Gothic Revival Library

Balmville, Newburgh, New York, 1859

Moira Gallagher, Research Associate; and Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts

This library, on view in Gallery 740, comes from a red-brick Gothic Revival villa built for banker Frederick Deming (1787–1860) and his family in the hamlet of Balmville, a residential area in the southeastern section of Newburgh, New York. Designed by British-trained architect Frederick Clarke Withers (1828–1901), the house, later referred to as Morningside, is a classic example of the Gothic Revival style in domestic architecture. The room is arranged to illustrate how an upper-middle-class family might have furnished their library. Printed plates in contemporary design manuals that promoted the use of the Gothic Revival style guided the selection and placement of the furnishings on view, none of which are original to the room.

Newburgh, New York

View of the Hudson River near Newburg [sic]. Published for Herrmann J. Meyer, ca. 1855. Library of Congress

Situated about seventy miles north of Manhattan on the west side of the Hudson River, nineteenth-century Newburgh was a prosperous town. The increased shipping of raw materials and manufactured goods along the river contributed to the city's continued development during the 1850s and 1860s. Despite Newburgh's industrial growth during this period, the southeastern suburban enclave of Balmville became a popular country retreat for wealthy New Yorkers attempting to escape the overcrowding and unhealthy conditions of summers in the metropolis. Their newly constructed spacious country houses, or villas as they were known in the period, offered sweeping views of the Hudson River and the surrounding rolling fields and hills.

The picturesque landscape

This illustration of the ruins of Tintern Abbey, a twelfth-century monastery in Tintern, Monmouthshire, Wales appeared in William Gilpin's Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty…(1782). Gilpin's book was one of the most influential eighteenth-century sources that explored the concept of the picturesque.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, as part of the emerging Romantic sensibility of the time, three aesthetic ideals were introduced and debated. Philosophers and artists attempted to define what should be described as visually beautiful, as picturesque, and as sublime. By the mid-nineteenth century in the United States, these concepts were widely applied to landscape and architectural design. The beautiful landscape was regular, with smooth and gentle curves, while the sublime was vast, overwhelming, and even frightening, such as a high stony mountain range. The picturesque was in between these two; it was irregular and rustic, with visual contrasts between landscape features. Newburgh, New York, with its combination of rolling hills and pastures, paired with the dramatic craggy river banks of the Hudson River, embodied the picturesque American landscape.

In his seminal publication The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), the United States' leading architectural theorist Andrew Jackson Downing mused, "It is in such picturesque scenery as this [the Hudson valley]—wherever, indeed, the wildness or grandeur of nature triumphs strongly over cultivated landscape—but especially where river or lake and hill country are combined—it is there that the highly picturesque country house or villa is instinctively felt to harmonize with and belong to the landscape." As a lifelong resident of Newburgh, Downing was intimately familiar with the beauty of the Hudson River valley.

