Female figurine

Not on view

This female figurine is made of hammered metal sheet and is analogous to other Inca miniature figurines often ritually deposited and considered sacred entities, or huacas, a Quechua and Aymara term. This figurine shows a woman standing with arms and hands pulled toward the chest. Her eyes are almond-shaped and her mouth is closed. As with other figurines in this corpus, the head appears larger than the expected proportion relative to the rest of the body. Of the three height groups (5–7 cm, 13–15 cm, 22–24 cm) evident among this corpus of Inca human figurines in metal, this figurine is in the smallest height group.

This figurine is similar in morphology and fabrication as ones often associated with assemblages from sites of capac hucha, or ‘royal obligation,’ described (Cieza de León 1959, 190–193; Diez de Betanzos 1996, 132) as an Inca state-sanctioned performance. In this practice, offerings were made in Cusco or in the hinterlands to mark the expansion of the empire and the service of the provincial peoples to the Inca royalty, in the process demonstrating reverence to certain sacred points in the natural landscape, including apus, or mountain deities, through the deposition of offerings. This pursuit of territorial control was undertaken through other tactics as well, such as the resettlement of conquered peoples and the mandate that peoples in Inca hinterlands bring huacas to Cusco and care for them there, in the imperial capital (Cobo 1979, 191).

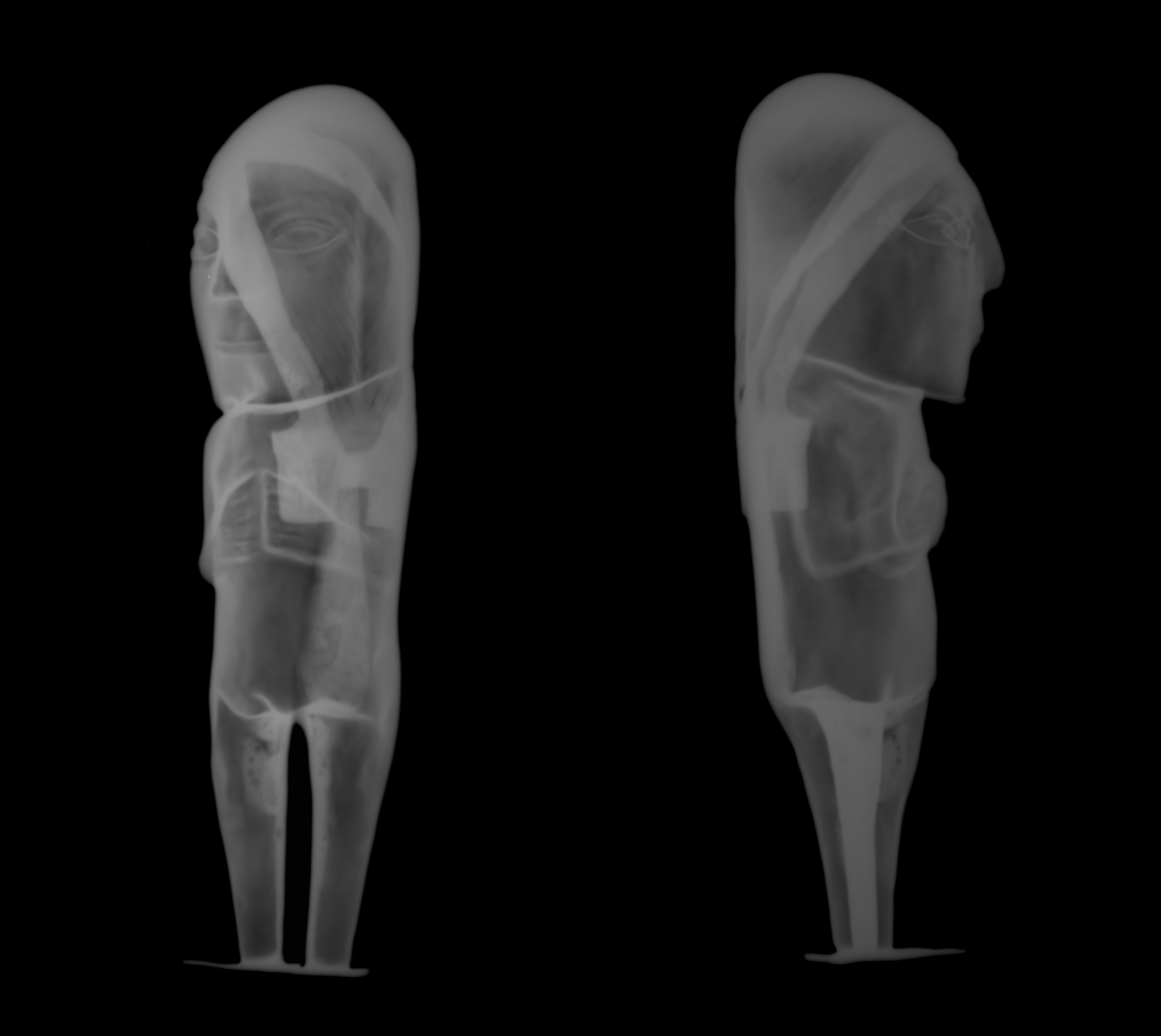

As shown in X-radiography (see image 4), this figurine was fashioned from five separate pieces of sheet: its hair; its head, torso, and legs forming a single piece; the two feet; and a gusset of metal that forms the crotch. The technical design and the arrangement of parts is common to many Inca female figurines.

