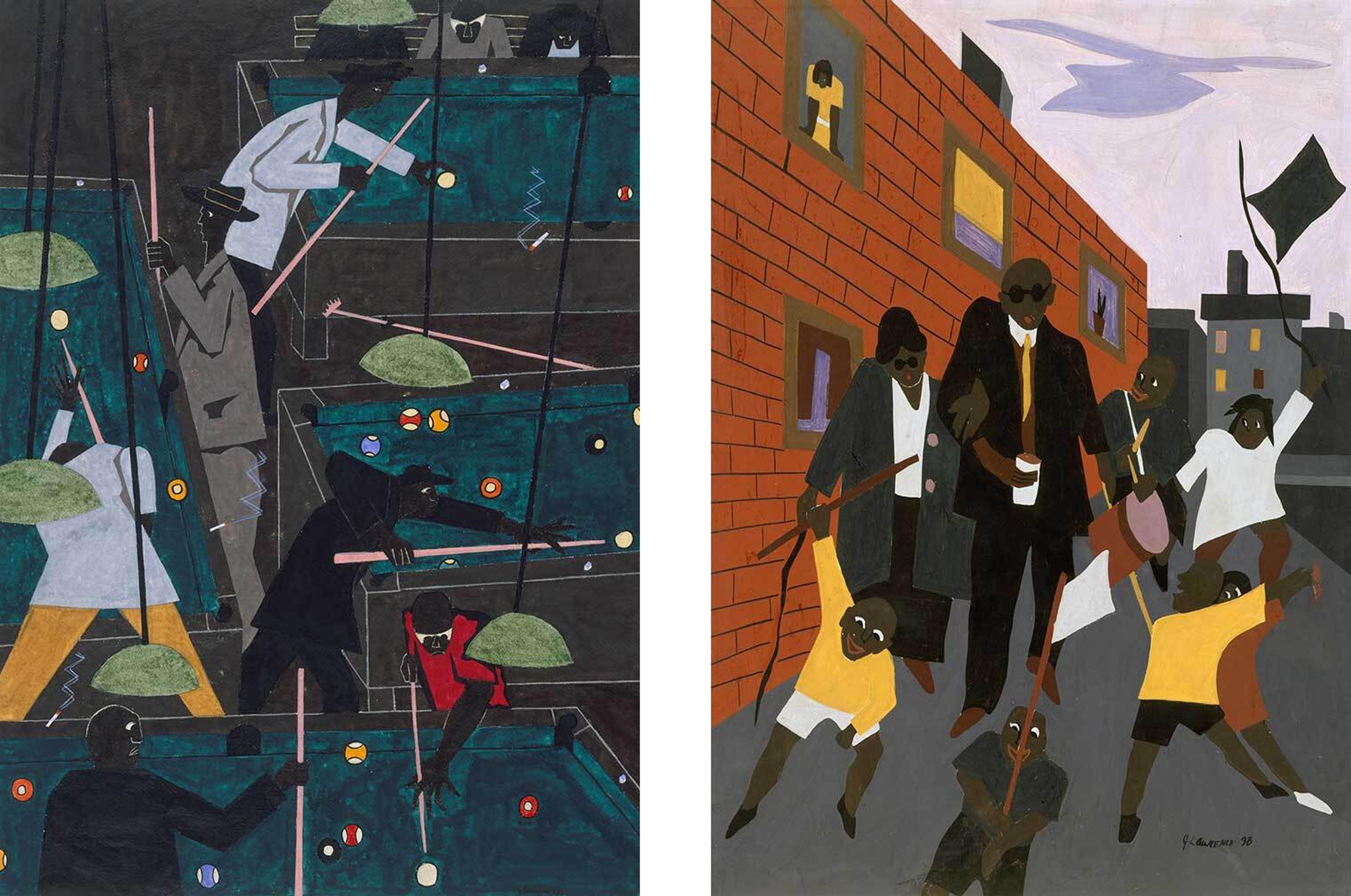

Across thirty panels, the artist depicts iconic and lesser-known episodes from the country’s founding decades, focusing on themes of rebellion, emancipation, and westward expansion. By foregrounding the stories of women and people of color in these pivotal moments, he counters the celebratory Eurocentric and masculine narratives of mainstream American history prevalent in the Cold War years. For example, in And a Woman Mans a Cannon, Lawrence depicts Margaret Cochran Corbin and her critical role in the Battle of Fort Washington, in what is now upper Manhattan.

