Frank Lloyd Wright Room

Living Room from the Francis W. Little House, Wayzata, Minnesota, 1912–14

Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts

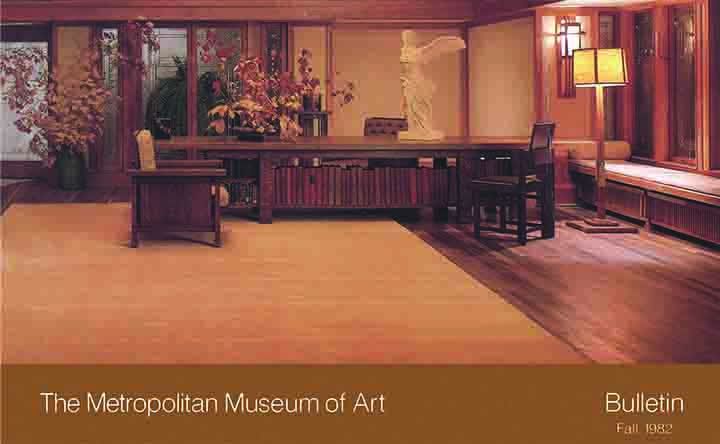

The Living Room from the Francis W. Little House, installed in Gallery 745 in the American Wing, was the center of family activity in one of Frank Lloyd Wright's grandest homes in the Prairie School style. Built for lawyer and businessman Francis W. Little and his wife, Mary, the summer retreat overlooking Lake Minnetonka embodied Wright's comprehensive architectural vision. Working closely with his clients, Wright designed every element of the house, including the furniture, windows, and light fixtures. Together, Wright and the Littles created an interior that is expansive yet cozy, angular yet welcoming, global in its influences yet deeply rooted in the local landscape.

An alternate view of the living room showing the fireplace along the far wall

Origins of the Prairie School Home

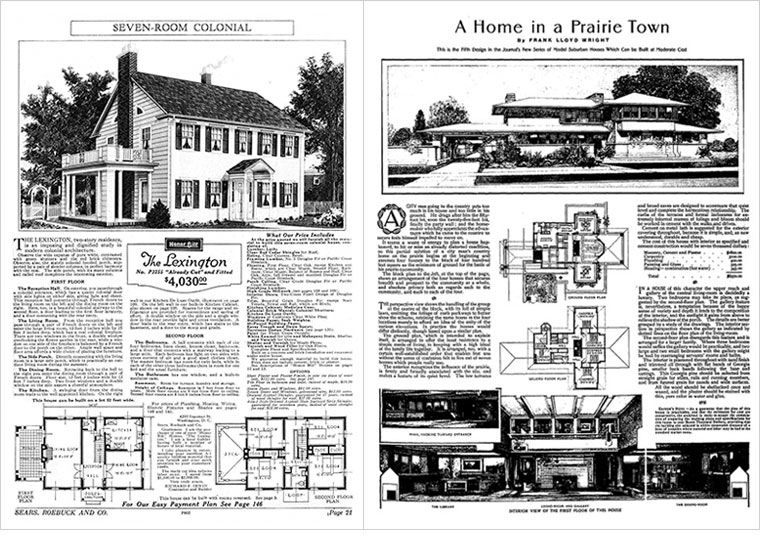

Left: Sears, Roebuck and Company plans for a typical Colonial Revival house, ca. 1920. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright's design for "A Home in a Prairie Town," The Ladies' Home Journal, February 1901.

In the early twentieth century, Frank Lloyd Wright and other Chicago-based architects such as Wright's mentor, Louis Sullivan (1856–1924), and contemporaries George Washington Maher (1864–1926) and George Grant Elmslie (1869–1952) began to reconsider the underlying assumptions about traditional domestic architecture and to design homes suited to the daily routines of modern American families. While then-popular Colonial Revival style houses featured symmetrical layouts with rooms opening off central hallways, Prairie School architects introduced open plans centered on communal gathering areas with fluid transitions from one space to the next. These homes, designed from the inside out, functioned as organic units.