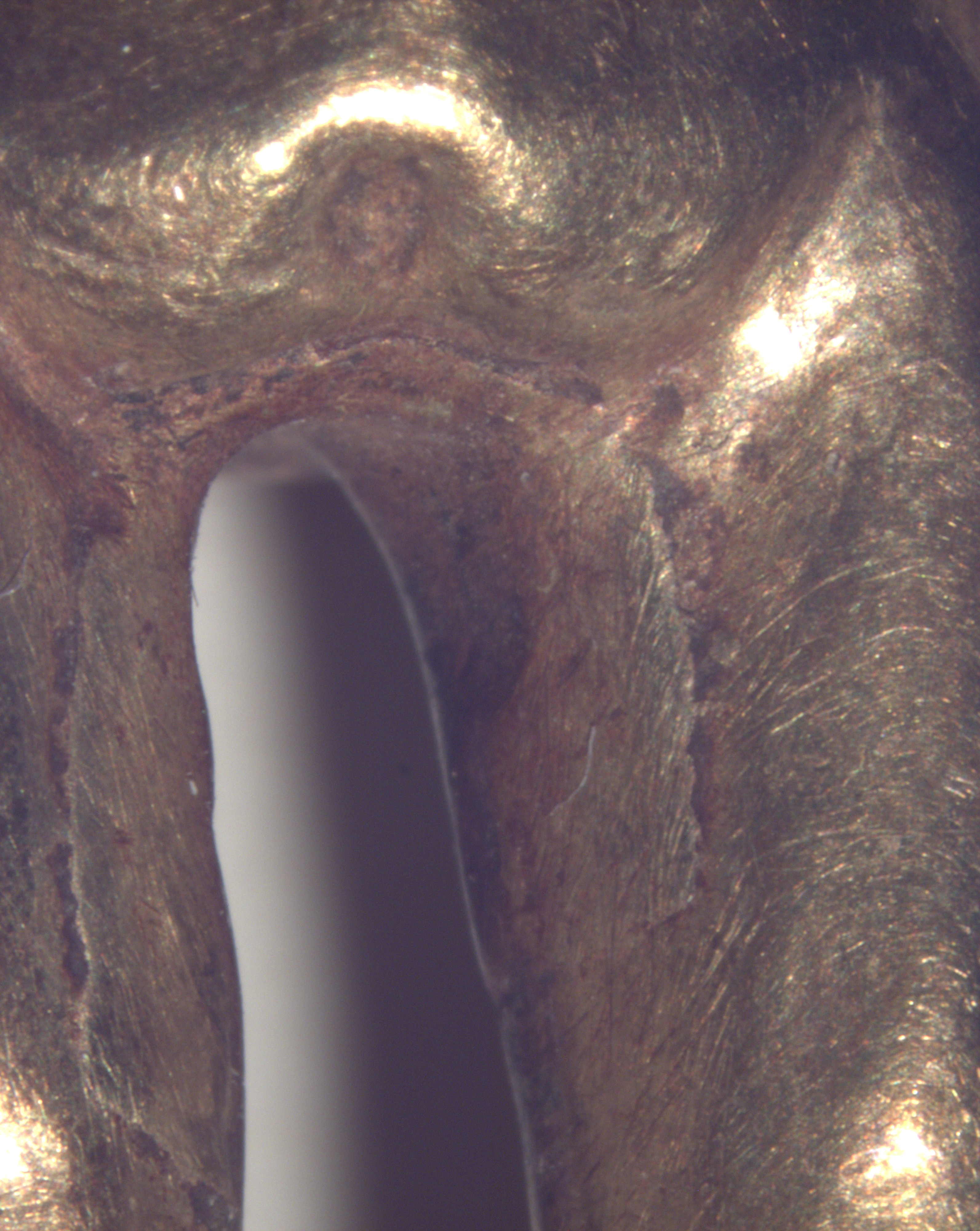

The relief areas of the figure—the breasts, hands and arms, and features of the face—were all created by initially hammering the metal from behind, what are now the interior surfaces, while the metal was placed onto a soft resilient surface. Additional details were accomplished from the front side using chasing tools, especially on the face, while engraving tools were used to delineate the fingers, toes, and hair plaits (see images 5 and 6). A combination of tracing and engraving was used for detailing the remainder of the hair (see image 7). The two tresses of hair are tied on the lower back, as seen on comparable Inca figurines, and the bar-like feature at their end may represent a tassel or ribbon akin to those used by women on the Peruvian altiplano today to fasten their hair (Valencia 1981, 57).

Similar to other figurines, there is a hammered depression extending down the back of the hair whose purpose is unknown. Its hammering may have helped facilitate the attachment of the hair piece to the head/torso/legs piece. The hair texture lines appear to have been made after the depression was rendered considering that they are sometimes visible in this depression and show no deformation. As with other female anthropomorphic figurines (e.g., 1995.481.5), there is a vertical line running along the center of the hair piece from the edge near the forehead (see image 6) toward the top of the hammered depression on the reverse. Could this central line have been made early in the construction of the figurine, as a way of planning the head/torso/legs component, indicating the halfway point of the sheet used to form it?

The single piece of metal used to form the head, torso, and legs was formed by hammering together a cylindrical form, with two cylindrical legs, which was closed through seams along the inner surface of each leg and up the center back and neck. A saddle shaped gusset was applied at the opening at the crotch (see image 8). Solder is visible in most of the joined areas by X-radiography. However, it is not clear if other methods of joining such as pressure welding were also used. The section of dome-shaped hair was raised from a flat piece of sheet and attached to the opening at the back top of the head also using solder.

At the site of Corral Redondo in the Churunga Valley in Peru, a range of metal and Spondylus figurines—anthropomorphic and camelid—were recovered accompanied by coca bags, or chuspas, covered in feathers, and other garments, including an uncu, or men’s tunic, an illiclla, or women’s shoulder cloth, and a red feather headdress usually associated with male figurines (King 2016). The metal figurine depicting a woman shows similar features to 1979.206.1058, including the central line