Alexandria Ballroom

Alexandria, Virginia, 1792

Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

Since the American Wing opened in 1924, this large and imposing room has been referred to as the Alexandria Ballroom, installed in Gallery 719. Intended to host public assemblies and elegant balls, it was originally located on the second floor of the City Hotel, built in 1792 in Alexandria, Virginia. Under the direction of one of its early proprietors, John Gadsby (1766–1844), the hotel and its adjoining tavern hosted many notable guests, including early American presidents, politicians, and foreign dignitaries. The ballroom at Gadsby's Tavern, as it came to be known, held numerous historical events: George Washington celebrated his last two birthdays (1798 and 1799) in this room, and Thomas Jefferson's inaugural banquet occurred here in 1801. To accommodate its multiple functions, the room was sparsely furnished with Windsor side chairs like those displayed in the musician's gallery, or with simple early Federal-style chairs lining the walls. Today, it serves as a gallery for displaying highlights from the Museum's collection of American eighteenth-century furniture, along with paintings from the same era.

View of the Alexandria Ballroom with musician's gallery.

The City Hotel and Tavern

View of Gadsby's Tavern. Library of Congress

The City Hotel was constructed in 1792 on the corner of North Royal and Cameron Streets in Alexandria, Virginia. Tavern keeper John Wise (1738–1815) commissioned it as an addition to his adjacent tavern, which was already a popular meeting place for locals and travelers alike. In 1793, following the completion of the building, he advertised a "new and elegant Three-Story Brick-House…which was built for a Tavern, and has twenty commodious, well-finished Rooms in it." The three-story, four-bay facade reflects the eighteenth-century American preference for symmetrical, classically inspired English architectural design. The hotel was on the mail stage and coach lines that traversed the mid-Atlantic region and provided a continuous flow of customers traveling to and from the nation's capital in Washington, D.C.

English-born John Gadsby (1766–1844) leased the property from Wise in 1796 and assumed operation of the establishment until 1808. Under his management, Gadsby's Tavern became the center of social and political life in Alexandria. The dual structure continued to operate as a hotel under various proprietors until the late nineteenth century.

Setting

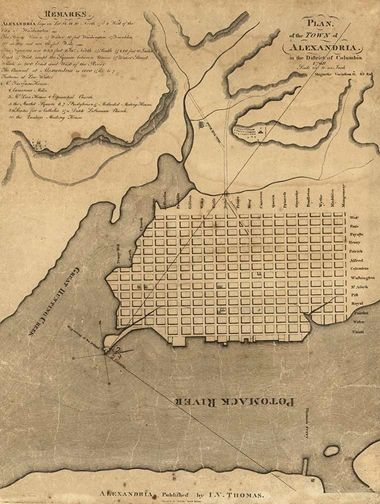

Situated on the Potomac River, Alexandria was established as a British colonial fort in the seventeenth century. By the late eighteenth century, it had developed into a sizable town with a large population of merchants and craftsmen. It was also a robust trading port for tobacco, wheat, and imported goods. The agricultural commodities traded out of Alexandria were largely harvested by enslaved people on the nearby plantations owned by Virginia's elite class of landed gentry, including George Washington, who resided about ten miles south at Mount Vernon.

In 1789, the city was included among the lands Virginia ceded to form the District of Columbia, the nation's new capital. When John Wise constructed his new hotel, Alexandria boasted a population of just under three thousand people, about one-fifth of whom were enslaved. As the premiere port on the Potomac River, the city continued to grow in subsequent decades; however the physical destruction of the District of Columbia by British troops during the War of 1812, along with later economic recessions, prevented the municipality from keeping up with the nation's other booming ports, such as nearby Baltimore, Maryland. Alexandria and the other lands on the southern shores of the Potomac River were ultimately returned to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1847.

Image: Plan of the town of Alexandria in the District of Columbia, 1798. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Interior

View of the Alexandria Ballroom

Tavern ballrooms, like the one at Gadsby's Tavern, were meant to be multi-purpose and flexible. Often the most elegant room in an establishment, it hosted balls, concerts, lectures, auctions, club meetings, and other large gatherings. An 1802 inventory of the ballroom reveals that among its sparse furnishings were objects related to lighting (chandeliers, looking glasses) and heat (fireplace implements) as well as curtains and blinds. Chairs, tables for dining, and other furniture could be brought in or taken out as needed. The raised balcony provided a gallery for musicians that both maximized the space in the ballroom and amplified the sound of the music.