Characteristics of the Prairie School Home

The Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois, 1909–10

Prairie School architects drew inspiration from the rolling plains of the Midwestern landscape. Wright and his contemporaries envisioned low-lying structures that expanded across sites in response to the landscape's natural features. Long hipped roofs, horizontal bands of leaded-glass windows, and wide porches echoed the region's uninterrupted horizons and helped to integrate interior and exterior spaces. Wright and his colleagues gravitated toward minimally treated building materials in colors derived from nature to further incorporate houses into their surroundings.

The Littles' house in Peoria, Illinois

The Littles' first home designed by Wright, Peoria, Illinois, 1902–3

The Littles first hired Wright to design their home in Peoria, Illinois, which he completed in 1903. Wright designed the brick house in the classic Prairie School style and also provided furnishings for the home. A large covered porch extended from the front of the house, and Wright also designed a garage and stable on the property. The Littles lived in the house for only about a year before financial problems forced them to sell it. When they left, they took with them some of the furniture that Wright had designed for it.

Wayzata House, exterior and interior

Exterior of the Littles' Wayzata, Minnesota, house soon after it was completed

The Littles moved to Minneapolis in 1907 and once again contacted Frank Lloyd Wright, asking him to design a new summer home for them. Wright envisioned the Littles' new house as a series of largely self-contained pavilions positioned in a cruciform arrangement. The house stretched 250 feet along the shore of Lake Minnetonka, following the contours of two hills. Wright allotted public and private areas according to the undulating topography: the living room was perched on the crest of a hill overlooking the lake, the bedrooms were a step below, and the service areas such as the kitchen were positioned at the hill's base.

Living spaces

Approach to the house, ca. 1914–15

Visitors approached the home by a winding gravel path and ascended a monumental staircase to the front door. Entering through a small, low vestibule and turning left, guests emerged into the graciously proportioned living room lit by bands of leaded-glass windows lining the two long facing walls. Banks of built-in seating, wrap-around ledges, and oak trim accentuate the room's length, while a patterned-glass light fixture running nearly the length of the ceiling draws attention upward. An imposing fireplace composed of the same elongated bricks used for the exterior of the house anchors the room's north end.

Windows

Living room windows with the view over Lake Minnetonka, ca. 1914–15

Frank Lloyd Wright is justly famous for the intricate leaded-glass windows he designed for his Prairie School houses. In the Littles' living room, he created a symmetrical series of abstract geometric patterns for the twelve windows on each side and repeated the motif in the upper clerestory windows and on the doors at either end. At Francis Little's request, Wright modified the patterning, reducing the areas of leaded glass in the windows as they neared the center of the room, where the Littles' cherished view of Lake Minnetonka could be admired through large panes of plain glass.

Wright as furniture designer

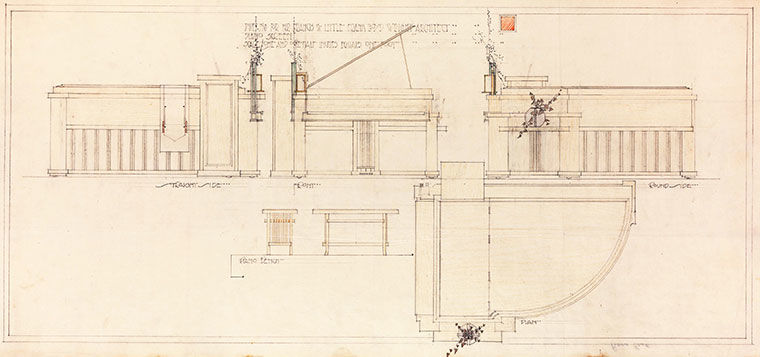

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Billiard table and rail to dining room staircase, ca. 1908–14. Graphite and colored pencil on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.607.5)

Wright often extended his purview as an architect beyond the design of a building to furnishing its interiors as well. Although he commissioned furniture makers such as George Niedecken (1878–1945) to execute his designs, Wright provided plans for furnishings for many of his Prairie School homes, including both of the houses he designed for the Littles. For Wayzata, Wright created drawings for an array of furniture, including a billiard table and cue rack.