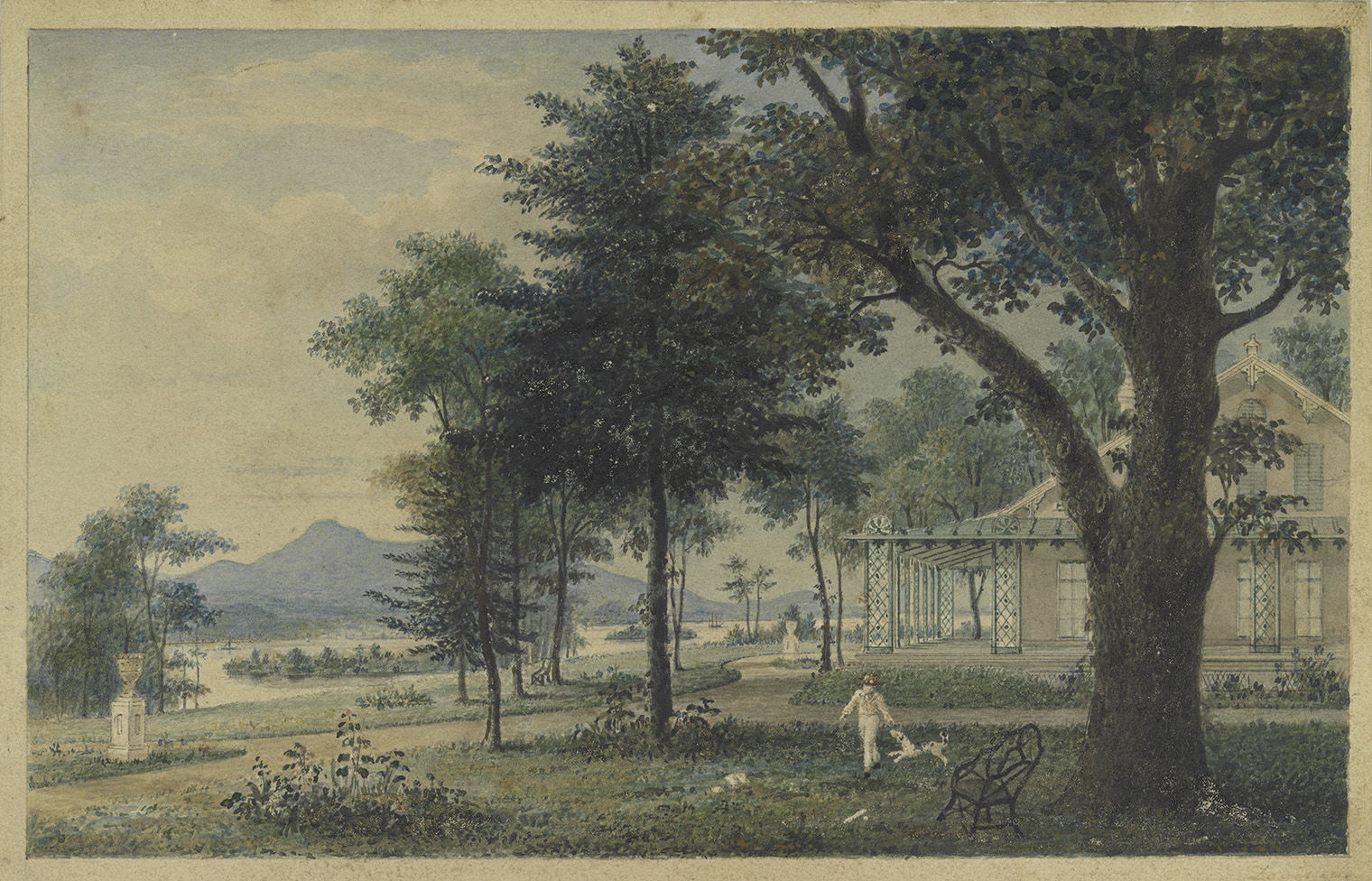

Exterior of the house

Exterior of the house, then owned by the Forsyth family, ca. 1885. American Wing curatorial files

Different styles of architecture were thought to be appropriate for beautiful, picturesque, and sublime settings. While a symmetrical and regular Neoclassical house was appropriate to a beautiful landscape, picturesque settings demanded romantic, irregularly massed houses. The Gothic Revival style was considered especially well-suited to picturesque landscapes.

The house Frederick Clarke Withers designed for Frederick Deming, in which the library originally stood, reflects this preference. Still extant today, it is a bold yet graceful, two-and-a-half-story red-brick structure. The facade is asymmetrical, and broken into four distinct sections that are of different depths and detailing. The sharply peaked roofline is decorated with boldly carved verge boards (the pierced decorative boards that line the pitched roofline) and alternating stone-and-brick voussoirs top the pointed-arch windows.

The rise of the Gothic Revival style in England

Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill. Image by Chiswick Chap

Between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, the Gothic style dominated European architecture. Defined by its intricate ornament and unprecedented building heights, the Gothic style was most frequently used in cathedrals and religious buildings, as well as in early universities like Oxford and Cambridge. Design elements associated with Gothic architecture include lancet (pointed) arches, soaring spires and towers, flying buttresses, trefoils, quatrefoils, and delicate stained-glass windows. By the late eighteenth century, inspired by the rise of Romanticism, and the new literary form of the Gothic novel, including Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley, the Gothic Revival style became popular in England and the Continent. The first truly Gothic Revival home can be credited to the vision of Horace Walpole (1717–1797), an antiquarian, politician, and the author of what is accepted to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764). His house, Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, London, England, was built in stages between 1749 and 1776.

Another highly influential proponent of Gothic Revival architecture was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852), a prominent English architect, designer, and theorist, best known as one of the architects of the English Houses of Parliament (built 1840–76). A devout Catholic, Pugin believed that the use of the decorative vocabulary and techniques of Gothic cathedrals in contemporary architecture and design could serve as a moral corrective for society in the face of industrialization. Not all proponents of the Gothic Revival embraced its religious undertones, but most found its moral aims worthy of promotion.

Westminster Palace, which contains the Houses of Parliament, London, England. Designed by Charles Berry and Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin

The Gothic Revival Villa in the United States

In the United States, the Gothic Revival style was commonly used for churches, such as Grace Episcopal Church (1843–46) and Saint Patrick's Cathedral (1858–1879) in New York City, both designed by James Renwick Jr. (1818–1895). It soon became the favored style of academic buildings and museums—in fact The Met's first permanent home in Central Park was built in the Gothic Revival style. It was also increasingly the preferred style for country houses, popularized in large part by American architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892), who collaborated with Andrew Jackson Downing on his influential book, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850). One of Davis’s earliest domestic projects in this style was Knoll, a distinguished Gothic Revival residence located in Tarrytown, New York built for former New York City mayor William Paulding (1770–1854). The house was later expanded by Davis for New York businessman George Merritt (1807–1873) and renamed Lyndhurst.

Image: Alexander Jackson Davis (American, 1803–1892). Knoll for William and Philip R. Paulding, Tarrytown (south and east [front] elevations), 1838. Watercolor and ink on paper, 11 x 8 in. (27.9 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.66.70)

Different house styles were meant to signal the lifestyle and values of their owners. The Gothic Revival villa was not meant to have overtly religious undertones. It referred more to the ancient centers of learning rather than to the church. As Downing wrote in The Architecture of Country Houses, "The prevailing character of the Grecian and Italian styles partakes of the gay spirit of the drawing-room and social life; that of the Gothic, of the quiet, domestic feeling of the library and the family circle. Those who love shadow, and the sentiment of antiquity and repose, will find most pleasure in the quiet tone which prevails in the Gothic style…" A Gothic Revival house represented a family who enjoyed a quieter, more contemplative lifestyle. In a house like this, the family library often took center stage.

