Baltimore Room

Baltimore, Maryland, 1810–11

Matthew Thurlow, Research Associate; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

This room, installed in Gallery 724, comes from a townhouse for the Baltimore, Maryland, merchant and shipowner Henry Craig (1767–1832). Although it served as the Craig family's parlor, the Museum has furnished the space as a dining room since the American Wing opened in 1924. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, Americans began dedicating a specific room to dining, which they used in conjunction with a formal parlor for entertaining guests.

The geometric shapes found in the interior woodwork and on the inlaid Baltimore-made furniture are excellent examples of the adoption and adaptation of the English Neoclassical style in the early Federal period.

Image: The Baltimore Room in the American Wing.

Elegant surroundings

The architectural elements of the Baltimore Room are from the parlor of a brick row house located at 915 East Pratt Street (previously Queen Street, now demolished) that was built for Henry Craig in 1810 and 1811. The dates of construction can be defined rather precisely because in April 1810, Craig purchased an undeveloped lot for $1,500, and on November 1811, a fire insurance survey lists a completed house and outbuildings valued at $7,000.

The parlor was the most important room in Craig's dwelling devoted to entertaining guests. Accordingly, it contained the finest woodwork, which illustrates a delicacy and restraint typical of the Neoclassical style of the period.

Image: The Baltimore Room in the American Wing.

Dining in America

Although the Baltimore Room served as the Craig family's parlor, the Museum has always furnished the space as a dining room. In the late eighteenth century, wealthier Americans began to follow European fashions and dedicate a specific room to dining, which they used in conjunction with a formal parlor to entertain guests. In the early Federal period, when the fashion for dining rooms had made its way into middle-class homes, such specialized rooms were principally outfitted with a dining table, a suite of chairs, a sideboard, a variety of silver plate, and ceramic and glass tableware. In the Craig's residence the dining room was located on the main floor, connected to the principal parlor but positioned to the rear of the residence—a common layout in middle-class town house. Throughout the nineteenth century, dining became increasingly ritualized. A new genre of literature devoted to domestic management espoused prescribed menus, seating arrangements, service practices, manners, decorative schemes, and tablescapes in an effort to define elegance and refinement amidst a growing middle class that sought to assert its gentility along with its newfound financial success.

Since the Museum curators in the early 1920s found the architecture of the East Pratt Street house's parlor to be more interesting than that found in the actual dining room, they chose to interpret the parlor as the dining room in an effort to highlight this important social and architectural development.

Image: Henry Sargent (American, 1770–1845). The Dinner Party, ca. 1821. Oil on canvas, 61 5/8 x 49 3/4 in. (156.53 x 126.36 cm). The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Mrs. Horatio Appleton Lamb in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Winthrop Sargent (19.13)

