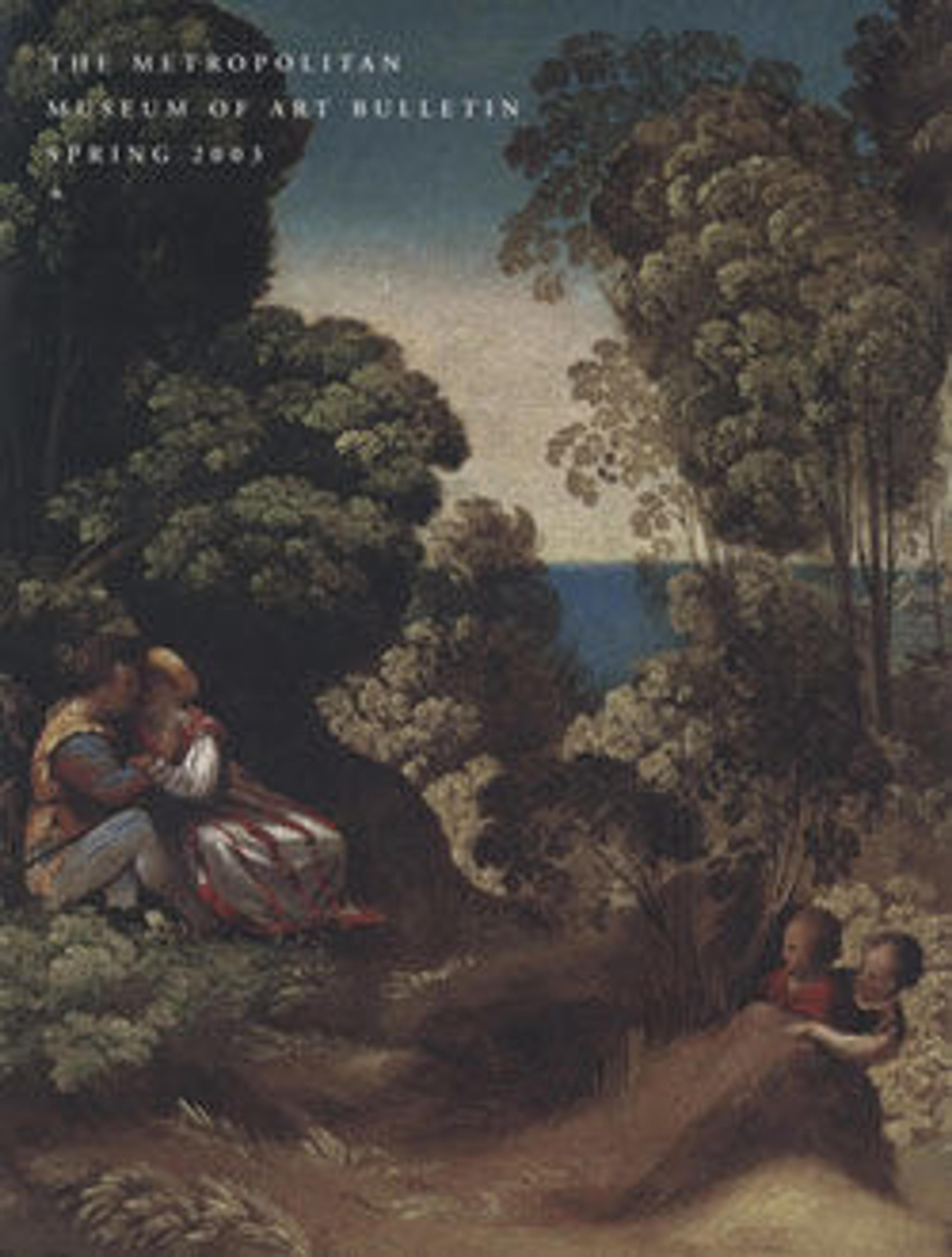

The Three Ages of Humans

In a lush landscape by the water, the three ages of humankind are represented by two boys peeping behind a bush, two lovers, and two old men. In Italy, landscape painting was inspired by classical literature and aimed to delight the eye while also depicting one or more narratives for viewers to uncover. The old men were added later by the artist, suggesting that the subject was originally a pastoral landscape that Dosso transformed into a narrative of the life cycle. Dosso’s wit, much prized at the court of Ferrara, is seen in the detail of the goats that appear to spy on the young lovers.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Three Ages of Humans

- Artist: Dosso Dossi (Giovanni de Lutero) (Italian, Tramuschio ca. 1486–1541/42 Ferrara)

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 30 1/2 x 44 in. (77.5 x 111.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Maria DeWitt Jesup Fund, 1926

- Object Number: 26.83

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.