Image: Designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, view facing northwest, 1880

The home library in the mid-nineteenth century

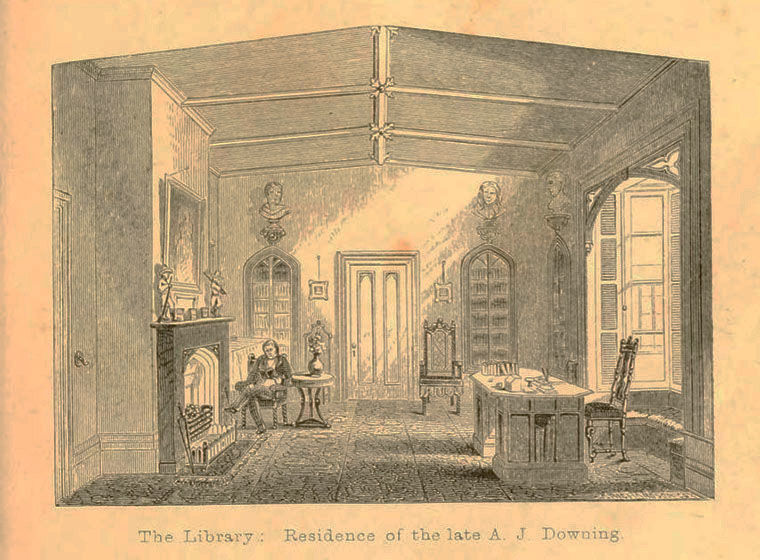

Andrew Jackson Downing in his library at "Highland Garden." Frontispiece from Rural Essays (1853) by Andrew Jackson Downing, published posthumously.

The Gothic Revival style was thought to be particularly appropriate for the decoration of domestic libraries. Houses that were not Gothic in style on the exterior frequently had libraries decorated in this style, which was intended to be reminiscent of scholarly preserves such as medieval monasteries and universities.

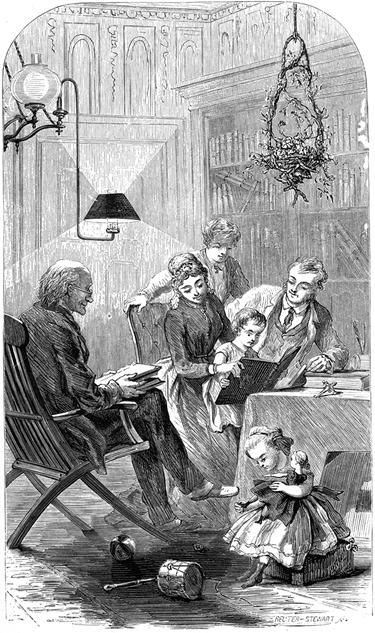

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, private libraries were often the exclusive domain of wealthy gentlemen with academic interests, but by the mid-nineteenth century, the mechanized production of inexpensive cloth-bound books had brought the possession of a good library within reach of most middle-class families. Less formal than the drawing room, the library became the family sitting room, a place where relaxation and even coziness were encouraged.

In 1852, noted author Clarence Cook published a description of Andrew Jackson Downing's Newburgh residence that illustrates the library's ideal function in the middle-class home: "The library is a cheerful and delightful room… On the west side is a large bay window, and in front of it stands the spacious table at which Mr. Downing wrote. In the winter the family forsook the fine south room, which on account of its size was not easily warmed, and lived in the library, which, with its cheerful fire and books and busts, became the gathering point of the household, and the chosen seat of the winter’s evening mirth and daily study."

Image: Frontispiece from The American Women's Home (1869) by Catharine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Interior of the house

View of the Gothic Revival Library

Upon entering the front door of the Deming house, one passed through a vestibule, and then into a large central hall with flooring of multicolored Minton tiles imported from England. The library was immediately to the right, the dining room to the left, and the drawing room straight ahead. The kitchen and servants' wing were farther to the right, past the dining room. The upper stories contained bedrooms.

Withers enlivened the somewhat somber design of the library by creating a play of contrasting colors in the room's woodwork. The floor is striped in alternating oak and walnut boards, and the room's wainscoting is walnut with lightly colored chestnut panels. The original paint scheme that was reproduced in the room features tan painted plaster walls accented with dual dark red pinstripes that trace the profile of the paneling. There is a decorative border beneath the deep ceiling cornice of stylized red ivy leaves alternating with gold leaf bellflowers, which was exactly replicated from the house, as was the elaborate plaster rib and medallion ceiling. The bay window and window seat, which originally looked east over the Hudson River, are set off by trefoil tracery within a wide lancet arch.

Image: Detail of the stylized red ivy leaf border and medallion ceiling, as found in the house. American Wing curatorial files

Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852)

Newburgh was the lifelong home of Andrew Jackson Downing, the United States' leading nineteenth-century architectural theorist and landscape designer. Downing began his career running a plant nursery that he inherited from his father. Not content to simply provide plant material and landscape the grounds of the local gentry, in 1841 at the age of twenty-six, he published A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. This publication, which went through three re-printings, gained him a wide audience. Just one year later in 1842, he published his first book on architecture called Cottage Residences. He often collaborated with American architect Alexander Jackson Davis who created building designs and illustrations for Downing's various publications, which promoted his belief that, "all beauty is an outward expression of inward good." Downing also published a periodical called The Horticulturist beginning in 1846 that expounded on both plants and buildings, and in 1850 produced what was to become his best-known book, the architectural manual The Architecture of Country Houses, which extensively featured Davis's designs. Yet Davis's own career soon took precedence over his work with Downing.

Image: Portrait of A. J. Downing. Frontispiece from his A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening… (1859 edition). Columbia University Libraries Online Exhibitions.