Although it was the site of refined entertainments, the plastered walls and chair-rail-height dados reflected the practical side of the room's function. Higher up, away from the scuffs and kicks of furniture, hands, and feet, the room's richly carved ornament is ordered, almost perfectly symmetrical, and reflects the principals and motifs of Georgian decoration, a waning style in the 1790s when the room was built and Neoclassicism was on the rise in America.

English interpretations

Left: Plate L from Abraham Swan's The British Architect (1745). Right: Chimney-breast in the Alexandria Ballroom

The rich woodwork of the ballroom reflects the continuation of the Georgian decorative tradition into the early Federal period. The scrolled pediments over the doors and mantels, the flared moldings that embellish the doorways, windows, and mantels, the fretwork chair rail, and the dentil-molded cornice are similar to examples popularized by English pattern books of the 1740s and 1750s. The room's two chimney-breasts are a simplified version of a design from Abraham Swan's The British Architect (1745). Though Swan was most popular in the colonies in the period preceding the revolution, an American edition of his book was published in Philadelphia in 1775 and his classically inspired designs remained in use in the decades following American independence.

Social gatherings

George Cruikshank. Dos-a-dos - Accidents in Quadrille Dancing, 1817. England. Hand-colored etching on paper. Art Institute of Chicago

The ballroom at the City Hotel and Tavern offered Alexandrians a large meeting space that served a variety of functions for different occasions. Newspaper advertisements record that the ballroom, often referred to as "the assembly room", hosted club and society meetings, instrumental and vocal concerts, lectures, and individual entertainers such as ventriloquists. Dance assemblies were common. The tavern also served as a ticketing vendor for other such events hosted in the city.

Although Gadsby's Tavern maintained a well-regarded reputation, the patrons that taverns attracted also made them possible places of misdeeds and indulgence. In 1798, Gadsby explicitly advertised in the Alexandria Advertiser that his tavern was "supplied with every article requisite for the comfort of those who honor him with their custom…It shall be his peculiar duty to merit their favor by preserving order and propriety. For the more effectually carrying this his intention into execution, no species of gambling whatever will be allowed…."

George Washington's birthnight alls

Jean-Léon Gerome Ferris, The Victory Ball, 1781, ca. 1929. Virginia Historical Society, Lora Robins Collection of Virginia Art

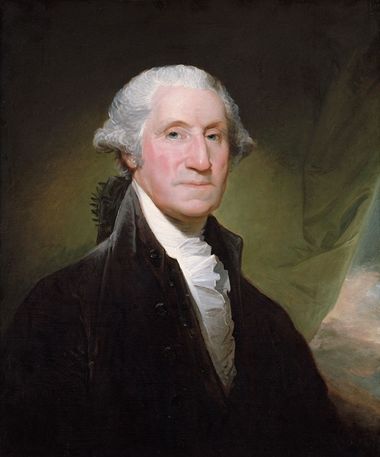

The most remembered events to occur at Gadsby's Tavern were annual birthnight balls for George Washington. Following the English tradition of celebrating the birthday of the monarch, the public celebration of George Washington's birthday began in 1778 at Valley Forge. Washington, who was noted for his skill in and love of dancing, attended the parties held in his honor at Gadsby's Tavern in 1798 and 1799, after he had retired from the presidency in 1797. He recorded in his diary on February 11, 1799; "Went up to Alexandria to the celebration of my birth day. Many Manœuvres were performed by the Uniform Corps and an elegant Ball & Supper at Night." It was to be the last birthnight balls he attended. In November of that year, the Alexandria General Assemblies organization invited Washington to an upcoming series of dances. Washington declined stating, "Mrs Washington and myself have been honoured with your polite invitation… But alas! our dancing days are no more." He died about a month later on December 14, 1799.