Piano case

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Piano screen, ca. 1908–14. Graphite and colored pencil on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.607.6)

Mary Little, a talented pianist, used the living room as a recital space, and the family sometimes referred to the space as the "music room." Wright drew up plans for a decorative wood case for Mary's piano that would harmonize with the other furnishings in the room, but it was not built, probably owing to cost overruns on the entire house project. The piano she used in the room had a traditional nineteenth-century Rococo Revival style case of dark wood embellished with naturalistic carving.

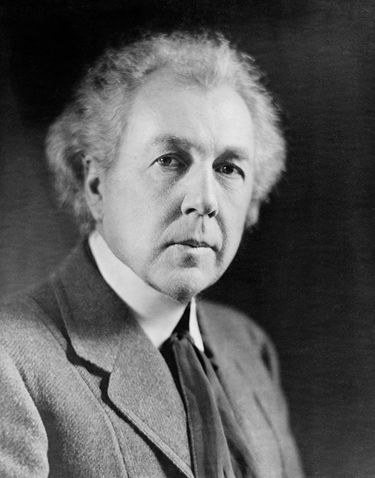

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959): Early career

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in rural Wisconsin to a progressive mother who encouraged him from an early age to be an architect. After completing two semesters of civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin, he moved to Chicago and joined the influential architectural firm Adler and Sullivan in 1887. Wright soon began to design residential commissions for the firm and in 1893 opened his own practice in Oak Park, Illinois, at first focusing almost exclusively on house design.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright, ca. 1925

Frank Lloyd Wright: Turbulent years

Taliesin, Wright's home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, soon after its completion in 1912

The time between 1908, when Wright began planning the Littles' house, and the completion of that residence in 1914, was a period of creative flowering for the architect and of consternation for his clients. In 1909, after leaving his wife and children for the wife of a client, Wright departed for two years of travel in Europe. Despite Francis Little's pleas to Wright to complete their Minnesota summer home, the architect returned to the United States in 1911 only to dive into the construction of Taliesin, his own home and studio in Wisconsin. It wasn't until 1912 that work on the Wayzata house began anew.

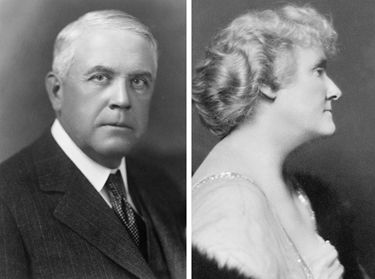

The Little family

Francis W. Little (ca. 1860–1923) and Mary Howard Trimble Little (ca. 1870–1941) were native Midwesterners and lifelong supporters of the region's cultural life. They were founding members of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Mary was an accomplished pianist who had studied in Germany. The living room's design owes much to her desire for a comfortable recital space. The Littles initially hired Wright in 1902 to design their home in Peoria, Illinois. Little was vice president of the Peoria Gas & Electric Company until 1907. That same year, he became vice-president of the Minneapolis Trust Bank and the family moved to Minnesota.

Left: Francis W. Little in an undated photograph. Right: Mary Howard Trimble Little in an undated photograph

An architect and his patrons

Mr. and Mrs. Little on the steps of the Wayzata House soon after it was completed

After the Littles moved to Minneapolis, they purchased property on the shore of nearby Lake Minnetonka and asked Wright which to build them a summer retreat. Francis Little and Frank Lloyd Wright's close yet occasionally fraught friendship survived tense disagreements over design and timeline. Wright's inscription in Little's copy of the architect's Wasmuth Portfolio (1910), prints of his collected works to date that Little helped finance, provides insight on the relationship: "to my client-friend and friend-client" and signed it, "from his problematical Frank Lloyd Wright with real affection nevertheless."

Conflict over window designs

One of the long window walls as installed at the Museum

Tensions between the architect and client came to a head over the design of the living room windows. Little rejected a series of Wright's drawings for them, claiming that they were so overdesigned that they would obscure the lake view. Wright grudgingly simplified the scheme by eliminating most of the central windows' ornamentation and grumbled that the amended form "is not bad of course but rather sterile when something more is needed. I think the one I offered is very much better—but . . . what can I do or say?"