In 1850, when Downing decided to set up his own architectural studio in his Elizabethan-style Newburgh home, Highland Garden. However, there were very few trained American architects at this time for him to work with. While traveling in Britain that summer, Downing, who was a theorist, not an architect, convinced London-trained architect Calvert Vaux (1824–1895) to join him in the United States. Two years later he recruited another young Englishman, twenty-four-year-old Frederick Clarke Withers (1828–1901), to join them in the practice as their architectural assistant. Withers arrived in Newburgh in February 1852. The collaboration was short-lived, as Downing died in a steam boat accident only five months after Withers's arrival. Newburgh served as an incubator for the Downing's lofty ideals, and the numerous private residences and public buildings in the area that survive today, either of his own design or the designs of his collaborators, document his ambitious vision for American architecture.

Andrew Jackson Downing, (American, 1815–1852). A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 1841. Illustrations: wood engraving; a watercolor tipped in at front, 9 1/2 x 6 1/16 x 1 7/16 in. (24.2 x 15.4 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.66.361).

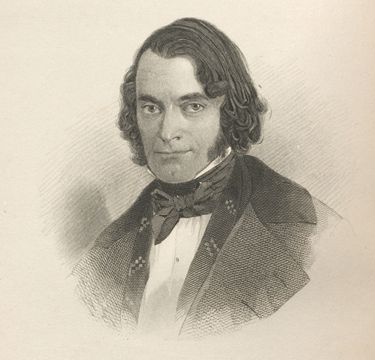

Frederick Clarke Withers (1828–1901)

Born in England and trained in the architectural office of Thomas Henry Wyatt, Frederick Clarke Withers moved to Newburgh, New York, in 1852 to work with Andrew Jackson Downing, who unfortunately died shortly after Withers's arrival in the United States. The young architect then formed a partnership with fellow Englishman Calver Vaux, who had been working with Downing for the previous two years. Vaux and Withers continued the work of their mentor, as well as producing buildings of their own, until Vaux left for New York City in 1856 to begin working with Frederick Law Olmstead (1822–1903) on the design of Central Park. Vaux was also the architect of The Met's first building.

Image: Frederick Clarke Withers, ca. 1861, frontispiece of The Architecture of Frederick Clarke Withers (1980) by Francis R. Kowsky

Withers remained in Newburgh for another ten years, working primarily on private houses. The Deming residence, built in 1859, is one of his early solo works. Although indebted to Downing's theories, its vigor and liveliness reflect Withers's own contribution to Newburgh's architectural landscape. Between 1853 and 1866, Withers completed fifteen houses, four churches, and two banks in Newburgh.

Starting in 1866, Withers established his own practice in New York City. His later work included designs for ecclesiastical and public buildings in the High Victorian Gothic style, notably the Jefferson Market Courthouse (1874–77). Still extant on Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village, New York, it functions today as a branch of the New York Public Library.

Image: One of Withers's best known buildings is the Jefferson Market Courthouse, pictured here. Edmund Vincent Gillion, [Jefferson Market Branch, New York Public Library], ca. 1975. Gelatin silver print. Museum of the City of New York (2013.3.1.591)

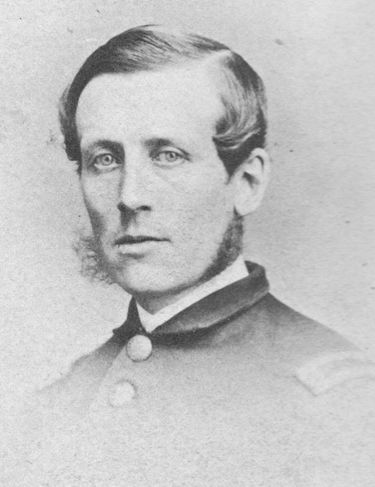

Frederick Deming (1787–1860)

Frederick Deming was born in Litchfield, Connecticut to Julius Deming and Dorothy Champion. In 1813, he married Mary Gleason (1796–1869), and the couple had seven children who survived to adulthood. He moved to New York City and in 1815 started a wholesale dry goods business with his two brothers, Charles and William. He went on to serve as one of the directors of the New York Equitable Insurance Company, and in 1840 he was elected as the president of the Union Bank of New York. While working in New York City, he and his family lived in Brooklyn Heights. Following his retirement from the bank, Deming set about building his new country residence, later known as Morningside, in Newburgh. He died shortly after the house was completed and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. In his will, Deming left the Newburgh residence and $14,000 to develop and maintain the property to his son Frederick Deming Jr. (1832–1925). The will also stipulated that the younger Deming was to allow his mother and unmarried sisters to continue residing at the residence, rent free.

Later owners and occupants

The Deming family retained the Balmville residence until 1868, when the family sold the property to Susan M. Fraser, who in turn sold the property the following year to Robert A. Forsyth (1814–1873) and his wife Charlotte Williams (1815–1893). It descended in the Forsyth family, passing to the couple's daughter Mary Forsyth Wickes (1847–1933).

By the mid-twentieth century, the house had fallen into disrepair, and it was acquired by Senator and Mrs. Thomas Desmond, who lived on the adjacent property but never occupied the house. The Museum purchased the architectural elements of the library and entrance hall from the Desmonds in the 1970s. The house has since been restored and continues to be privately owned.

Image: The exterior of the house, ca. 1987. American Wing curatorial files

Acquiring the room

Looking into the Gothic Revival Library, Gallery 740

In 1977, a curator from the American Wing approached the Desmonds about acquiring one of the rooms from the then-derelict house. When permission was granted, a team of curators, as well as an architect and a master carpenter, was dispatched to Newburgh. After some discussion, it was decided that the most aesthetically and historically interesting room in the house was the library. It was subsequently dismantled and each piece labeled for eventual reinstallation at the Museum, which occurred about ten years later in 1987.