The most remembered events to occur at Gadsby's Tavern were annual birthnight balls for George Washington. Following the English tradition of celebrating the birthday of the monarch, the public celebration of George Washington's birthday began in 1778 at Valley Forge. Washington, who was noted for his skill in and love of dancing, attended the parties held in his honor at Gadsby's Tavern in 1798 and 1799, after he had retired from the presidency in 1797. He recorded in his diary on February 11, 1799; "Went up to Alexandria to the celebration of my birth day. Many Manœuvres were performed by the Uniform Corps and an elegant Ball & Supper at Night." It was to be the last birthnight balls he attended. In November of that year, the Alexandria General Assemblies organization invited Washington to an upcoming series of dances. Washington declined stating, "Mrs Washington and myself have been honoured with your polite invitation… But alas! our dancing days are no more." He died about a month later on December 14, 1799.

Image: Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828). George Washington, begun 1795. Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 25 1/4 in. (76.8 x 64.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.160)

John Gadsby

Born in England, John Gadsby (1766–1844) assumed the management of the City Hotel and Tavern in 1796, leasing the property from its former proprietor, John Wise (1738–1815). Research suggests that Gadsby was married three times. After his first wife, Sarah Sofia, died in 1805, he married Margaret McLaughlin (d. 1812) just a few months later. Following Margaret's death in 1812, he married Providence Norris (1786–1858). He had six children who survived to adulthood. His successful management of Gadsby's Tavern launched him in a longstanding career in the hospitality industry in the young American republic. A visitor to one of his later establishments described Gadsby as "a short, stout gentleman," with an "urbane manner."

Born in England, John Gadsby (1766–1844) assumed the management of the City Hotel and Tavern in 1796, leasing the property from its former proprietor, John Wise (1738–1815). Research suggests that Gadsby was married three times. After his first wife, Sarah Sofia, died in 1805, he married Margaret McLaughlin (d. 1812) just a few months later. Following Margaret's death in 1812, he married Providence Norris (1786–1858). He had six children who survived to adulthood. His successful management of Gadsby's Tavern launched him in a longstanding career in the hospitality industry in the young American republic. A visitor to one of his later establishments described Gadsby as "a short, stout gentleman," with an "urbane manner."

After leaving Alexandria in 1808, Gadsby went on to manage the India Queen Hotel in Baltimore, where he remained until 1823. A few years later he opened his own establishment, the National, in Washington, DC, on Pennsylvania Avenue at Sixth Street. The National went on to become one of the city's most renowned hotels. When Gadsby retired in 1836, his son William carried on the management of the National until 1844, when it was sold out of the family. The hotel, which became well-known through its notable guests and various scandals, operated until the 1929.

Image: John Gadsby Chapman (American, 1808–1889). John Gadsby, 1833. Oil on canvas, 58 3/4 x 48 3/4 in. (framed). Gadsby's Tavern Museum

Later proprietors and owners

Exterior of Gadsby's Tavern, ca. 1920. Library of Congress

Following Gadsby's 1808 departure to Baltimore, the City Hotel and Tavern was managed by a quick succession of proprietors, including William Caton, James Brook, and Thomas Triplett. Upon John Wise's death in 1815, the property was sold to Thomas Irwin, who like Wise, leased the establishment to others. Various hotels operated in the building until the late nineteenth century. Other commercial endeavors later occupied the space, and by the early twentieth century it had fallen into disrepair. The Museum purchased the ballroom's architectural elements from Irwin's descendants in 1917.

In 1928 the historic building was threatened with demolition, and local residents rallied to preserve the structure. Alexandria's American Legion Post #24 purchased the structure in 1929 and undertook essential repairs to preserve the building for future generations. After years of careful stewardship, the American Legion donated the building to the City of Alexandria in 1972, which restored the structure and re-opened it to the public in 1976 for America's bicentennial celebration, which saw the preservation of many colonial buildings across the East Coast. Today, it is owned and operated as a museum and restaurant by the City of Alexandria.

Slavery at the City Hotel and Tavern

To serve guests at the City Hotel and Tavern and maintain his personal household, Gadsby and other proprietors of the business relied on the labor of enslaved individuals until the Civil War. According to an 1802 inventory, Gadsby enslaved eleven people to labor and serve at his Alexandria tavern: Tom, Anney, John, Aron, Ranny [?], William, Gowen, Godfrey, Henny, and two men who were both named Mosses. Newspaper advertisements document that Gadsby's frequently sought to purchase or hire others' enslaved men to work at the hotel as cooks, smiths, and the hostlers who tended the guests' horses. Shortly before Gadsby departed for Baltimore in August 1808, James Lewis, who was enslaved by Gadsby as a hostler, self-emancipated. Gadsby offered a $50 reward for Lewis's return and noted in the advertisement he had a large scar on his face from being kicked by a horse, a hazard of his forced occupation. It is unknown if Lewis reached freedom.