Setting

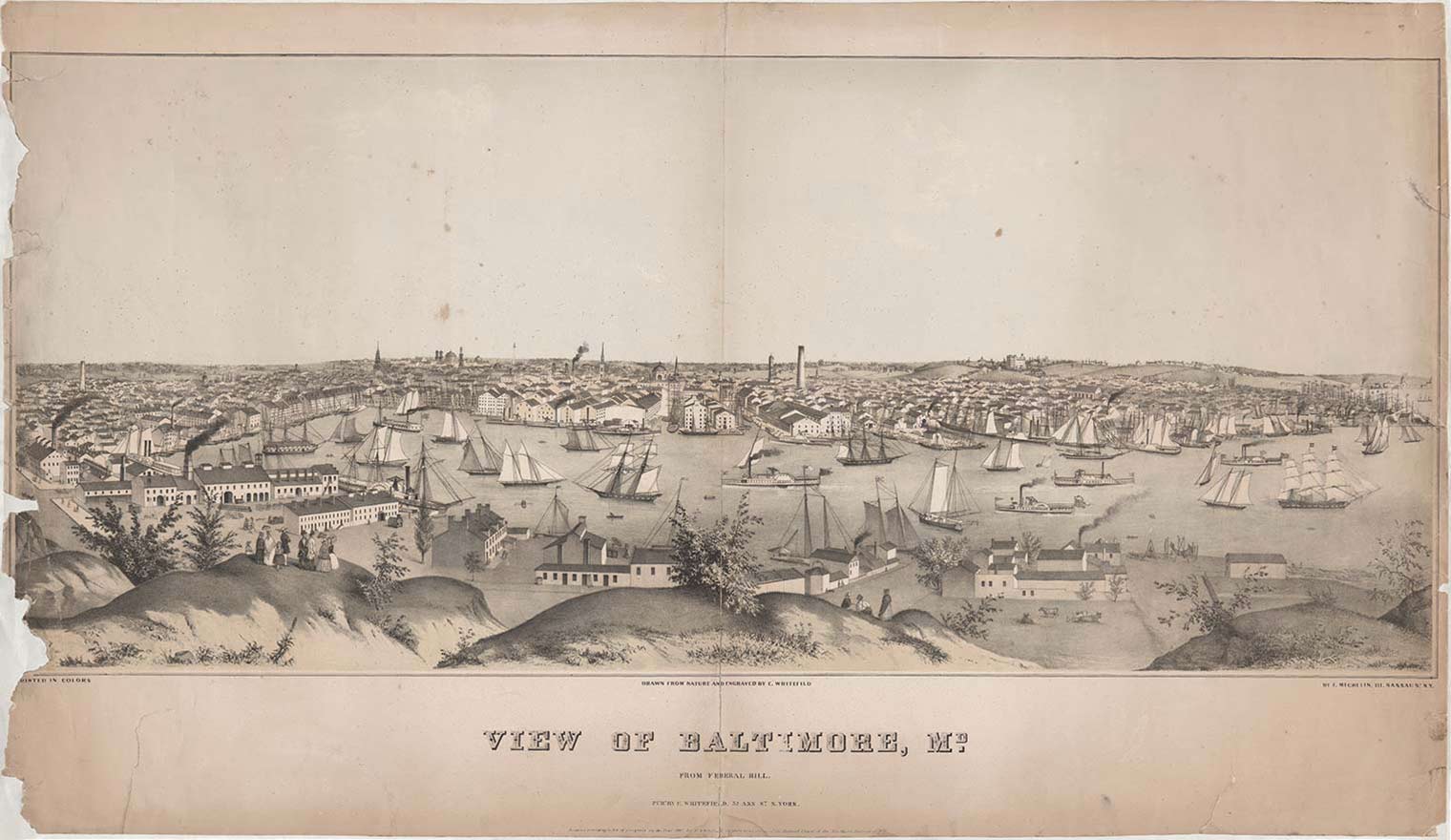

Merchants and ship owners such as Henry Craig built their houses close to the wharves. Edwin Whitefield (1816–1892). View of Baltimore, Md. from Federal Hill, ca. 1847. Lithograph, color, 24 x 41 3/8 in. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Merchants and ship owners such as Henry Craig built their houses close to the wharves. Edwin Whitefield (1816–1892). View of Baltimore, Md. from Federal Hill, ca. 1847. Lithograph, color, 24 x 41 3/8 in. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In the period during which Henry Craig's house on East Pratt Street was being built, Baltimore, was emerging as a major Atlantic port. By 1810 it was the third largest city in the United States, with a population of about 46,500 people, which included approximately 4,600 enslaved individuals and 5,600 free people of color. The city's commercial success was manifested in the extensive development of its residential neighborhoods. With access to agricultural products and timber from the American interior and imports from Europe and Asia, Craig and his counterparts in the mercantile and shipping industries grew wealthy from the steady transatlantic trade.

Exterior

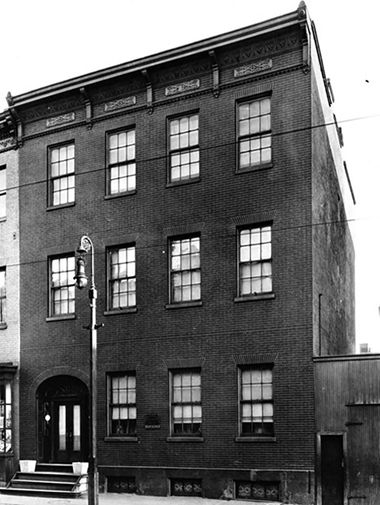

Like most Federal-style structures, Henry Craig's house featured a flat, plain facade with external ornamentation limited to the brick flat arches above the windows and a brick arch leading to the recessed front door with fan- and sidelight decorations. A long, two-story extension at the back of the house contained a kitchen, a pantry, and other work spaces, with bedrooms above. According to an 1811 fire insurance survey, the Craigs also owned a one-and-a-half-story carriage house and stable.

Although the architect and builder of the house are unknown, Craig lived two doors away from Ludwig Herring, a prominent Baltimore carpenter and housewright.