In addition to the library, the colorful and durable English Minton ceramic tile floor from the center hall was removed so that it could be installed in the vestibule to the room at the Museum. This entryway, it was decided, would replicate on a somewhat larger scale the front door vestibule at Morningside, which was beautifully painted with trompe l'oeil panels. These panels are reproduced in the room's vestibule at The Met.

As installed at the Museum in 1987, the library from Morningside is unchanged in scale or decorative finishes; however, due to fire codes and its position with the Museum's galleries, visitors cannot enter the room through one of its existing interior doors. The library is now viewed through an enlarged archway, which replaced a full-length window that originally opened onto the house's veranda.

Missing details

A photograph of the library, ca. 1885. American Wing curatorial files

When the Museum acquired the library in 1977, all of the house's mantels had long since disappeared. A photograph of the library taken about 1885 shows that the original mantel and overmantel mirror had already been removed and replaced with elements in a more ornate, contemporary style. The carved walnut mantel now installed in the room is a modern reproduction, copied from an existing library mantel Withers designed in 1856 for the David M. Clarkson house, also located in the Balmville section of Newburgh.

The oak mirror currently above the mantel was designed around 1840 by the architect Alexander Jackson Davis for Knoll (now Lyndhurst), a distinguished Gothic Revival residence located in Tarrytown, New York. The Gothic Revival cast-iron grate was probably made in New York state.

Image: The reproduction fireplace mantel as installed in the Gothic Revival Library.

Furnishing the room

View of the Gothic Revival Library

It is not known how the Demings furnished their library when they began occupying the house in 1859, and none of the original furniture is known to survive. It is quite possible that the room was not decorated solely with furniture and objects in the Gothic Revival style.

At the time the library was installed at The Met, the American Wing curators were looking to showcase each of the popular mid-nineteenth-century revival styles in period rooms that combined decorative arts and architectural elements of the same style. Only the Renaissance Revival Room contains its original furnishings. In the three other rooms—the Greek Revival Room, the Rococo Revival Room, and the Gothic Revival Room—the furnishings on view reflect a well-researched yet hypothetical installation drawn from period inventories, household manuals, periodicals, prints and photographs, and objects from the Museum’s collection.

For the Gothic Revival Library, the curator relied on plates from Downing's and other’s books, as well as on a period illustration and description of Downing's own library (see above under "The Home Library in the Mid-Nineteenth Century"). The furniture in the room ranges in date from the early 1850s to the mid-1860s. The majority of pieces are either oak or walnut and were most likely made by New York City cabinetmakers, though none are labeled or signed.

Draperies and upholstery

This fabric sample at left was reproduced in a terracotta color for the room's draperies and upholstery, as seen on this side chair. Woven sample. British, (ca. 1850). 20 1/2 x 16 1/8 in. (52.1 x 41 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Elinor Merrell, 1987 (1987.141); Side chair, designed by Alexander Jackson Davis. American, ca. 1848. Rosewood, 42 x 18 1/2 x 21 1/2 in. (106.7 x 47 x 54.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1979 (1979.182)

The design of the room's draperies and choice of fabric was also inspired by home building and decorating manuals of the day. Downing’s Architecture of Country Houses (1850) contains a particularly useful chapter entitled "Interior Finishing of Country Houses." In it, he provided guidance such as: "For a better type of curtain, moreens [a type of wool] of single colors—browns, drabs, crimsons, or blues—may be used…" Another extremely helpful English book that featured illustrations of room and curtain designs was John Claudius Loudon's Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture (1833), a source that Downing himself depended on quite heavily and borrowed from for his own publications.

The drapery and upholstery fabric, a wool-and-silk damask in a Gothic Revival pattern, was reproduced from a piece of English fabric produced in the late 1850s. The original fabric is blue, but since the library is decorated in wood and warm paint tones, the fabric was reproduced in a terracotta color. The curtain border was copied from a small piece of trim in the Museum’s collection, which was enlarged in scale.

Some of the seating furniture is covered with leather, reflecting Downing's sentiments that "Leather or morocco makes the best and most appropriate covers for chairs and other furniture for a library." Other objects have been covered with the same fabric as the draperies, since it was usual to have drapes and furniture decorated en suite during the period.

Library table

Library table. American, ca. 1855. Oak, walnut, cherry, poplar, 29 1/4 x 51 3/4 x 33 7/8 in. (74.3 x 131.4 x 86 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Berry B. Tracy, 1979 (1979.484)

This rectangular library table is supported by four legs, each composed of ring-turned, cluster columns, a design element commonly used on the piers of the arcades of Gothic cathedrals. The drawer fronts and skirt are ornamented with trefoil arches. The leather top provided an improved surface for writing. For the installation of the Gothic Revival Library, the curator selected a variety of desk accessories such as cast-metal letter holders with Gothic designs, a glass inkwell, reading glasses, and miscellaneous papers to suggest the professional and personal correspondence that may have occurred at such a tabletop.

Image: Letter holders, inkwell, and reading glasses on view in the Gothic Revival Library.

Center table

Left: Table. American and Italian, ca. 1860. Walnut, marble, 30 1/2 x 30 1/2 x 44 in. (77.5 x 77.5 x 111.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1986 (1986.78); Right: Detail of marble top.