Fostering historic preservation

The Living Room when it was being used for storage, 1972

In the 1960s and 1970s, architectural historians were fighting an uphill battle to preserve iconic examples of American buildings, many of which were being demolished to make way for new construction. The failed campaign to save McKim, Mead, and White's grand, classical New York Pennsylvania Station, which was razed in 1963, catalyzed preservationists, who rallied around remaining examples of important nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings across the country.

After Francis Little died in 1923, his wife, Mary, moved from the main house to the guest cottage on the Wayzata property. After Mary's death in 1941, the Littles' daughter Eleanor Stevenson and her family winterized the main house and moved in full-time. By the early 1970s, they were having difficulty maintaining the large house and eventually closed off the living room, with the majority of the Wright-designed furnishings inside. The rising costs of upkeep and high taxes convinced them to construct a more modest home on the property, but local zoning ordinances required the original residence to be razed before the new project could begin.

Saving a masterpiece

Assistant Curator Morrison Heckscher checking the house plans during the room's dismantling. "N.Y. Museum Begins Disassembly of Wright House in Deephaven," The Minnetonka Sun, May 18, 1972

In 1972, a group of local Midwestern architects and Wright enthusiasts alerted curators at The Met that the house was to be demolished. The Museum agreed to buy it, but the decision to tear the house down and relocate selected interiors was troubling to some. Morrison Heckscher, the curator in charge of dismantling the house, recalls, "I alternated between greedy admiration for that living room and absolute horror at the thought that Wright's house was going to disappear. As a curator, I saw something splendid for the Museum; as an architectural historian concerned with preservation, I saw defeat in demolition."

A house divided

Contact sheet prints of the demolition process, 1972

Over the course of two months, Morrison Heckscher, then an assistant curator, oversaw the labeling, dismantling, and shipment of every element in the living room, brick by brick and board by board. In addition to moving the entire structure and all the contents of the living room to New York, The Met facilitated the shipment of the library to the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania and a hallway to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Preservation dilemmas

The Library from the Little House as currently installed at the Allentown Art Museum. Image courtesy of the Allentown Art Museum

Removing the living room from the Little House in Minnesota and installing it in New York fragmented Wright's comprehensive spatial concept and decoupled the house and its contents from the landscape and topography that was foundational to the architect's design. Yet, The Met's purchase and management of the home and its contents staved off the total destruction of the house and preserved three spaces for millions of visitors to view each year.

Furniture arrangement from a period photograph

The Living Room as arranged by Frank Lloyd Wright for publication in Henry-Russell Hitchcock's In the Nature of Materials (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942), fig. 200B

Most of the furniture on view in the Littles' living room is from their Wayzata home and is original to the room. The installation reflects the interior as it appeared in In the Nature of Materials (1942), Henry-Russell Hitchcock's book on Wright. According to the Littles' daughter Eleanor Stevenson, Wright came to the house before the photo shoot and arranged the room as he wanted it presented in the book, but the family changed the furniture back to their own preferred layout as soon as the session was over.

Furniture arrangement from a floor plan

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1897–1959). Furniture plan (detail). Graphite and colored pencil on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.607.3)

When the house was designed, Wright provided the Littles with a floor plan detailing the type and position of each piece of furniture in the living room. In the drawing, Wright specified more furniture for the room than may actually have been made. Eight side chairs and five tables are depicted in the plan. Leaving the center of the living room largely empty, Wright clustered seating around the periphery to create intimate nooks for reading or conversation. The Museum used this plan as a guide for furnishing the room.

A new kind of period room

View of the Living Room looking south

After nearly a decade in storage, the living room was conserved and reassembled at The Met, and in 1982 it opened to the public. It is one of few period rooms at the Museum that displays nearly all of its original furnishings. Installed across the Engelhard Court from Louis Sullivan's 1893 Chicago Stock Exchange staircases within the Museum, located four blocks south of Wright's late-career masterpiece, the Guggenheim Museum, the Littles' living room links a legacy of Midwestern ingenuity to the bold designs of Wright's mature work. The living room celebrates Wright's signature Prairie School style and his holistic approach to domestic design.