Image: The Craig House on its East Pratt Street site around 1925. The building was originally two stories tall; the third floor was added in the late nineteenth century

Interior

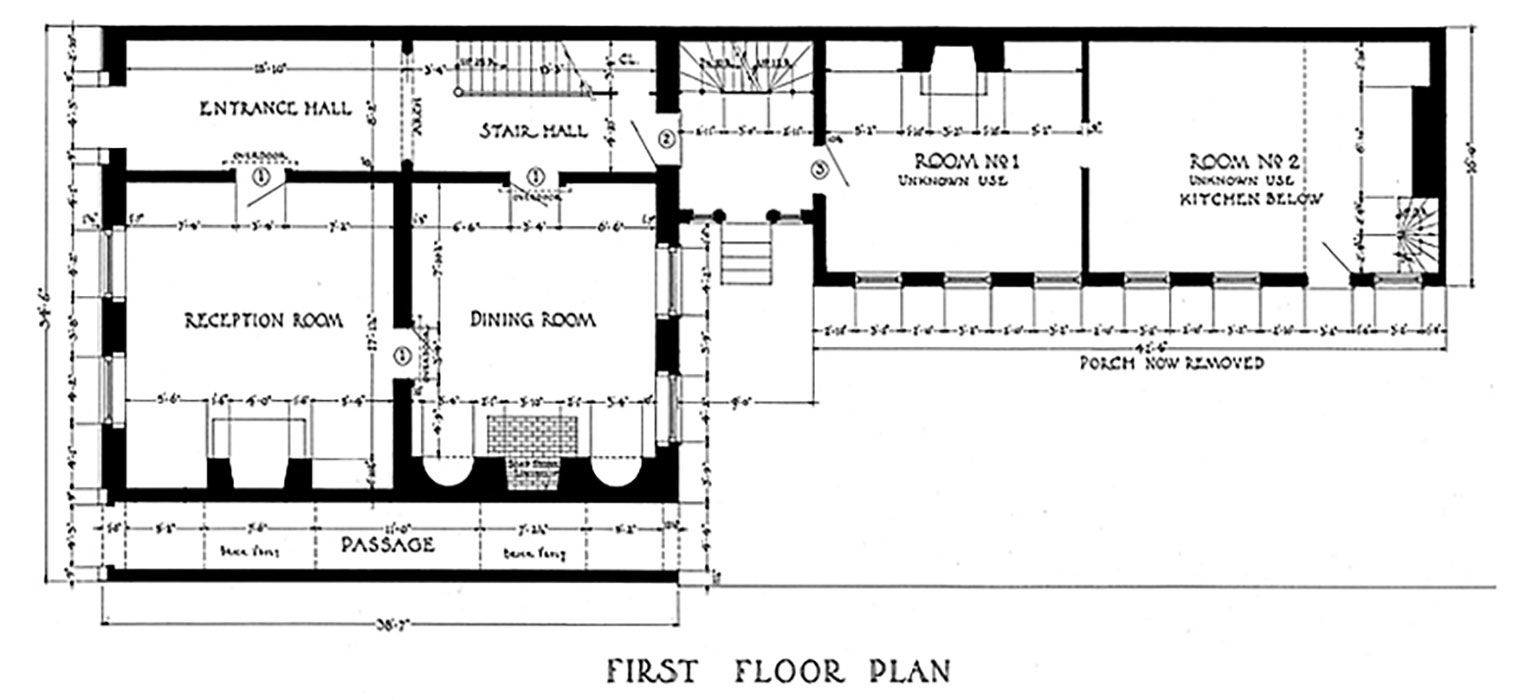

Floor plan of a typical early-nineteenth-century Baltimore row house. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The Craig House followed a typical floor plan for Baltimore houses of the period. The front door opened into a side hall with a staircase leading to the upper floors. Adjacent to the hall were a front parlor, which looked out onto the street, and a back dining room with a view to a side yard. Sleeping quarters for the family and enslaved individuals, and later domestic servants, were on the second floor of the main house and above the kitchen and pantry.

Unlike the elaborate, fully paneled fireplace walls of eighteenth-century homes, decorative woodwork in the Baltimore Room is limited to the mantel, the door and window surrounds, and the dado in the recessed alcoves. The repetition of oval panels and rounded pilasters are featured throughout the room's elements, which were crafted entirely from pine.

