Asian Art

About Us

The Department of Asian Art fulfills a unique role at The Met by representing the artistic achievements of six major cultural traditions that encompass 5,000 years of history, half the world's population, more than twenty modern nations, and a vast region that ranges from Afghanistan, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia across the Himalayas to China, Korea, and Japan.

The Met's collection of Asian art—more than 35,000 objects, ranging in date from the third millennium B.C. to the twenty-first century—is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the world. Each of the many civilizations of Asia is represented by outstanding works, providing an unrivaled experience of the artistic traditions of nearly half the world.

As Asia becomes ever more important on the world’s stage, the need to understand its diverse cultures and rich history becomes increasingly important. We at The Met want to do our part to make Asia more accessible by celebrating the ways in which the past continues to inform and enrich the present. We invite you to share in that adventure by exploring this page.

The Met has been collecting Asian art since the late nineteenth century. Many of its earliest benefactors—Benjamin Altman, the Havemeyers, the Rockefellers, and others—included objects from Asia in their large bequests to the Museum in the first half of the twentieth century, and in 1915, the Department of Far Eastern Art was established. The real impetus for creating a comprehensive collection of Asian art came from Douglas Dillon, who was elected president of the Museum's Board of Trustees in 1970. In 1986 the department's name was changed to the Department of Asian Art.

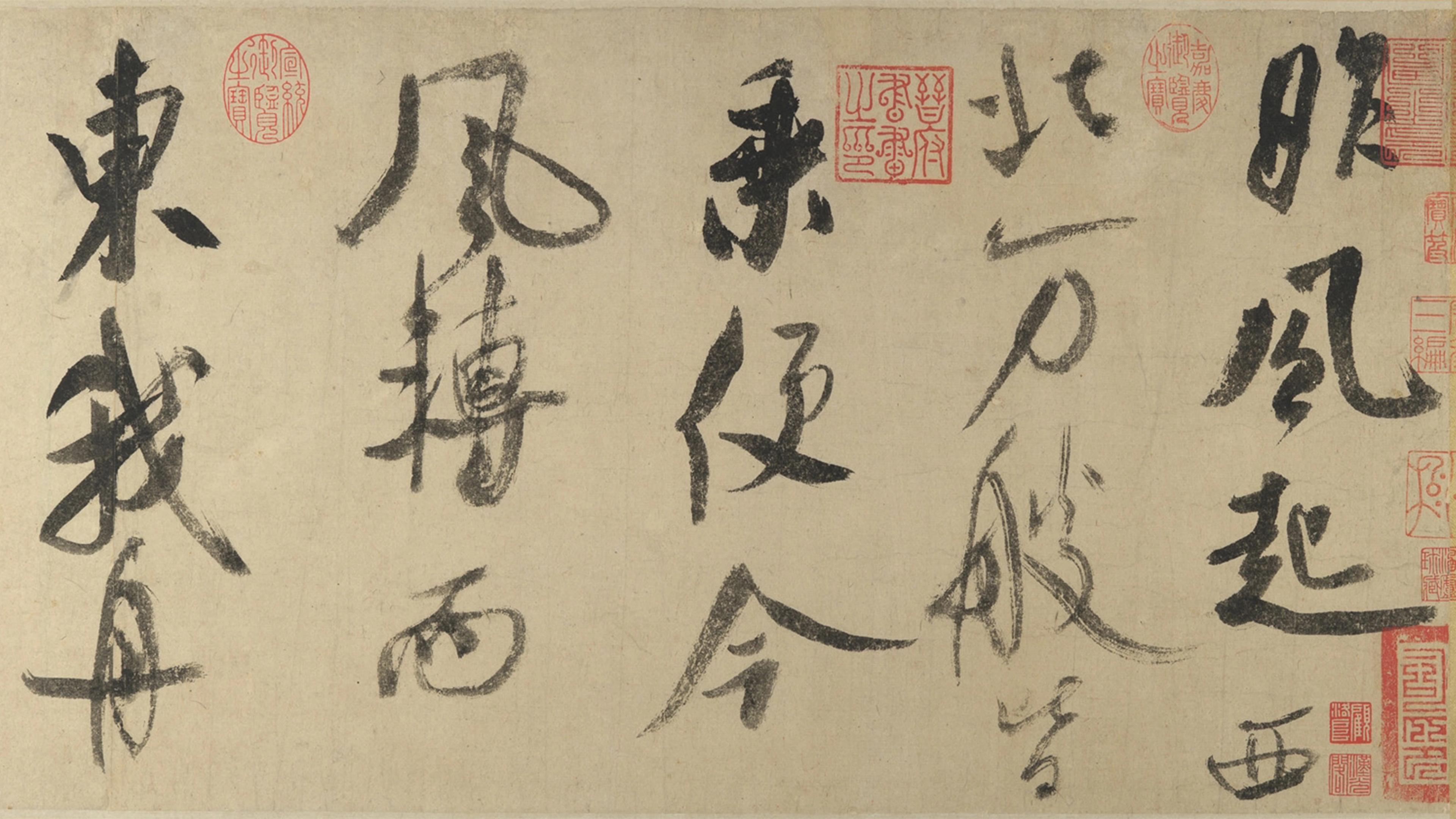

The Metropolitan Museum of Art devotes some 64,500 square feet of gallery space to the presentation of Asian Art, including paintings, calligraphy, prints, sculptures, metalwork, ceramics, lacquers, works of decorative art, and textiles from East Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Himalayan kingdoms, and Southeast Asia.