Peoria furniture, 1902–3

The furniture for the Littles' Peoria house (1902–3) was finished with dark brown stain, and the designs incorporated elements of decorative trim, as seen on this print table and armchair

Francis and Mary Little brought several Wright-designed pieces to Wayzata from their home in Peoria, Illinois, such as the living room armchairs, plant stands, table for displaying prints, and large library table. These earlier pieces have a dark-stained finish, and Wright adorned most of them with stylized decorative capitals, bases, and trim.

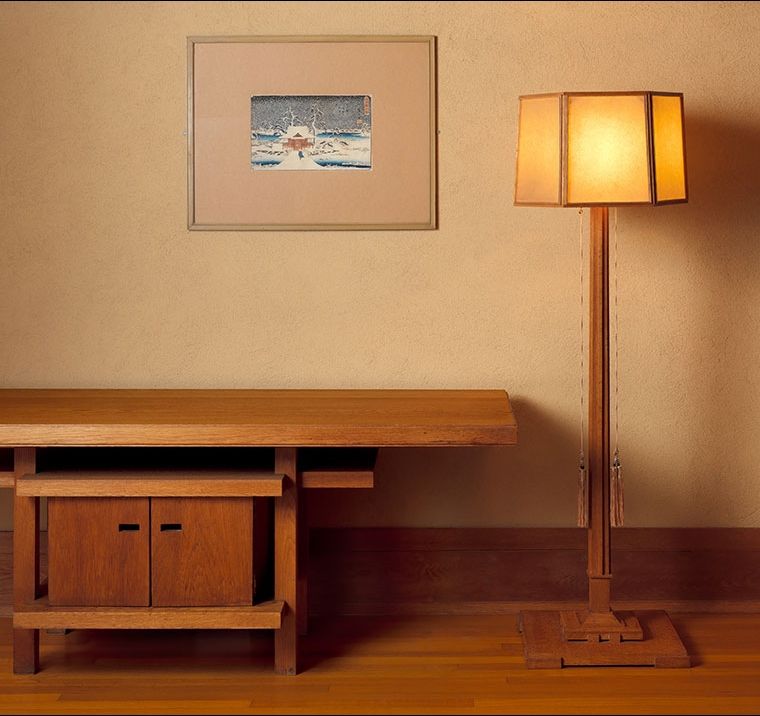

Wayzata furniture, 1912–14

The furniture made for the Wayzata house (1912–14) is lighter in color and simpler in design than the furniture made for the earlier Peoria house

The furniture Wright created specifically for the Wayzata home—light-colored, waxed oak tables, standing lamps, and wall sconces—appears drastically pared down when compared to the earlier Peoria pieces. It is much like the austere furnishings the architect was creating in 1911 for Taliesin, his own home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Wright's later designs, with their balanced geometric components and exaggerated horizontal planes, directly connected to the look and feel of the architecture and environs of the Wayzata house.

Print table

Wright designed this print table as a stock item and used the form in several of his houses. The Littles brought it with them from their earlier home in Peoria, and on it, they exhibited the family's large collection of Japanese prints on it, most of which they purchased from Wright, who was an avid collector and dealer. One or both leaves of the versatile table can fold down to display large prints and portfolios. When the leaves are folded up, items can be stored between them. The covers of Wright's Wasmuth Portfolio (1910) of Wright's designs, a project partially funded by the Littles, are currently displayed on the table.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Print table, 1902–3. White oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.8a,b)

Library table

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Library table, 1902–3. White oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.20)

The large library table that dominates one end of the room was originally made for the Littles' Peoria house, but both ends of the table were extended when it was moved to Wayzata, bringing it to its current length of almost 13 feet. It is a practical piece of furniture, constructed with multiple shelves for holding books of different sizes. As a vertical counterpoint to the low, spreading surface of the tabletop, a plaster reduction of the famous 2nd century B.C. Winged Victory of Samothrace, a sculpture that Wright used in many of his Prairie School interiors, was placed on it.