Changes over time

Although the East Pratt Street house was altered multiple times after its construction in 1811, little is known about its evolution. When the museum purchased the room in 1918, the parlor mantel had been relocated to the dining room, and one of the two alcoves had been enclosed. Most significantly, a third story had been added to the house at some point in the late nineteenth century.

A mid-twentieth-century photograph shows that the house had been changed from a residence into a commercial space. The broken windows and dilapidated condition foreshadow the structure's demolition in 1955.

Image: As indicated by the sign for Acme Tile Company, the Craig House was eventually used for commercial purposes. This photograph was taken in the 1950s, shortly before the house was demolished. American Wing files

The Craigs

This painting indicates the proximity of Baltimore's residential neighborhoods to the busy post. Nicholas Calyo (1799–1884), A View of the Port of Baltimore, 1836. Gouache on paper highlighted with pastel. Baltimore Museum of Art

Little is known about Henry Craig (1767–1823), the builder of the East Pratt Street townhouse. In the 1790s Craig served in Martinique as a United States agent for the relief of American sailors detained by the British navy, and in his later career he was a merchant, warehouseman, and part-owner of a line of steamboats and packet ships that ferried passengers between Philadelphia and Baltimore. He married Ann Chenoweth (1772–1843) in 1803.

The Craigs lived a comfortable life, and an 1813 tax assessment suggests that their home was elegantly furnished. That assessment and the 1820 population census also mention that Henry and Ann enslaved a young woman, whose name is presently unknown. She labored as a domestic servant—a common practice among the city's more affluent residents. Following her husband's death, Ann Craig continue to own the house, residing with her great-niece in later years, until her own death in 1843. The house then passed to her niece and grand-niece, Catherine German and Anna Maria Gordon (née German).

Thalia Hall and East Baltimore's German community

Thalia Maennerchor, as pictured in Official Souvenir and Programme, 20th Triennial Saengerfest of the Nord-Oestlicher Saengerbund of America (Baltimore: Saengerfest Association of Baltimore, 1903)

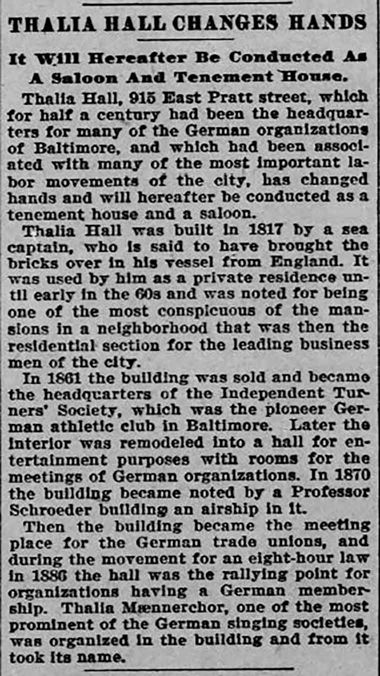

Census records and newspapers suggest that the house remained a residence until the 1850s. By that time, a large population of German immigrants had settled in East Baltimore, and the businesses and activities hosted at the East Pratt Street building over the next half-a-century served this community.

By 1860, the building was identified as Independent Turner Hall, or Turnhalle, a name derived from a German athletic organization. The athletic club was headquartered at the address, but it also served as a gathering space for other community organizations, political groups, and labor unions. City directories suggest that some residences were maintained on the upper floors, while a lively saloon, operated by a series of proprietors over the years, was located on the ground floor.

Ernest Lohmeyer and his sons took over the saloon in 1873, and the following year he built a ten-pin bowling alley in the adjacent lot. The Lohmeyers operated the space as a restaurant and also retailed liquor, wine, and cigars until Ernest Sr. suffered a mental breakdown in 1879. Bernard Nolte assumed management in 1883, and under his direction the building became known as Nolte's Hall and a popular meeting place for labor unions with large numbers of German-speaking members.

In 1890, August Knaup, a member of German singing group Thalia Maennerchor, took over the building and for the next thirty years, it would be known as Thalia Hall. Thalia Maennerchor was one of many German singing societies in Baltimore and they used the building as a clubhouse for ten years. The all-male choir performed locally and at regional gatherings, or saengerfests. A ladies auxiliary was also formed and the clubhouse hosted numerous practices and social events for the organization. Thalia Maennerchor moved into new headquarters in 1900 and the property was purchased by the Georgii family.