Although the maker of this octagonal table is unknown, it was likely produced in New York after a design by the British architect Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, published in his book Gothic Furniture (1835). Just as the Morningside's library was enlivened by the contrasting colors of various types of wood, this table features an extraordinary Italian specimen marble top composed of brightly colored pieces of marble and other minerals. The tabletop is supported by architecturally inspired flying buttresses that extend from the central support, an excellent example of how Gothic Revival furniture employed features used in buildings during the Gothic period (12th–15th century). Lancet arches and quatrefoils further enhance the base and the skirt of the tabletop.

Bookcases

Left:Bookcase. American, ca. 1855. Oak, pine, 95 1/2 x 60 x 22 in. (242.6 x 152.4 x 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1977 (1977.310.1); Right: Bookcase. American, ca. 1855. Oak, pine, 95 1/2 x 60 x 22 in. (242.6 x 152.4 x 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1977 (1977.310.2)

Bookcases are a key furnishing in any library. The set of bookcases on view in the Gothic Library both feature upper cases accessed by four glass doors with Gothic-style tracery at the top and a frieze of carved oak leaves, punctuated at the center by a blank shield. The interiors have moveable shelves, which can be arranged to accommodate books of various sizes. While these two examples are quite similar in form and decoration, they are not a matched pair and differ in the treatment of their lower cabinet. The bookcase on the left has four doors with lancet arches and simple trefoil tracery. The lower doors of the bookcase on the right feature more elaborate tracery designs radiating from a central blank shield. The use of the blank shield is a reference to the heraldic designs used by European nobility. As was common in the day, plaster busts of famous authors sit atop the bookcases in the room, as indicators of the contents within them.

Armchair

This large armchair captures the exuberant application of medieval architectural elements to traditional furniture forms. The bold trefoil lancet arches, quatrefoils, and the central rose window design on the back splat recall the tracery of stained-glass windows in soaring Gothic cathedrals. These elements are combined with other historic styles, such as its Baroque-inspired twist-turned legs and stiles. This chair was likely made in New York City, the epicenter of cabinetmaking during the mid- and late nineteenth century.

Image: Armchair, John and Joseph W. Meeks (active ca. 1836–59). Mahogany, 53 x 23 x 22 in. (134.6 x 58.4 x 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Musuem of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1985 (1985.189)

Easy chair

This easy chair is part of a suite of Gothic Revival furniture used in the library at "Steen Valetje," the country estate located just outside of Barrytown, New York, built in 1851 for Franklin Hughes Delano (1813–1893) and his wife, Laura Astor (1824–1902). The arches, quatrefoils, and vegetal ornament on the chair's front legs, arm supports, and seat rail reflect a more subtle application of Gothic architectural elements to furniture in the mid-nineteenth century. The chair's deep seat, slightly reclined back, and tufted leather upholstery (a reproduction) offer its sitter a comfortable seating option for reading or other leisurely pursuits.

Easy chair, American, ca. 1852. Walnut, ash, 43 5/8 x 27 1/2 x 34 in. (110.8 x 69.9 x 86.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1967 (67.148)

Pair of side chairs

The low seat along with the high, lancet-arch-shaped back and tapered stiles give this pair of chairs a strong sense of verticality. Remarkably little Gothic Revival furniture is marked or labeled, making it difficult to identify the makers of these evocative furnishings. In his landmark publication, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), Andrew Jackson Downing praised the accomplished cabinetmakers in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia for their work in this style. The maker of this pair of chairs may have worked in any of these urban centers.

The low seat along with the high, lancet-arch-shaped back and tapered stiles give this pair of chairs a strong sense of verticality. Remarkably little Gothic Revival furniture is marked or labeled, making it difficult to identify the makers of these evocative furnishings. In his landmark publication, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), Andrew Jackson Downing praised the accomplished cabinetmakers in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia for their work in this style. The maker of this pair of chairs may have worked in any of these urban centers.

Image: Side chair, one of a pair. American, 1850–60. Wood, 49 3/4 x 18 3/8 x 21 1/8 in. (126.4 x 46.7 x 53.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1982(1982.208.2)

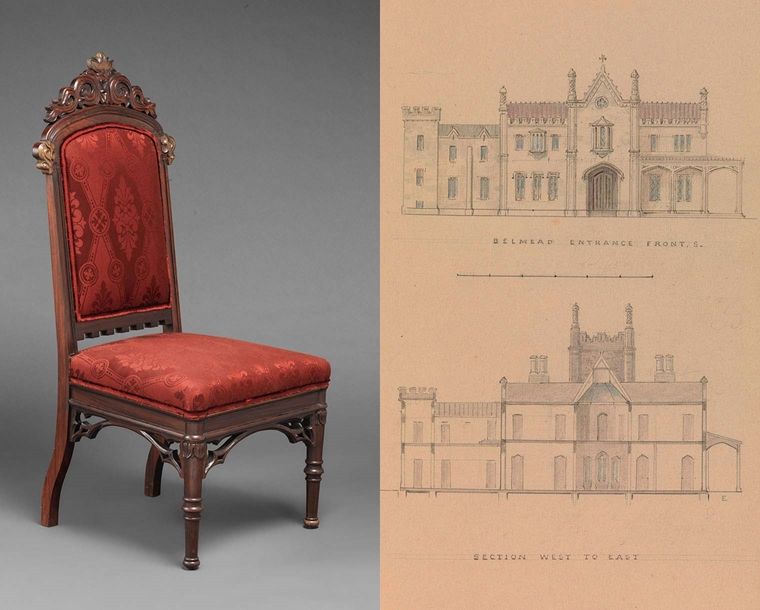

Side chair

Left: Side chair, designed by Alexander Jackson Davis. American, ca. 1848. Rosewood, 42 x 18 1/2 x 21 1/2 in. (106.7 x 47 x 54.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1979 (1979.182); Right: Alexander Jackson Davis (American, 1803–1892). "Belmead," James River, Virginia: Entrance façade and west-east section (recto); North-south section and upper floorplan (verso), 1845. Watercolor and ink, Sheet: 13 3/8 x 10 1/4 in. (34 x 26 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.66.1404(80))