Table

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Table, 1912–14. White oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.3)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed this table specifically for the Littles' living room in Wayzata, using the same light-finish white oak used in the room's trim, light fixtures, and shelving. The long tabletop appears almost to float above the four sturdy legs, and the central cabinet block seems to be hung from the top. Instead of attaching handles to the cabinet doors, Wright designed simple cut-out handholds. His design marries substantial forms to frame surprising slices of negative space. The overall effect is that of a table that is grounded yet light and seamlessly integrated into its environment.

Two plant stands

These two plant stands were made for the Littles' Peoria house and are identical to a set that can be seen in photographs of the house Wright designed for Susan Dana in Springfield, Illinois (1902). While Wright designed unique, built-in furnishings for many of his domestic interiors, he appears to have created a standard set of moveable furnishings to be included in many of his Prairie School style commissions.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Plant stand, one of two, 1902–3. White oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.11,.12)

Four armchairs

This set of four armchairs in dark-stained oak was designed for the Littles' first home in Peoria, Illinois, and moved with the family, eventually ending up in the living room of their new summer home. Unlike Wright's later furnishings (1912–14) in the room, these chairs include decorative applied banding and, on each leg, stylized capitals and bases. The chairs' cushions are covered with their original wool fabric.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Armchair, one of four. White oak, wool. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.4–.7)

Two side chairs

These two chairs were among the Wayzata room's furnishings, however it is not known whether they were designed for it or for the Littles' earlier Peoria house. Although the finish is the darker stain of the Peoria pieces, the sleeker, less ornamented form of the chairs may indicate that they are from the later commission. Other chairs of this same design were made for Wright's 1908 Isabel Roberts House. In the 1942 photograph of the room, two additional chairs like these, but without the leather backrest, are seen drawn up to the print table.

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Side chair, one of two, ca. 1902–3. White oak, leather. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.9–10)

Sofa

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Sofa, 1909. White oak, oak plywood, secondary woods, wool. Lent by the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Gift of the Chicago Theological Seminary (L.1982.125)

Frank Lloyd Wright included a divan (sofa) in his plan for the Wayzata home's furnishings, but what it looked like was unknown until a drawing for it was recently acquired by the Museum (2018.542). Since there was no sofa in the room when it was acquired, this one was borrowed from Wright's Frederick C. Robie House, built in Chicago between 1908 and 1910. Though created a few years earlier than the Little house designs, like them, the Robie house furnishings echoed the horizontal planes of the home's exterior.

Set of standing lamps

Wright designed a set of oak standing lamps for the Littles' summer house on Lake Minnetonka. The shades consist of hexagonal oak frames filled with parchment paper. In a nod to the Asian art that Wright so admired (he made his first of many trips to Japan in 1905), each lamp has a long silk pull cord with a Chinese-style tassel for switching the electric light on and off.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Standing lamp, one of four, 1912–14. White oak, parchment, silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.14-.16,.18)

Four light fixtures

Inspired by the Japanese lantern designs he saw on his first trip to Japan in 1905, Wright fashioned these oak and frosted-glass light fixtures as vertical counterpoints to the horizontal bands of the walls and window banks in the room, the long horizontal shelves at the upper perimeter, and low built-in benches on either window wall.

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Light fixture, one of four, 1912–14. White oak, glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.21–.24)

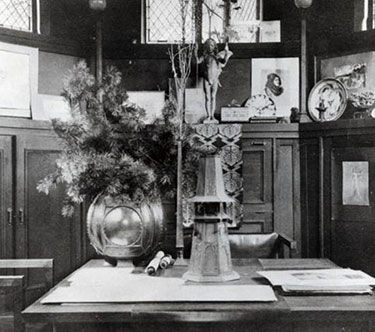

Ceramics, metalwork, and decorations

In designing the furniture for the Little House, Frank Lloyd Wright decorated it with a variety of small objects. The ceramics, metalwork, plaster-cast sculpture, and small carpets in the room are not original to the house but resemble objects that were owned by the Littles. From the 1890s on, Wright collected Japanese prints and Asian objects, some of which he later sold to his clients. The Asian ceramics on the clerestory shelf did not belong to the Littles, but the Japanese prints have always been in the room and were perhaps acquired by the Littles from Wright.