Today, twenty-five of the thirty panels in the “Struggle” series are held in known public and private collections; the other five are unlocated. The Met owns one panel from the series, We crossed the River at McKonkey’s Ferry 9 miles above Trenton …, a riveting counterpoint to Emanuel Leutze’s iconic Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), housed in the Museum’s American Wing. Lawrence’s rendering of this epic subject emphasizes the anonymous soldiers who accompanied Washington, rather than portraying the general as the sole heroic figure.

Flanking the entrance to Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle are works on paper from earlier periods of Lawrence’s career.

When Carroll Greene interviewed Lawrence in 1968 for the dialogues excerpted below, he had just begun a formative fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution; Greene would go on to become an influential historian of African American art. Lawrence, who taught that tumultuous year at the celebrated Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, also participated in The Met’s landmark symposium “The Black Artist in America.”

The symposium was a prelude to The Met’s now-infamous 1969 exhibition Harlem On My Mind. While the show claimed to survey life in Harlem since 1900, it failed to include any actual works of art—it was composed almost entirely of photographic reproductions depicting the creative capital of Black America. Harlem On My Mind was boycotted by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), a group of artists who protested The Met and other New York museums for failing to adequately represent African American artists in permanent collections and programming. Similar concerns have been articulated recently by activist groups like the Movement for Black Lives, as museums continue to reckon with institutional legacies of white supremacy.

Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle is on view at The Met through November 1, 2020.

Installation view of The American Struggle

Jacob Lawrence:

When I tell people that I was born in Atlantic City I always have to follow that up with, “But I know nothing about it.” My parents were part of this Negro migration which took place right after World War I, coming north to seek work. They were domestics.

So my experience with Atlantic City was almost nothing. And then my parents moved to Easton, Pennsylvania, which was I think a coal-mining town. My mother and father separated about that time, and my mother took us to Philadelphia. We stayed there for a few years. I remember settlement houses, and I think my mother had quite a hard time because she had no one to help her support us. And finally she came to New York, where I’ve been ever since.

Carroll Greene:

You’ve been in New York City since 1933?

Lawrence:

The Crash was 1929. It must have been a couple of years after that. It must have been about 1931. We came to New York and of course this was a completely new visual experience, seeing the big apartments. When I say “big” I mean something six stories high because I wasn’t used to apartment houses.

And what I did miss coming here was the playing in open lots. In Philadelphia you had open lots where we used to play marbles and things like that, and you didn’t have to worry about vehicular traffic. I did miss that. Here they were confined to just shooting marbles in the gutter and that type of thing. This move was quite an experience for me.

And of course I was becoming very much involved in art at that time. My first exposure to art—which I didn’t realize was even art—was at an after-school settlement house. It was the Utopia Children’s Settlement House in Harlem.

Greene:

What was your attitude toward Striver’s Row?[1]

Lawrence:

At that time I didn’t have any attitude. You see, my interests were so involved in art but not in a scholarly manner. It was something I just liked to do. I never saw an art gallery until I was about eighteen years of age, which is very unusual for kids who have art in their homes and that type of thing.

My mother was working and she sent us to this after-school place. You’d be there a couple of hours after school. And during that period you participated in whatever the settlement had to offer, which was arts and crafts. I was exposed to soap-carving, leatherwork, woodwork, and painting.

And about this period … we all know this history. The country, of course, was in an economic depression. This is when [Franklin Delano] Roosevelt came in. He started all these relief programs, and they set up these various centers throughout the country.

Greene:

This is the first wave of Black consciousness in America.

Lawrence:

In a cultural way, yes. At this time, my contacts were professional artists much older than myself—people like Augusta Savage. She was the professional person in that area at the time, in the Harlem area. And I think countrywide she was known throughout the Negro communities and probably throughout the American communities when you spoke of the Negro artists.

And then there was Aaron Douglas, of course. And I think Hale Woodruff may have been a little younger than they, but he was also known. Hale Woodruff, Augusta Savage, Richmond Barthe, Archibald Motley, Claude McKay the writer and poet.