To serve guests at the City Hotel and Tavern and maintain his personal household, Gadsby and other proprietors of the business relied on the labor of enslaved individuals until the Civil War. According to an 1802 inventory, Gadsby enslaved eleven people to labor and serve at his Alexandria tavern: Tom, Anney, John, Aron, Ranny [?], William, Gowen, Godfrey, Henny, and two men who were both named Mosses. Newspaper advertisements document that Gadsby's frequently sought to purchase or hire others' enslaved men to work at the hotel as cooks, smiths, and the hostlers who tended the guests' horses. Shortly before Gadsby departed for Baltimore in August 1808, James Lewis, who was enslaved by Gadsby as a hostler, self-emancipated. Gadsby offered a $50 reward for Lewis's return and noted in the advertisement he had a large scar on his face from being kicked by a horse, a hazard of his forced occupation. It is unknown if Lewis reached freedom.

In May 1810 a newspaper notice announced that the then-manager of the City Hotel, William Caton, was selling property to satisfy a debt. An upcoming sale was to include an enslaved Black man who labored as a cook and was recognized as "one of the best in the United States." The ad was sure to highlight that the forty-five year old man was "brought up by Mr. George Mann of Annapolis," a noted publican who also hosted many notable historical figures at his own tavern. Caton, formerly of Annapolis, likely brought the unnamed man to Alexandria when he assumed management of the City Hotel in 1808. The man's whereabouts after Caton's sale, and his name, remain unknown.

In the antebellum period, Alexandria became a major port in the interstate trade of enslaved people. As the cultivation of cotton, sugar cane, and other labor intensive crops increased in the lower South, many enslavers in the upper South opted to sell the people they enslaved for high profits. However, at the onset of the Civil War, Alexandria was occupied by Union troops and became an important waystation for enslaved individuals fleeing the Confederacy.

Top: A notice issued by John Gadsby regarding James Lewis published in the Alexandria Gazette, August 31, 1808. Bottom: The notice advertising the upcoming sale of the Black cook who labored at the City Hotel and Tavern, published in the Alexandria Gazette, May 22, 1810

Notable guests

Alexandria's close proximity to the nation's capital, its position along well-traveled stage coach lines, and its bustling port brought a number of notable guests to the City Hotel and Tavern. One of the most famous guests at Gadsby's Tavern was George Washington. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were also a frequent guests, passing through the city on their travels to and from their Virginia plantations. Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin also patronized the establishment under its various owners.

Alexandria's close proximity to the nation's capital, its position along well-traveled stage coach lines, and its bustling port brought a number of notable guests to the City Hotel and Tavern. One of the most famous guests at Gadsby's Tavern was George Washington. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were also a frequent guests, passing through the city on their travels to and from their Virginia plantations. Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin also patronized the establishment under its various owners.

At the invitation of President James Monroe, the Marquis de Lafayette returned to the United States in July of 1824 to embark on a year-long, nation-wide tour, celebrating his contributions to the American Revolution. The event was a national sensation, and surviving commemorative objects—including transfer-printed ceramic plates, salts, and decorative plaques, along with a variety printed ephemera—testify to the frenzied activity the country engaged in to honor this revolutionary icon. During his stay in Washington, the marquis dined at Gadsby's Tavern, then under the management of Horatio Claggett, before continuing on to Virginia the next day, where he visited Washington's tomb at Mount Vernon. The ballroom's association with this celebratory cast of clients motivated curators at The Met to acquire this room.

Image: Rembrandt Peale (American, 1778–1860). The Marquis de Lafayette, 1825. Oil on canvas, 34 1/2 x 27 3/8 in. (87.6 x 69.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.19)

Acquisitions of the Room

As plans to establish the American Wing formed in the early twentieth century, curators began to acquire historic interiors and architectural elements to use as both period rooms and galleries to display the American Wing's decorative arts collections. Curator Durr Friedley identified the ballroom from Gadsby's Tavern as an ideal candidate writing, "No other room similar to this is known to exist in the United States… The design ranks with the best, the size is unique, and the historical connection with Washington and Lafayette adds to its interest as a Museum specimen."