on the hair piece, but appears to have a silvery surface and thicker feet pieces. Investigators believe that these materials from Corral Redondo were associated with the burial of several individuals—male and female—as part of a capac hucha deposition at the site, but the human remains were apparently destroyed after excavation and the miniature garments appear to have become associated with figurines different from those with which they were originally deposited or recovered, signs of the sheer disruptiveness brought to this sacred context. Tripartite divisions are notable in the social organization within the Inca empire: Collana (Inca), Cayao (non-Inca), and Payan (pre-Inca). As noted above, they are also recognized among the sizes of the human figurines in metal. A tripartite division may be seen in the metals used in the Inca empire and deployed in these figurines—copper, silver, and gold (Lechtman 2007, McEwan 2015). However, this division does not capture the fact that some of the figurines are alloys, such as gold-copper, while copper-tin alloys were a key feature of Inca metallurgy as well.

Technical notes: Optical microscopy, X-radiography, and XRF conducted in 2017.

Bryan Cockrell, Curatorial Fellow, AAOA

Beth Edelstein, Associate Conservator, OCD

Ellen Howe, Conservator Emerita, OCD

2017

Published References

Burger, Richard L., and Lucy C. Salazar. Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, cat. no. 169.

Further Reading

Cieza de León, Pedro de. The Incas. Edited by Victor Wolfgang von Hagen. Translated by Harriet de Onis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, [1553] 1959.

Cobo, Bernabé. History of the Inca Empire: An Account of the Indians' Customs and Their Origin, Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institutions. Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press, [1653] 1979.

Diez de Betanzos, Juan. Narrative of the Incas. Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton and Dana Buchanan. Austin: University of Texas Press, [1551–57] 1996.

King, Heidi. “Further Notes on Corral Redondo, Churunga Valley.” Nawpa Pacha 36, no. 2 (2016): 95–109.

Lechtman, Heather. “The Inka, and Andean Metallurgical Tradition.” In Variations in the Expression of Inka Power, edited by Richard L. Burger, Craig Morris, and Ramiro Matos Mendieta, 313–355. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2007.

McEwan, Colin. “Ordering the Sacred and Recreating Cuzco.” In The Archaeology of Wak’as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, edited by Tamara L. Bray, 265–91. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Valencia Espinoza, Abraham, Metalurgia Inka: Los ídolos antropomorfos y su simbología. Cusco, 1981.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.