The people of the renaissance—I didn’t know them unless they were still living and still living in the Harlem area. The people I came in contact with were people like Charles Alston, like Henry Bannarn, the sculptor. I think these were the earliest influences.

Left: Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). And a Woman Mans a Cannon, 1955. Egg tempera on hardboard, 16 x 12 in. (40.6 x 30.5 cm). Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886–1957). Emiliano Zapata and His Horse (detail), 1932. Lithograph, 16 1/4 x 13 1/8 in. (41.2 x 33.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.26.7). © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Greene:

How did the contact manifest itself? Did you have conversations with these people?

Lawrence:

Well, I went to their schools. You see, all of these people were finally workers on these various projects which were implemented at the time. They were people in college or just coming out of college and so they received these positions as teachers in the art centers. People were encouraged to come in off the streets and work, and I was one of these. Since I did not have a formal art training, my work almost grew out of the way an unsophisticated person would work—not academically. And they did encourage this.

I think it was a period of this kind of encouragement in art—the country was very social minded. I think the big school then was the Mexican School: [José Clemente] Orozco, [Diego] Rivera, [David Alfaro] Siqueiros. Also we were exposed to people like Käthe Kollwitz, the Polish artist. Many of the Chinese artists who were doing big woodblocks; they were doing peasants and that type of thing. And this permeated all of the arts of that period, with the aid of literature and everything. It was a period when a man did his Native Son.

So I’m really a product of this period. I guess it didn’t take much to influence me, because I was working in this kind of genre, and in any event, I took my scenes from the Harlem community. The Harlem community wasn’t an upper-class community—anything you would do would be involved with social statements, you see.

Now the Harlem Art Workshop, that was where I was first exposed to artists of big names—not meeting them, but through books and things like that because we had books around. I was able to look at these books and see how they worked, what they were doing. And I guess it was a sort of training, too.

Greene:

This took on with you, didn’t it?

Lawrence:

It wasn’t a consciousness on my part. It was just that this was the trend. Just like now, or a few years back, a younger painter would be involved maybe in the Abstract Expressionist type of thing, you see. Although I think this was a much greater and much wider type of thing. I think it had to do with the economic condition of the country—not of the country, but of the world.

Greene:

It was an art which had a social relevance?

Lawrence:

That’s right. And therefore, any youngster involved in that period in art, this was all he would get. This was a natural way for me. The people I knew were involved in this kind of philosophy, you see.

Greene:

Yes. As we say, you were caught up in the spirit of the times.

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). We crossed the River at McKonkey’s Ferry 9 miles above Trenton … the night was excessively severe … which the men bore without the least murmur … —Tench Tilghman, 27 December 1776 / Struggle Series—No. 10: Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1954. Egg tempera on hardboard, 11 13/16 x 15 15/16 in. (30 x 40.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2003 (2003.414). © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One of the very positive aspects of the Federal Art Project is that it brought artists of various ethnic backgrounds together.

Lawrence:

Definitely. It not only brought them together in a social manner, but it was responsible for those who may not have developed as professionally as others to receive the experience. So it was like a very informal schooling. You were able to ask questions of people who had more experience than yourself about technical things in painting. They had lectures. They put out books on painting—technical pamphlets and things.

Greene:

It is rather interesting because these themes that you were working on really came to prominence during the Negro renaissance in the 1920s.

Lawrence:

Yes. Thirties and so on. The Depression really sort of brought it to a halt. And about this time too, the American art community was beginning to give some attention to the Negro artist.

Greene:

So much of your painting, since “The Migration of the Negro” series, has centered around Negro or, as is popular today, Black subject matter, as far as content is concerned. Would you care to comment on that?

Lawrence:

My early beginnings has been the Negro experience, so I think it was natural that I would use this symbol for my expression. As I mentioned before, I was very involved with Negro history at the time. I think my first involvement came about from hearing someone at the Harlem YMCA tell the story of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian liberator who is often referred to as the George Washington of Haiti. And from that I did the “Booker T. Washington” and “Harriet Tubman” series.

Now, all of these dealt with the Negro in a historical sense. At the same time, I was doing contemporary single pieces, things dealing with the contemporary scene, my life in Harlem and so on. And just how I happened to get the idea to do the “Migration,” I don’t know. Except that my parents maybe were part of this. I was a product of it as a child. To me, it was a very dramatic thing—this great trek.