The Cuneos

When The Met purchased the Baltimore Room in 1918, the house was owned by Louis J. and Crescentia Cuneo. Louis (1878–1956) was a first-generation American citizen born to Italian immigrants, and in 1911 he married Crescentia Georgii Armiger (1878–1956). Crescentia's family acquired the East Pratt Street townhouse in the first years of the twentieth century, and under the Cuneos' ownership, the saloon continued to operate under the name Thalia Hall. Census records suggest that a portion of the upper floors were retained as residences, and the Cuneos lived there until the late 1920s. At the time the Museum acquired the architectural elements, Louis Cuneo was working as a foreman in Baltimore's shipyards, an active port for international and domestic trade. He was also a member of St. Leo's Catholic Church, located around the corner from Thalia Hall and a pillar of Baltimore's Little Italy community.

Throughout the years, the city's population continued to diversify, and the early twentieth century saw large numbers of Eastern European, Italian, and Greek immigrants settling in East Baltimore. East Pratt Street, on which Thalia Hall was located, was an unofficial demarcation line, dividing Little Italy to the south and East Baltimore's vibrant Jewish community to the north. The public venue continued to serve as a cultural and social gathering place for these new Americans.

Although the Cuneos sold the interior woodwork to the Museum, they appreciated its historical value. When Mrs. Cuneo moved out of the building in 1928, she wrote to The Met to express her fear of seeing "this old building with some of its old beauty go to wreck or be torn down for some factory." As Mrs. Cuneo feared, the area continued to change and industrial businesses moved into the former residence and meeting hall.

Arts of the young nation

The Baltimore Room shortly after the opening of the American Wing in 1924, as illustrated in R. T. H. Halsey and Elizabeth Towers’s The Homes of Our Ancestors (1925)

The Met acquired the Baltimore Room in 1918 in recognition of Baltimore's importance to the economy of the United States in the Federal period and the skill of the city's furniture craftsmen. The interior woodwork was taken from the parlor of the Craig House, but the room has been furnished as a dining room since the American Wing opened in 1924. The curators probably reasoned that the parlor woodwork was more architecturally significant than that found in the dining room. In addition, the Museum had acquired a choice Baltimore dining table in 1919.

Acquiring the Baltimore Room

A large assemblage of architectural elements from the Craig house came to The Met as a result of the 1918 purchase. From the parlor, the curators acquired the baseboards, the dado, the chair rail, the mantel, a doorway, and an alcove.

The Museum also selected an archway from the first-floor hall, an interior doorway with fanlight, and an exterior door with fan- and sidelights. Some of these elements are on display in the Federal Gallery (Gallery 723) adjacent to the Baltimore Room.

Image: The Federal Gallery, ca. 1940. The doorway with fan- and sidelights came from East Pratt Street

On exhibit

The Baltimore Room accurately depicts the room's position within the Craig House. The doorway that now leads to the Benkard Room (Gallery 725) originally led to the hallway, and the doorway to the Federal Gallery (Gallery 723) provided access to the dining room. However, to make up for the elements not included in the 1918 purchase, a second door surround and alcove were produced to re-create the room's original appearance. The cornice was made according to measured drawings taken from the original, which was left in Baltimore.

As significant pieces of Baltimore furniture have entered the collection, they have found their way into this room. For example, one of the card tables on view came to the Museum in 1932, the remarkable sideboard with knife box was purchased in 1945, and the set of chairs and a second card table were given to the American Wing in 1971.

Image: The Baltimore Room in the 1950s, after acquisition of the card table but prior to the arrival of the set of chairs now on view

Rethinking the Baltimore Room

The room's appearance today reflects the curatorial choices made during a 1980 reinstallation. This campaign relied on muted colors for the walls, but analysis of the woodwork has since revealed that the room originally featured a complex scheme of putty, tan, and dark blue-gray. Furthermore, wallpaper originally covered the area above and below the chair rail.

We also now know that carpeting was widely used in parlors and dining rooms in the early nineteenth century, but the floor in the Baltimore Room has been left exposed save a reproduction oilcloth from the 1980 installation. In actuality, an oilcloth like this would have been used to protect an expensive carpet from spills, not a bare floor.

Elegant furnishings from home and abroad

As Baltimore's economy flourished in the late eighteenth century, an active community of artisans developed there. Skilled cabinetmakers provided local merchants with elegant furniture designed in the Neoclassical style with the help of pattern books published in London. Their tables, chairs, and sideboards, accompanied by imported ceramics and glassware as well as luxury wares from Baltimore silversmiths, filled the parlors and dining rooms of the city's chic brick row houses.