This side chair was designed as part of a suite of furniture for Belmead plantation, the home of Phillip St. George Cocke (1809–1861), in Powhatan County, Virginia. Built in 1845, the house was designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, as were some of its furnishings. Davis was one of the country's most prominent and prolific architects of the nineteenth century and worked closely with Andrew Jackson Downing. Davis worked in a variety of revival styles but is perhaps best known for his domestic architecture in the Gothic Revival style. This chair was manufactured by the New York cabinetmakers William Burns and Peter Trainque, who produced a number of Davis's designs from 1842 until 1856.

Bread plate

Widely recognized as an iconic design of the Gothic Revival, the "Waste Not Want Not," bread plate captures the moralizing intentions behind the work of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, the British architect often viewed as the father of Gothic Revival style. Around the rim, the Gothic script inscription is punctuated by small rosettes. The flat and conventionalized patterning of the central design on the plate recalls the tracery of rose windows found in Gothic cathedrals, and the conventionalized radiating ears of wheat serve as a direct reference to the plate's function.

The English ceramic manufactory Minton executed this design using the encaustic process, a revived medieval ceramic technique by which the design or pattern is created with contrasting colors of clay or slip, as opposed to applied glazes. This example uses four colors—blue, white, tan, and terracotta—but three- and six-color versions of the plate are also known. The encaustic technique was frequently used to create artistic ceramic floor tiles, like those used in Morningside's entrance hall and installed in Gallery 740. These floor tiles were not only durable, but alluded to traditional ceramic crafts.

Image: Bread plate, designed by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. British, ca. 1850. Earthenware, Diam. 13 in. (33 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1986 (1986.241)

Rug

Rug on view in the Gothic Revival Library; Needlepoint rug (detail). American or British, ca. 1860. Wool, embroidered in cross-stitch, 86 x 133 in. (218.4 x 337.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Ernest du Pont Jr., 1980 (1980.500)

This handmade wool needlepoint rug may be either English or American. The repeating pattern of medallions is framed by a foliate border. Though not original to the room, the brown ground and muted color palette complement the room's original woodwork and painted decoration.

Chandelier

This bronze and brass Gothic chandelier once lit the parlor of a Gothic Revival cottage at 86 Spring Street, Portland, Maine, which was designed by architect Henry Rowe. On its four scrolling branches are Gothicized classical anthemia with pendants, which extend from the lower paneled urn with Gothic tracery decoration. The brass baluster is further decorated with applied cast-bronze Gothic ornament. When illuminated, the flickering gas lighting would have created a dramatic play of light and shadow against the gilded fixture and glass shades.

This bronze and brass Gothic chandelier once lit the parlor of a Gothic Revival cottage at 86 Spring Street, Portland, Maine, which was designed by architect Henry Rowe. On its four scrolling branches are Gothicized classical anthemia with pendants, which extend from the lower paneled urn with Gothic tracery decoration. The brass baluster is further decorated with applied cast-bronze Gothic ornament. When illuminated, the flickering gas lighting would have created a dramatic play of light and shadow against the gilded fixture and glass shades.

Image: Chandelier, attributed to Archer and Warner. American, 1845. Brass, bronze, H. 40 in. (101.6 cm); Diam. 31 1/2 in. (80 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1967 (67.193)

Solar lamp

This table-top lamp utilizes a variation of the oil-burning lighting technology advanced by the eighteenth-century Swiss chemist Amie Argand. The small oil reservoir and wick at the top are enclosed in a frosted-glass shade etched with pointed arch windows alternating with baskets of flowers. The gilt-bronze base features Gothic decoration, such as arches and sprockets. The dangling crystals further enhanced the dazzling effects of this fixture.

Image: Cornelius and Son, Solar lamp. American, 1843–49. Gilt bronze, glass, H. 27 in. (68.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Edward J. Scheider Gift, 1986 (1986.20)

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Clasped Hands of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (American, 1830–1908). Clasped Hands of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1853, cast after 1853. Bronze, 3 1/4 x 8 1/4 x 4 1/4 in. (8.3 x 21 x 10.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Frederick A. Stoughton Gift, 1986 (1986.52)

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, an expatriate artist living in Rome, was one of the first American women sculptors to achieve an international reputation. Shortly after meeting the English poets Robert Browning (1812–1889) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861) in 1853, she suggested making a cast of the couple's interlocked right hands. Elizabeth Browning consented, provided Hosmer complete the process herself rather than delegate it to studio assistants. The result is an intimate expression of the love between the Brownings, who had eloped to Italy seven years earlier, and of the warm friendship they shared with Hosmer. The identity of each clasped hand is discernible by the differences in size as well as by the treatment of the cuff at each wrist. Novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne characterized the sculpture, which was cast in both plaster and bronze, as "symbolizing the individuality and heroic union of two high, poetic lives!"