Image: Urn and "weed holder" in Wright's Chicago studio. Note the high shelf for displaying ceramics and other artistic objects. The Architectural Review, June 1900, p. 65

Vase

When selecting American-made ceramics for his interiors, Wright gravitated toward geometric silhouettes in muted matte glazes such as those produced by the Grueby Faience Company. Popular among early twentieth-century American Arts and Crafts enthusiasts, Grueby's earthenware pieces and architectural tiles were inspired by Japanese forms and glazed using French techniques. This vase, while not original to the room, is similar to others found in Wright interiors. Wright often designed high shelves around the walls of a room for the display of ceramics and other decorative objects.

Image: Grueby Faience Company (1894–ca. 1911). Vase. Revere, Massachusetts, ca. 1900–10. Earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, in memory of George H. Milne and Louise Porter Milne, 1982 (1982.49)

Vase

Teco Pottery was a favorite among Prairie School style architects, several of whom, including Wright, designed wares for the company. The studio specialized in organically inspired shapes in neutral tones that were ideally suited to Prairie Style interiors. This oversized vase was marketed as a container for umbrellas and walking sticks. In a letter from 1981, the Littles' daughter Eleanor Stevenson remembered that a large Teco vase like this one occupied a spot by the room's entrance.

Image: Designed by William Day Gates (American, 1852–1935) for the Teco Pottery Company (ca. 1890–ca. 1927). Vase. Terra Cotta, Illinois, ca. 1901–22. Earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Theodore R. Gamble Jr., in honor of his mother, Mrs. Robert Theodore Gamble, 1982 (1982.188)

Fern dish

Metalsmith Karl Kipp created this fern dish at Roycroft, an Arts and Crafts community in East Aurora, New York. Roycroft's founder, Elbert Hubbard, marketed a variety of books, furniture, leather goods, and metalwork inspired by the British Arts and Crafts Movement. Although the Littles did not own a fern dish just like this one, the room was furnished with several low bowls for holding arrangements of flowers and leaves, reflecting Wright's belief in bringing nature into the home.

Image: Designed by Karl Kipp (American, 1882–1954) for Roycroft (1895–1938). Fern Dish. East Aurora, New York, ca. 1911. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Theodore R. Gamble Jr., in honor of his mother, Mrs. Robert Theodore Gamble, 1982 (1982.118)

"Weed holder" vases

Wright designed these copper vases that he called "weed holders" and displayed them in his own home in Oak Park, Illinois, as well as in several other of his residential commissions. While this pair is not the set the Littles owned, their daughter Eleanor Stevenson, in a letter to the Museum dated January 1974, described some of the room's original furnishings and sketched a similar vase, characterizing it as "excessively tall." She wrote that the family had a pair of such vases placed "in the recesses of the fireplace."

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Two vases, ca. 1890–1910. Copper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Charles L. and Jane D. Kaufmann, 1985 (1985.212.1,.2)

Urn

The first example of this Wright-designed copper urn dates from the late 1890s. The form appeared in photographs of at least nine of Wright's Prairie School style interiors, including his own Oak Park studio. The Littles owned one of these urns, and, according to a 1974 letter from their daughter Eleanor Stevenson, "it sat on the ledge over the door going from the music room to the rest of the house." This would have been the door to the left of the fireplace. Since Mary Little's piano stood in this room, the family called it the "music room."

Image: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1862–1959). Urn, ca. 1899. Copper. Courtesy of the American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation, 2011 (2021.267)

Frank Lloyd Wright at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Period Rooms in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A Walk Through the American Wing

The American Wing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 30, no. 6 (June–July, 1972)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide, available in ten additional languages:

español,

русский,

português,

한국어,

日本語,

italiano,

Deutsch,

français,

简体, and

عربى

Keep Learning

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959)

Discover more about the life and work of Frank Lloyd Wright in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Frank Lloyd Wright at The Metropolitan Museum of Art": The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 40, no. 2 (Fall, 1982)

A Met Bulletin by Edgar Kaufmann Jr. featuring an introduction from R. Craig Miller and an essay from Julia Meech-Pekarik.