Image: Attributed to Dihl et Guérhard (French, 1781–ca. 1824). Covered tureen, ca. 1800–1815. Porcelain, 10 1/4 x 15 5/8 x 7 3/4 in. (26 x 39.5 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Solomon Grossman Gift, in memory of Berry B. Tracy, and The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift, 1994 (1994.480.1a, b)

Partial table service

Partial table service, 1918. London. Blown cut glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, William Cullen Bryant Fellows Fund, 2008 (2008.594.1-.53)

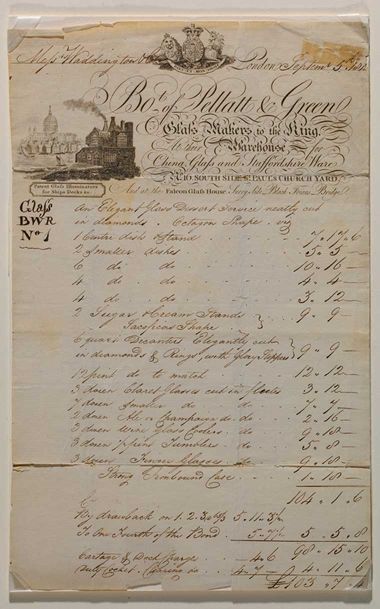

William Bayard (1761–1826) commissioned this table service in 1818 for his daughter Harriet (1799–1875) and her husband Stephen Van Rensselaer IV (1789–1868) from Pellatt & Green, London's premier glasshouse. The fine lead glass and deep Regency cutting would have created a brilliant sparkle in their candlelit dining room in Albany, New York. The set originally included dozens of drinking glasses for claret, ale, and champagne, as well as decanters, wine coolers, tumblers, and finger glasses—all "elegantly cut in diamonds & Rings" according to the surviving bill of sale. In addition to its elegance and quality, the service is extremely rare in its documentation of the specific American family that owned it and to the English glasshouse that made it.

Image: Bill of sale, Pellatt & Green, September 5, 1818. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, William Cullen Bryant Fellows Fund, 2008 (2008.594.54a, b)

Patriotic porcelain

Attributed to Dihl et Guérhard (1781–ca. 1824). Partial dinner service, ca. 1800–1815. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Solomon Grossman Gift, in memory of Berry B. Tracy, and The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift, 1994 (1994.480.1a, b-.16)

This dinner set was manufactured in Paris, but it was clearly intended for the American market. It originally contained more than 125 pieces, including dinner and soup plates, sauceboats, tureens, platters, serving dishes, and butter dishes on stands. Motifs such as the Native American figure and the American flag would have appealed to patriotic customers celebrating the United States' emergence as a powerful nation. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, James Monroe, and other prominent statesmen and diplomats purchased French porcelain services of this kind.

Left: Detail of lid covered tureen with Native American figure. Right: Detail of plate with American flag.

Left: Detail of lid covered tureen with Native American figure. Right: Detail of plate with American flag.

Cruet stand

Very few American-made cruet stands are known from the early nineteenth century. The firm of Harvey Lewis and Joseph Smith had a reputation for high quality work; this example is distinguished by its restrained elegance and artful craftsmanship. The glass bottles are not original to the stand.

Very few American-made cruet stands are known from the early nineteenth century. The firm of Harvey Lewis and Joseph Smith had a reputation for high quality work; this example is distinguished by its restrained elegance and artful craftsmanship. The glass bottles are not original to the stand.

Image: Lewis and Smith (active ca. 1805–11). Cruet stand, ca. 1805–11. Silver, 9 3/4 x 8 5/8 x 7 in. (24.8 x 21.9 x 17.8 cm); 20 oz. 14 dwt. (643.5 g). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Geoffrey N. Bradfield, 1983 (1983.441)

Set of 12 side chairs

Left: Possibly by Henry Ingle (American, 1763–1822). Side chair (one of twelve), 1795–1810. Washington, D.C.. Mahogany with oak, tulip poplar, yellow pine, maple, 36 3/4 x 20 x 20 in. (93.3 x 50.8 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Flora E. Whiting, 1971 (1971.180.16-.27). Right: Plate from George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788)

Furniture historians debate whether this set of chairs originated in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, or South Carolina. Although the molded front legs, stretchers, and serpentine-front saddle seats are more frequently found in Philadelphia seating furniture, the secondary woods used in the seat frame—yellow pine and oak—are more typical of a southern locale. Recent research suggests that they were made by craftsmen working in the Washington, D.C. area.