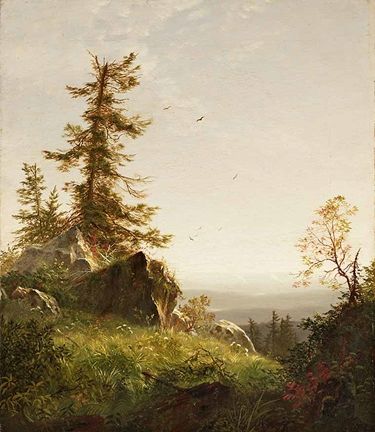

James M. Hart, Mountain Range and Goadesberg

The younger brother of landscape painter William Hart, James Hart began his career as a coach and sign painter in Albany, New York. In 1850, he departed for Europe to advance his artistic training, studying first in Munich and then in Düsseldorf under the tutelage of German landscape painter Friedrich Wilhelm Schirmer. While abroad, Hart completed several on-the-spot landscape sketches, including these two oil studies. The inscription "Goadesberg" on his sketch from May 9, 1852, is probably a reference to the town Bad Godesberg, located on the Rhine River where Hart executed this freely painted vignette of an overgrown rocky landscape. He also painted vibrant views in the Alps, including Mountain Range, a brightly colored sunset scene likely depicting the Tyrol. After three formative years overseas, Hart returned to New York, where he continued to paint landscapes, specializing in bucolic scenes with cattle, oxen, and other farm animals.

Top: James M. Hart (American, 1828–1901).Goadesberg, 1862. Oil on wove paper, 12 1/4 x 9 1/2 in. (31.1 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1973 (1973.14.4); Bottom: James M. Hart (American, 1828–1901). Mountain Range, 1850–55. Oil on wove paper, 9 1/2 x 13 in. (24.1 x 33 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1973 (1973.14.3)

Daniel Huntington, Mary Inman

This portrait of Mary Inman (1827–1860) has been known by several titles, including "The Artist's Daughter," "The White Plume," and "Beatrice." When first acquired by the Museum, it was mistakenly attributed to the sitter's father, the artist Henry Inman, but has since been identified as being by Inman's student and close friend, Daniel Huntington, who likely painted it as a gift for his teacher. With her plumed hat and cloak, Mary may be portrayed in the guise of the witty and free-spirited Beatrice from Shakespeare's As You Like It. The loosely painted landscape in the background evokes the romanticism of Shakespeare's work that resonated with the spirit of the Gothic Revival.

Image: Daniel Huntington (American, 1816–1906). Mary Inman, 1844. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Dave Hennen Coddington, in memory of her husband, 1964 (64.95)

Edwin White, The Antiquary

Edwin White (1817–1877). The Antiquary, 1855. Oil on canvas, 22 1/4 x 27 1/4 in. (56.5 x 69.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Edwin White, 1877 (77.5)

Born in South Hadley, Massachusetts, Edwin White began his career as a portrait painter in Hartford, Connecticut. After his election as academician at the National Academy of Design in 1849, he moved to Paris to continue his studies in portrait, genre, and history painting. Completed while abroad, this work reveals his adoption of the then-fashionable style of romantic genre painting. It features a sixteenth-century Florentine collector carefully examining a coin in an ornately furnished Renaissance interior. Although the artist paid close attention to accurately depicting different textures and materials—including a woven tapestry, a carved wooden chest, a stone mantel, and a metal box—the finished work is more evocative of the Renaissance than it is historically accurate. Nevertheless, White's period works epitomize the Victorian fascination with the past.

John Frederick Kensett, Study of Beeches

This oil study is one of thirty-eight works found in John Frederick Kensett's studio after his death in the summer of 1872. Collectively known as "The Last Summer's Work," these paintings were donated to The Met by the artist's brother, Thomas Kensett, in 1874. The title of this work is evidently a misnomer, as the trees are not beeches but birches with their characteristic white bark and thin leaves. The study's small scale and rapid brushwork indicate that Kensett was likely working en plein air, possibly on the shores of Lake George, where he executed several landscapes throughout his career (see, for example, 15.30.61 and 74.12). On-the-spot sketches such as this informed Kensett's finished studio oils, many of which include detailed renderings of shoreline trees and foliage.

Image: John Frederick Kensett (American, 1816–1872), Study of Beeches, 1872. Oil on canvas, 14 3/4 x 10 3/8 in. (37.5 x 26.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas Kensett, 1874 (74.13)

Richard William Hubbard, Morning on the Mountain

Born in Middleton, Connecticut, Richard William Hubbard graduated from Yale before moving to New York City to study with artist Samuel F.B. Morse. After spending a year in England and France—where he sought inspiration in the works of seventeenth-century landscape painter Claude Lorrain—he settled in Brooklyn and in 1842 began exhibiting landscapes at the National Academy of Design. Like many of his contemporaries, Hubbard traveled widely in New York state and New England during the summer months in search of landscape subjects, painting small-scale studies from nature, such as this. These modest works were praised by critics as "gems of quiet beauty" and reveal his ability to capture the natural effects of light and atmosphere. While the absence of distinctive topographical landmarks makes it difficult to identify this scene, it may depict the landscape surrounding North Conway, New Hampshire, an increasingly popular destination for artists during the early 1850s and one Hubbard was known to have visited.

Image: Richard William Hubbard, (American, 1816–1888). Morning on the Mountain, 1856. Oil on canvas, 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 in. (36.2 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Samuel P. Avery, 1920(20.189.2)

Keep Learning

Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892)

Read more about American architect Alexander Jackson Davis in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Storytime with The Met: The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William Joyce

Met librarian Kamaria reads The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William Joyce and connects it to the Gothic Revival Library.