The galleries in the Asian Wing are arranged geographically and chronologically. As distinct as the cultures of Asia are from one another, many pieces in the collection reveal similarities in form and iconography occasioned by the sharing of religions, such as Buddhism and Hinduism, or themes and techniques, such as those found in blue-and-white ceramics or ink painting. Thus, an exploration of the works on view yields both an appreciation of the art of Asia's many diverse cultures and an understanding of the ties between these traditions.

Certain gallery installations, such as those of Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Indian, and Tibetan paintings, rotate every six months, and displays of more fragile textiles, lacquers, and woodblock prints change approximately every four months. These rotations enable the Department to create focused installations and thematic exhibitions that highlight different aspects of the permanent collection.

Art

Featured Collections

Articles, Audio, and Video

Featured

The Latest

Research

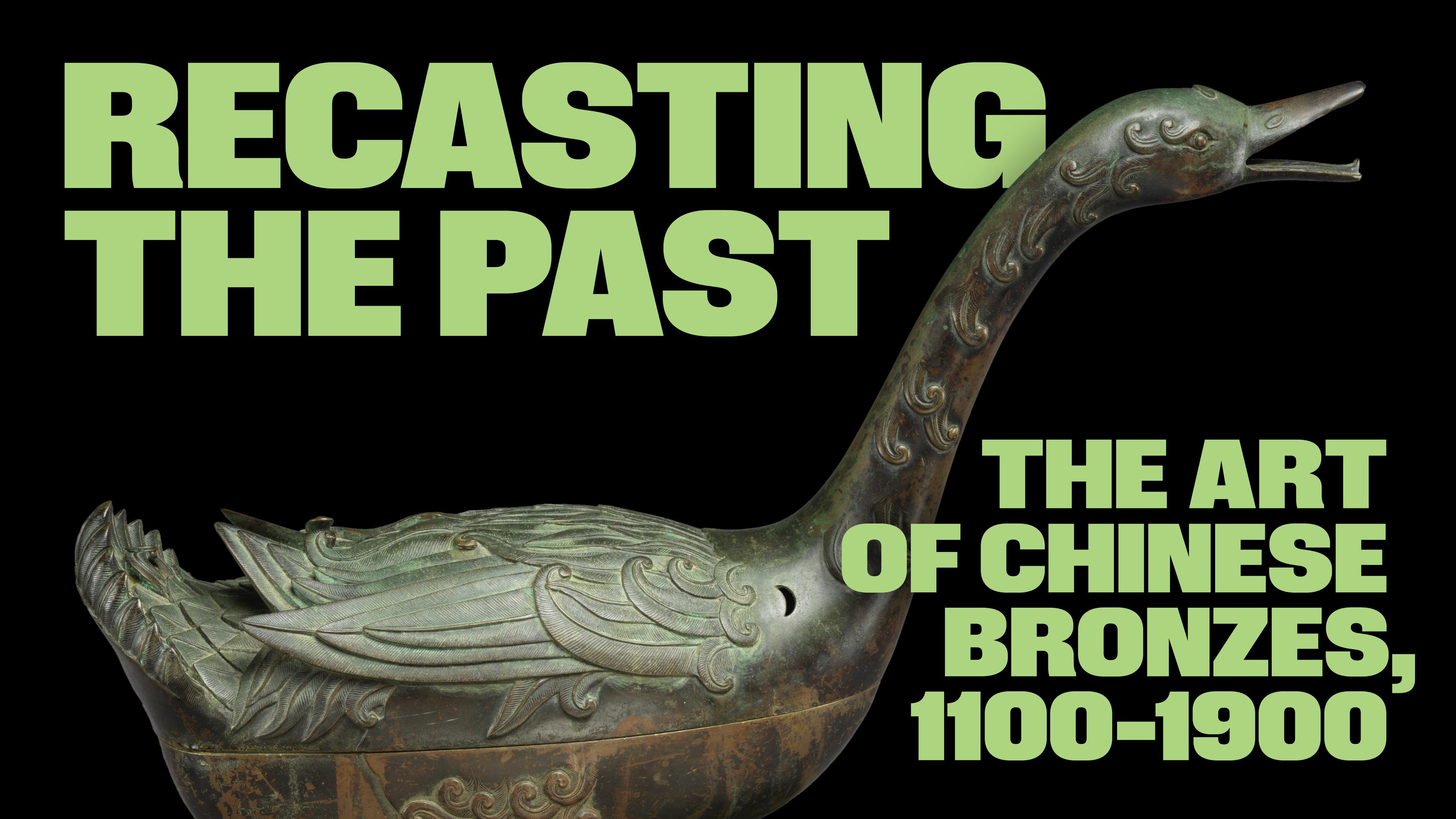

Exhibitions

Press the down key to skip to the last item.