Greene:

Did you do research in order to do this?

Lawrence:

Yes, I did quite a bit of research. I was fortunate in that we had the Schomburg Library, which had become one of my favorite places to go.

Greene:

What is the Schomburg?

Lawrence:

The Schomburg Library is one of the most extensive libraries dealing with Negro history in the world. It was established by Arthur Schomburg, who was a Puerto Rican of African descent. This became a favorite place of mine to go and work and do research. And this is where I think I read many books, Du Bois and many books like this.[2]

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Defeat, 1954. Egg tempera on hardboard, 12 x 16 in. (30.5 x 40.6 cm). Private Collection. © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Greene:

Well then, from your “Migration of the Negro” series, which really catapulted you to national attention, your interest has been one that was grounded in history, particularly the history of the Negro.

Lawrence:

Yes. Well, I think I’ve mentioned before that prior to the “Migration” series, the “Frederick Douglass” and “Toussaint L’Ouverture” were first. And when I went into the service [with] the United States Coast Guard—I was in the service twenty-five months—I came out and did a series on my experiences in the war.

Several years ago I started an American history series,[3] which did not pertain strictly to the Negro theme but I think my reason for doing it had something with the Negro consciousness. I wanted to show how the Negro had participated—and to what degree the Negro had participated—in American history.

In fact I call it the “Struggle.” As late as a few years ago in the 1950s, the Negro had not been included in the general stream of American history. We don’t know the story, how historians have glossed over the Negro’s part as one of the builders of America, how he tilled the fields and picked cotton and helped to build the cities.