As plans to establish the American Wing formed in the early twentieth century, curators began to acquire historic interiors and architectural elements to use as both period rooms and galleries to display the American Wing's decorative arts collections. Curator Durr Friedley identified the ballroom from Gadsby's Tavern as an ideal candidate writing, "No other room similar to this is known to exist in the United States… The design ranks with the best, the size is unique, and the historical connection with Washington and Lafayette adds to its interest as a Museum specimen."

The Museum purchased the woodwork from the ballroom in 1917, along with two chimney breasts from the first floor, and the doorway to the City Hotel building. The latter elements were deaccessioned by the Museum, and the doorway and one chimney breast were returned to their original location within Gadsby's Tavern and now belong to the Gadsby's Tavern Museum.

Image: Mantelpiece from the ground floor of Gadsby's Tavern installed an alcove in the American Wing, 1924. This mantelpiece has been deaccessioned and now belongs to the Gadsby's Tavern Museum

A gallery for connoisseurship

The Alexandria Ballroom, as installed in 1924 and published in A Handbook of the American Wing Opening Exhibition (1924) by R. T. H. Halsey and Charles O. Cornelius

Since the American Wing opened in 1924, the ballroom has been used as a traditional gallery, rather than a furnished period room. The early purpose of the gallery was to educate the public about eighteenth-century American furniture, then viewed as the pinnacle of American design, by encouraging close-looking at highlighted objects in the collection. The first handbook on the American Wing explained, "The very considerable wall space in this large room affords an opportunity for the arrangement of a series of side chairs, which show the employment of the cabriole leg and of the solid splat back through its simplest and earliest forms to its highly developed expression… About the room are set not only chairs but tables… [that] show various characteristics and treatments of the period." The furniture was complemented by a selection of paintings, all by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), who was commended as "America's great native-born portrait painter."

This focus on fine handcraftsmanship, identifying regional variations in design, and highlighting exceptional examples of colonial fine art, decorative arts, and architecture reflected the Colonial Revival movement that peaked in the 1920s in part in reaction to the huge wave of millions of European immigrants to the United States in the preceding decades. The founders of the American Wing sought to elevate America's colonial past as a means of inspiring these new immigrants to learn about and admire American history, as well as a way of improving contemporary design. Historic figures were revered, as were objects associated with their lives. The Alexandria Ballroom, a room once occupied by George Washington and other "Founding Fathers," and the furniture from the colonial era placed on view in it were seen as model expressions of national taste and culture.

Decorative details

Prior to its installation at the Museum, the ballroom woodwork was stripped of its paint—a typical approach to "restoration" in the early twentieth century. For many years it was painted "a light green-gray" that was thought to reproduce "as exactly as possible the original color found under many layers of more recent paint when the woodwork was cleaned." However, in 2006, scientists were unable to find any remnants of original paint on the room's woodwork to back up this claim.

Luckily, when the Museum purchased the ballroom's architectural elements in 1917, it left the original windows sashes in situ, only removing the ballroom's decorative woodwork. Paint analysis was conducted on the remaining window sashes at the Gadsby's Tavern Museum, and it confirmed that the room was originally painted a vibrant blue, a popular interior color in the eighteenth century. For the 2009 renovation of the American Wing, this color was reproduced using period pigments that were hand blended into oil-based paint, which was then applied to the woodwork using eighteenth-century painting techniques.

Gadsby's Tavern today

Every year, the Gadsby's Tavern Museum hosts a reenactment of George Washington's 1799 birthnight ball. Gadsby's Tavern Museum

Gadsby's Tavern still stands and is operated as a museum and restaurant by the City of Alexandria. The site is among very few historic taverns to remain standing and offers visitors a rare look at tavern culture, a critical fixture of colonial and early American social life. Over the years, Gadsby's Tavern Museum has undertaken significant research to understand the history of the dual structure and the lives of its occupants, laborers, and visitors, much of which has informed this feature. As part of its annual calendar of events, the museum recreates Washington's birthnight ball every February.

American Georgian Interiors (Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

Read more about American Georgian interiors like the Alexandria Ballroom on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.