The design of this chair's back was taken directly from George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788). Carved chairs with upholstery over the rail were formal enough for a parlor setting, but the durable horsehair cover made them suitable for use in the dining room as well.

Pair of drop-leaf dining tables

Left: Drop-leaf dining table (one a pair), 1795–1810. Baltimore. Mahogany, holly with tulip poplar, white pine, sycamore, 28 1/2 x 47 7/8 x 39 1/4 in. (72.4 x 121.6 x 99.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919 (19.13.1, .2). Right: Much of the detail of the marquetry eagle was lost through refinishing before the Museum acquired the table

Large, two- or three-piece dining tables came into vogue in the United States toward the close of the eighteenth century, as wealthy American householders were more frequently dedicating a specific room to formal dining. However, unlike a bulky sideboard that tended to remain in one location, a dining table with drop leaves could be conveniently stored against the wall when not in use.

The inlaid eagle in an oval reserve seen at the top of each table leg is a motif common to Baltimore furniture in the Neoclassical style. Although sometimes imported from England, these marquetry panels were also made locally and conveyed a sense of patriotism during the early decades of American independence.

Sideboard

Sideboard, ca. 1795–1805. Middle Atlantic states. Mahogany, satinwood, silver, copper, verre églomisé with yellow poplar, white pine, mahogany, 65 1/2 x 89 x 31 in. (166.4 x 226.1 x 78.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest and Mitchel Taradash Gift, 1945 (45.77)

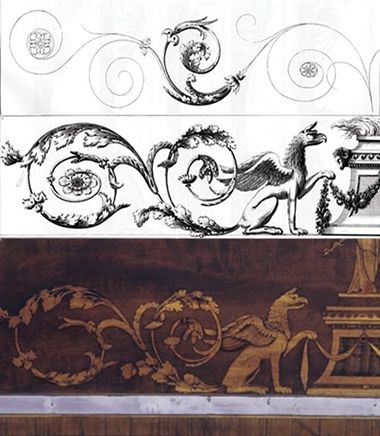

Unknown in American homes prior to the late 1790s, the sideboard quickly became an essential component of the fashionable dining room. It provided space for the storage and display of expensive silver flatware, porcelain, and glassware used during the course of a meal. This massive and resplendent example with an accompanying knife box is a tour de force of early-nineteenth-century cabinetmaking. It includes a unique variety of ornament, from inlaid panels of mahogany veneer, marquetry, and silver-plated copper to verre églomisé.

Many of the motifs found in the sideboard's panels of marquetry and verre églomisé were taken directly from Thomas Sheraton's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-Book (1793). Sheraton (1751–1806), an English cabinetmaker and drawing instructor, influenced numerous American furniture manufacturers through this publication, which was imported all along the eastern seaboard.

Image: Drawing from Thomas Sheraton's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-Book (1793) and detail of marquetry panel

Card tables

Left: Card table, 1790–95. Baltimore. Mahogany, satinwood, sycamore, holly with oak, yellow poplar, 28 1/2 x 34 1/2 x 16 in. (72.4 x 87.6 x 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, 1932 (32.55.4). Right: Card table, ca. 1800. Baltimore. Mahogany, satinwood, holly with white pine, sycamore, birch, 30 3/4 x 35 x 17 1/4 in. (78.1 x 88.9 x 43.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Flora E. Whiting, 1971 (1971.180.50)

Card tables are more typically associated with parlors and sitting rooms, but these lightweight and versatile objects lent themselves to a variety of activities, from taking tea to conducting correspondence.

Although not a pair, these two card tables are similar in form and ornament, both featuring distinctive Baltimore bellflower inlays on their legs. Set into satinwood panels on all four legs, the connecting ring at the top of the bellflower string is typical of the Baltimore style.

The card table pictured at the left and its mate, now in a private collection, were produced en suite with a Pembroke table that would have been used for informal meals not requiring a large dining table.

Pair of looking glasses

This looking glass bears motifs characteristic of the work of the Scottish architect Robert Adam (1728–1792), such as paterae, urns, bellflowers, and fans. It reflects the Neoclassical taste that swept the United States after the revolution.