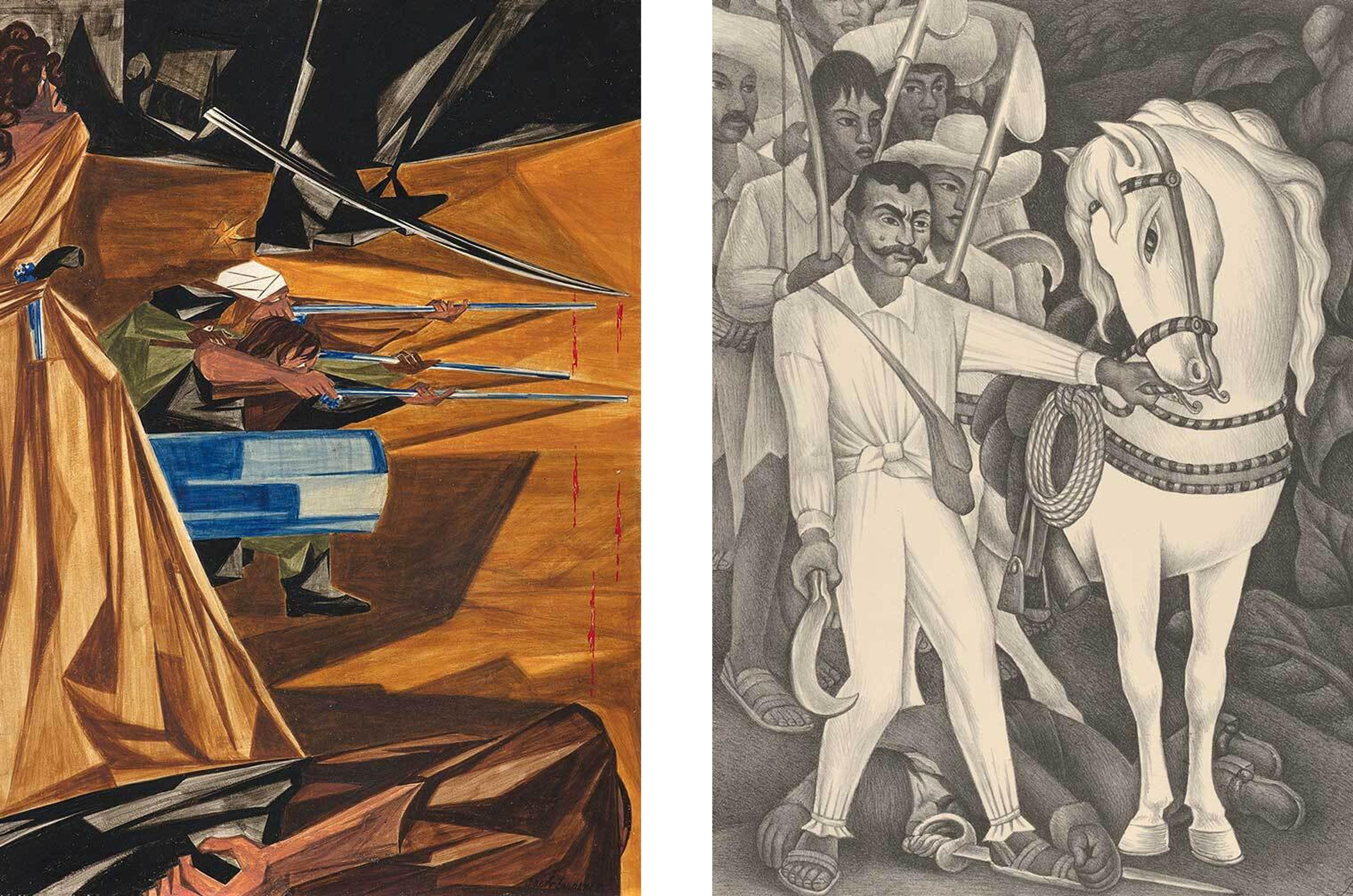

Left: Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). In all of your intercourse with the natives, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit … Jefferson to Lewis & Clark, 1803, 1956. Egg tempera on hardboard 16 x 12 in. (40.6 x 30.5 cm). Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Trappers, 1956. Egg tempera on hardboard 16 x 12 in. (40.6 x 30.5 cm). Collection of Robert Gober and Donald Moffett. © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

But I wanted to do a series showing the American Revolution. Again, this had to do with struggle—the struggle of man. This was not a Negro series; it isn’t just Negroes. It dealt with Negroes who were with Washington when he crossed the Delaware. Not as slaves. These were people who had signed up to take part in the American Revolution.

That’s what’s fascinating about the Schomburg Library. We not only know that Negroes participated in the American Revolution, but we know the names of these people. We can go there and find the actual names of people who enlisted in the American Revolution.

Greene:

I have a feeling that you have an epic sense. It perhaps derives out of your sense of history, a sense of epic proportion. You mentioned Orozco and Rivera and the kind of things which they were doing—the Social Realists and so on.

And thinking back say, on your “Migration of the Negro” series, I was beginning to wonder if you were looking up yourself perhaps as an artist who was in a sense a chronicler of the Black experience in America.

Lawrence:

Yes, this is possible. I’ve been asked this before in various ways. I would say yes, but not consciously on my part. I would rather think that I’m very much interested in the humanistic. Now how this developed, I don’t know. It may have developed because of a lack of formal training at one time. So therefore you work in big forms, which can give your pieces an epic dimension.

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). … is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the prices of chains and slavery? Patrick Henry—1775, 1955. Tempera on hardboard, 12 x 16 in. (30.5 x 40.6 cm). Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2020 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I can well understand what Langston Hughes said before he died that he would never live outside the Negro community. Because this was his life. This was his sustenance. This sustained his motivation and spirit. The importance of contact with artists or people in the arts is part of your education, part of your development. You may not even realize it at the time how important this is.

I think it’s significant that all of this happened in Harlem. When I say “Harlem,” I mean in the broad sense; I don’t mean just the New York Harlem. I imagine this was happening to many people and many Negroes throughout the country in their own Harlems. You see, so many positive things came out of these communities. I know to me it has been a very positive experience. I’ve never left the Negro community in spirit.

The complete transcript of Lawrence and Greene’s dialogue is available at the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art’s oral history program.

Editor’s Notes

[1] Striver’s Row, from 138th Street to 139th Street, Frederick Douglass Boulevard to Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, was home to a number of Black artists, musicians, architects, doctors, and other notable figures in the 1920s. The historic district’s architect, Stanford White, was a partner of McKim, Mead, and White—the same firm that designed The Met’s northern and southern wings in 1926. For its first thirty years, the community was off limits to Black Americans. Return

[2] Today the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is part of the New York Public Library. Return

[3] Lawrence refers here to “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” the series on view at The Met.Return

Marquee: Jacob Lawrence in 1957. Photo (detail) by Alfredo Valente. Image courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art, Alfredo Valente Papers, 1941–78.