Image: Looking glass (one of a pair), 1795–1810. Boston. Gilded gesso, verre églomisé with white pine, wire, 50 1/2 x 31 in. (128.3 x 78.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1956 (56.46.1)

Chandelier and pair of sconces

Left: Chandelier, 1795–1810. British. Colorless, opalescent and amethyst glass, gilt bronze, H. 40 in. (101.6 cm); Diam. 22 1/2 in. (57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1968 (68.177.1). Right: Candelabrum (one of a pair), 1795–1810. British. Colorless, opalescent and amethyst glass, gilt bronze, H. 29 in. (73.7 cm); Diam. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1968 (68.177.3)

This chandelier and matching sconces were purchased by Thomas Cornell Pearsall (1768–1820), a New York merchant. They are surviving examples of imported English lighting devices from the turn of the nineteenth century. In that era, chandeliers were occasionally seen in American public places such as theaters, churches, and assembly rooms but were only rarely found in domestic settings. American glass manufacturers were producing chandeliers by the 1810s, but Pearsall, one of the wealthiest men in New York City, surely imported these extraordinary examples from London. Chairs and a sofa once belonging to Pearsall are on display in the Richmond Room.

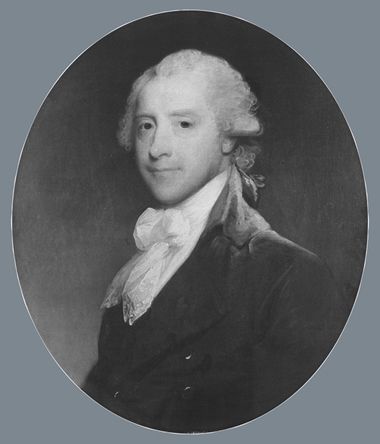

Portrait of William Kerin Constable

Born in Dublin, William Kerin Constable (1753–1803) immigrated to America and settled in New York, where he engaged in the international trade that dominated Baltimore's burgeoning economy. In 1784 he became a founding partner of the firm Constable, Rucke and Company, which outfitted the first American vessel to trade with China and India. The Chinese-export porcelain jars displayed on the sideboard reflect the type of luxury goods that Constable would have imported.

Image: Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828). William Kerin Constable, 1796. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 1/2 in. (72.7 x 59.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Richard De Wolfe Brixey, 1943 (43.86.2)

Portrait of Mrs. Andrew Sigourney

Elizabeth Williams (1765–1843) was the eldest daughter of Elizabeth Bell and Henry Howell Williams. In 1797 she married Andrew Sigourney, a prominent Bostonian. Over the course of his life, Sigourney served as a treasurer of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, treasurer of the town of Boston, and representative in the Massachusetts state legislature. Here, Stuart Gilbert has toned down the almost sensual quality he lent many female sitters in order to emphasize Mrs. Sigourney's knowing intelligence and prosperity.

Image: Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828). Mrs. Andrew Sigourney, ca. 1820. Oil on canvas, 27 x 22 in. (68.6 x 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Donald F. Bush, in memory of Harriet P. Bush, 1978 (1978.380)

Still life paintings

Left: John Woodside (American, 1781–1852). Still Life: Peaches and Grapes, ca. 1825. Oil on wood, 9 3/4 x 12 1/4 in. (24.8 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1941 (41.152.1). Right: John Woodside (American, 1781–1852). Still Life: Peaches, Apple, and Pear, ca. 1825. Oil on wood, 9 3/4 x 12 1/4 in. (24.8 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1941 (41.152.2)

John Woodside probably received his training from Philadelphia sign painter Matthew Pratt or one of Pratt's business partners. In 1805, Woodside opened his own studio in Philadelphia, advertising his services as an ornamental or sign painter. He aspired to less mundane genres, however, and tried his hand at emblematic and patriotic works, animal scenes, miniatures, and copies after English engravings. From 1817 to 1836 he exhibited still lifes and animal pictures at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

These companion still life paintings, Still Life: Peaches, Apple, and Pear and Still Life: Peaches and Grapes, are among Woodside's few known still lifes and represent his best efforts as a painter. His arrangement of peaches and grapes in a spare setting bears the stylistic imprint of the Peale family, which established a still-life tradition in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century.

American Federal-Era

Period Rooms

The three decades that followed the formation of the United States are referred to as the Federal era in recognition of the early development of the national government.

Post-Revolutionary America: 1800–1840

The United States became a continental nation with the purchase of Louisiana from France in 1803 and the settlement of the lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains.