Verplanck Room

Coldenham, New York, 1767

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate

The furniture, paintings, and ceramics in this prerevolutionary room, on view in Gallery 718, all belonged to Samuel Verplanck (1739–1820), a member of an influential New York City family, and his Dutch-born wife, Judith Crommelin Verplanck (d. 1803). The Verplancks lived in an elegant Georgian-style brick town house located at 3 Wall Street. The residence, demolished in 1822, was more ornate than the relatively simple architectural setting seen here. This room—including the fireplace wall, paneled dado, and cornice—comes from a house built in 1767 in the Hudson River valley by Elizabeth Ellison and Cadwallader Colden, Jr., descendants of another storied New York family. Since no New York City parlors from the era remained intact at the time the Verplanck descendants donated their heirlooms to The Met in the 1930s and 1940s, the Colden House parlor provided a fine example of mid-eighteenth-century American woodwork.

The Verplanck Room in the American Wing

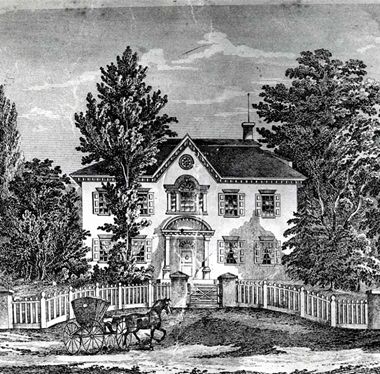

The Colden House

The woodwork in this room comes from the Colden House, built in 1767. It stood within a three-thousand-acre family farm in Coldenham, New York, near Newburgh. No images survive of the house in its original configuration, but the mid-nineteenth-century print shown here supports the physical evidence indicating that the original rough-stone structure was two stories high, five bays wide, and only one room deep.

The house had two parlors on the first floor, one on each side of the central hall. There were two bedchambers above the parlors and a basement kitchen below the east parlor. The paneling was taken from the west parlor and installed in the American Wing in 1940–41.

Image: The Colden House, ca. 1855. This depiction appeared on an 1859 map of Orange and Rockland counties, New York, published by French, Wood, and Bears

Woodwork

By the third quarter of the eighteenth century, the custom of applying full wood paneling to all the walls of a room had given way to the method on view in this room, where only the fireplace wall is paneled. The other three walls have a paneled dado under a chair rail, above which the walls are plastered. A finely carved cornice runs around the room's perimeter at the top.

The Verplanck Room in the American Wing

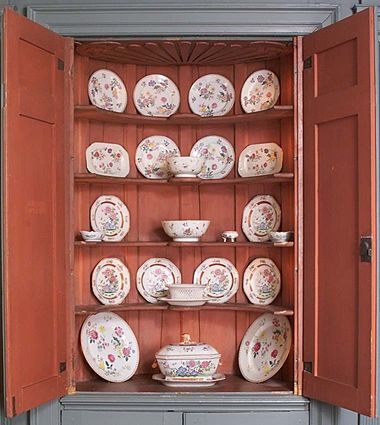

Fireplace, closet, and cupboard

The room's fireplace wall features a simple yet elegant mantelpiece and overmantel, flanked on the right by a narrow closet with hooks at the back for hanging clothing. The china cupboard on the left side of the room has scalloped shelves and is decorated at the top with an unusual carved shell. Instead of appearing in a rounded cove with fanning ribs, facing outward—as would be more typical—the elements of the shells were applied flat against the inside top of the cupboard, where its intricacies are difficult to view.

Image: China cupboard with shell detail visible at the top

No. 3 Wall Street

Left: In View up Wall Street with City Hall (ca. 1789) by Archibald Robertson, a section of the Verplanck's town house at 3 Wall Street appears behind the tree at the right. Collection of The New-York Historical Society. Right: Facade of the Branch Bank of the United States, installed as the entrance to the American Wing in 1924. The bank, designed by Martin E. Thompson, was built between 1822 and 1824.

The furniture in this room was originally used in Samuel and Judith Verplanck's substantial town house in Lower Manhattan. The house and garden fronted the north side of Wall Street. A stable stood in the rear on Pine Street. To the west was City Hall, renamed Federal Hall in 1789, when George Washington was inaugurated there.

Gulian Verplanck, Samuel's father, built the Georgian-style brick town house sometime before 1750. Judith and Samuel Verplanck began living in the house in 1763 when they returned from a brief residence in Amsterdam. After Judith's death in 1803, the furnishings of 3 Wall Street were moved to Fishkill, New York, where Samuel then resided. The Manhattan house was rented until 1822, when the Branch Bank of the United States purchased it, along with the surrounding lots. After demolishing the former Verplanck home, the bank's directors erected a grand building of Tuckahoe marble. The Museum purchased the bank's facade in 1915. It is on display in the Charles Engelhard Court of the American Wing (Gallery 700).

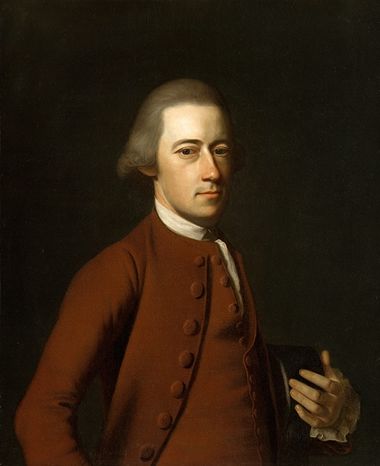

Samuel Verplanck

Samuel Verplanck (1739–1820) was a fifth-generation New Yorker. The first student to enroll in King's College (now Columbia University) when it opened in 1754, Samuel graduated in 1759 and then worked at the Amsterdam banking firm of his maternal uncle, Daniel Crommelin. While there, he married his first cousin (Daniel's daughter), Judith Crommelin in 1761. The couple returned to New York in 1763. A gentleman merchant, Samuel Verplanck was one of the founders of the New York Chamber of Commerce. He also served as a delegate to the New York Provincial Congress and signed the Declaration of Association and Union against Great Britain. A supporter of the revolutionary cause, Samuel relocated to Mount Gulian, his family's homestead in Fishkill, New York in 1775, a year before the British occupied New York City. He continued to reside there until his death in 1820.

Image: John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815), Samuel Verplanck, 1771. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck, 1939 (39.173)

Judith Crommelin Verplanck

Left: Samuel Verplanck presented Judith Crommelin with this diamond ring upon their engagement in 1760. Ring, ca 1760. European, possibly English or Dutch. Gold, diamonds. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Bayard Verplanck, 1955 (55.32). Right: John Singleton Copley painted this portrait of Samuel and Judith Verplanck's son, Daniel Crommelin Verplanck (1762–1834) in 1771. A graduate of King's College in New York, Daniel chose law as his career and served in the United States Congress. John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815). Daniel Crommelin Verplanck, 1771. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Bayard Verplanck, 1949 (49.12)

The Dutch-born Judith Crommelin (d. 1803) married her cousin Samuel Verplanck in Amsterdam in 1761. Characteristic of the period, this marriage helped consolidate the mercantile interests of both families. Judith's dowry included twenty-five thousand florins and a quantity of diamond jewelry and pearls, as well as linens, lace, dress and upholstery fabric, and silverware.

Following the birth of their son, Daniel, the Verplancks returned to New York in 1763 and moved into the town house that Samuel inherited from his father at 3 Wall Street. While Samuel supported the revolutionary cause and retreated to the family's country estate during the war, Judith, a Loyalist, remained in Manhattan and hosted prominent British military and colonial officials, including Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief of the British forces. Judith and Samuel remained estranged until her death in 1803.

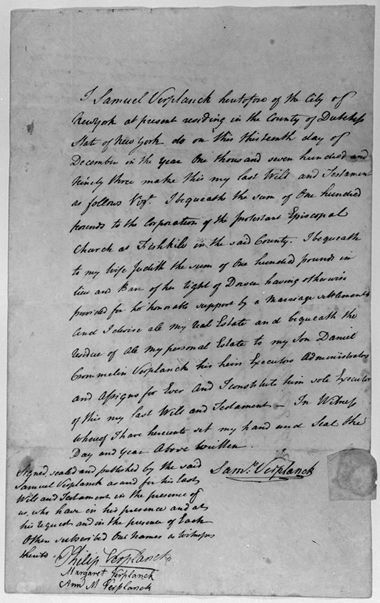

Documenting the Verplancks

Samuel Verplanck graduated from King's College in 1759. The Museum has his diploma. Graduation Diploma, 1759. New York. Sheepskin paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1940 (40.176.2)

The Museum's collection of furniture and furnishings owned by the Verplancks is enhanced by a collection of numerous family documents. This archive helps chronicle the couple's lives and enriches our understanding of the objects they owned. For example, Samuel and Judith's marriage contract describes the luxurious goods included in the bride's dowry.

Thanks to these important records, we know that Samuel Verplanck's will stipulated that his son Daniel was to inherit all of his real estate and personal items while his estranged wife, Judith, was bequeathed the relatively paltry sum of £100.

Image: Samuel Verplanck's will written in Dutchess County, New York on December 12, 1793. Samuel Verplanck (1739–1820). Will, 1793. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. T. Bache Bleecker, 1941 (41.104.1)

Fine textiles

This corded-and-quilted dressing-table cover was made in the first half of the eighteenth century in Marseilles, France. Dressing table cover quilt, 1700–50. Dutch. Cotton, linen binding, and linen fringe. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mary Eastwood and Gertrude Knevels, 1940 (40.136.2)

Judith Crommelin Verplanck was descended from French textile merchants. In 1557, the family built a manufactory for linen and fine cotton in Saint Quentin, France. Later generations of the Crommelin family moved to the Netherlands, where they started a linen-weaving factory at the end of the seventeenth century.

Samuel and Judith Verplanck's wealth allowed them to own textiles of the highest quality. The imported French dressing-table cover pictured here accompanied Judith to America. The white satin waistcoat belonged to Samuel and features delicate embroidery around the neck, front, and bottom. It also has twelve gold-covered buttons and gold-bound buttonholes.

Image: Samuel Verplanck's waistcoat, ca. 1760. British or French. Silk and metal on silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1941 (41.131)

Wedding dress

Left: Judith Verplanck's wedding dress, ca. 1760. British or French. Silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mary Eastwood and Gertrude Knevels, 1940 (40.136.1a, b). Right: Judith Verplanck's wedding dress was worn by a Verplanck family member, seen at center, in Fishkill Landing, New York, ca. 1890.

Judith Crommelin's spectacular wedding dress was made of pale green silk brocade with a multicolored floral design. The sleeves were trimmed in handmade lace.

A new palette

The blue paint (left) was replaced with the original eighteenth-century gray color paint (right).

The Verplanck Room was originally installed at the Museum in 1941. When curators were contemplating a 2008 reinstallation of the room, they took advantage of new scholarship. Scientific analysis of paint fragments taken from the molding revealed two layers of eighteenth-century paint: tan and gray. The curators opted for the gray color as a better complement to the pumpkin-colored upholstery fabric. To replicate the color, texture, and gloss of eighteenth-century paint, a team of conservators mixed hand-ground pigments with linseed oil. Skilled painters then applied the paint with round- and square-shaped boar's-hair brushes. Not all of the paint is new, however. The vermillion interior of the cupboard dates back to the eighteenth century.

The Colden House

The Museum acquired the west parlor of the Colden House in 1940, just before the derelict house was demolished. When the room was installed in the American Wing in 1941, it was lengthened by about four feet in order to accommodate all of the Verplanck furniture. During the 2008 reinstallation, the room was returned to its original size, and one of the room's three windows was made into a doorway so that visitors can pass through the room.

Image: The Colden House in 1940. American Wing curatorial files

Upholstery

The inspiration for the room's upholstery and window hangings is a fabric once owned by the Verplancks. Descendants donated the pumpkin-colored eighteenth-century wool damask to the Museum in 1941. Curators used this original material to upholster the furniture when the room was first installed. After the eighteenth-century fabric wore out in the 1960s, it was replaced with the reproduction fabric that is still in use today.

The room's window valances are also made of reproduction fabric. Their shape and style were copied from valances given by the Verplanck family in 1939.

Image: Verplanck Room window.

A Taste for the Rococo

The Verplanck Room

When the descendants of Samuel and Judith Verplanck donated their furniture and furnishings to The Met, the primary condition of the gift was that the collection be exhibited in one room. This requirement created a unique opportunity to display the full flowering of the New York Rococo, or Chippendale style, with its unique blending of French Rococo, chinoiserie, and Gothic elements. The upholstered settee, card table, and four side chairs were all made by the same cabinetmaker's shop in New York City and were purchased by the Verplancks in the mid-1760s.

A card party

As shown in An Evening Party, card playing at parties allowed women to compete with men on equal terms. Whist and quadrille were often part of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century courtship rituals. George Cruikshank (British, 1792–1878). An Evening Party, February 3, 1826. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Henry G. Friedman Bequest, 1967 (67.539.58)

Card playing was a fashionable, often passionate, pastime in colonial New York. Card games at home took place in the early afternoon or after the evening meal. When Rebecca Franks of Philadelphia visited the city in 1781, she wrote to her sister that "few New York ladies know how to entertain company in their houses unless they introduce card tables."

Not restricted to any particular class or segment of society, cards were played in elegant parlors, assembly houses, and taverns. The parlor game of whist involved both skill and chance. Fast and exciting, the game of loo often resulted in the quick loss of large sums of money. Fargo and vingt-un (known today as blackjack) depended largely on the arbitrary fall of cards.

Image: Card table, ca. 1765. New York. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, birch, and tulip poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.12)

This turret-top card table, so called for its projecting rounded corners to support candlesticks, descended in the Verplanck family along with the four side chairs placed around the table. As is typical of New York-made tables, this example has pronounced gadrooned edging that continues above the legs; cabriole legs with rounded, powerfully curved knees and ankles; and somewhat squashed claw-and-ball feet with small back talons. Green baize, a felt-like woolen fabric, customarily covered the playing surface, and the four oval dishes held gaming counters. The heavy walnut frames, balloon-shaped seats, and absence of Rococo carving suggest that these side chairs were made for Samuel Verplanck shortly after his marriage in 1761.

Image: Side chair (one of six), 1760–90. Probably New York. Walnut, white oak, and white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James DeLancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.3)

Tea parties

Left: Benjamin Brewood II (London, active from 1755). Teakettle. 1762–63. Silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Ernest R. Adee, 1940 (40.160a). Right: Emik Romer (Norwegian, active London). Tea canister, 1762–63. Silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William S. Verplanck, 1959 (59.30)

The consumption of tea was an established ritual in prerevolutionary New York. A hostess would serve it in the afternoon at a table around which guests sat or stood. She would often brew several different kinds of tea and offer sugar, saffron, or peach leaves for extra flavoring. To ensure good tea, the Corporation of New York installed water pumps throughout the city. The most desirable water came from the springs at Chatham and Roosevelt Streets. Peddlers offering this water cried, "Tea water! Tea water!" as they roved up and down the streets of New York.

Judith Verplanck and her husband owned several London-made silver tea wares, including this teakettle-on-stand and tea canister. The repoussé-decorated forms with shells and C-scrolls represent the height of English Rococo styling. The leather tea chest with silver mounts, also made abroad, provided a fashionable, yet secure place for the family to store their imported teas.

Image: Tea chest, 1762–63. England. Leather, wood, and silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Judith C. Verplanck, 1940 (40.104)

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of Samuel Verplanck

Samuel Verplanck (1739–1820) was the original owner of the furniture in the Verplanck Room. This portrait is unsigned and undated but can be assigned to 1771, when John Singleton Copley made his sole trip to New York. The artist also painted Samuel Verplanck's brother Gulian, as well as his son, Daniel Crommelin Verplanck.

Image: John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815). Samuel Verplanck, 1771. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck, 1939 (39.173)

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of Gulian Verplanck

Gulian Verplanck (1751–1799) was the youngest brother of Samuel Verplanck, the original owner of the room's furnishings. Gulian graduated from King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1768 and, like his brother, spent several years in the Netherlands working at the banking firm of his maternal uncle, Daniel Crommelin. In 1788, following his return to New York, Gulian was elected to the state assembly, where he served twice as speaker. He also became president of the Bank of New York and, in 1792, helped found the Tontine Association, a precursor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Image: John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815). Gulian Verplanck, 1771. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Bayard Verplanck, 1949 (49.13)

Settee

The high backs and low arms of eighteenth-century upholstered settees were ideal for supporting two or more sitters. The large and deep sofas that supplanted settees were intended for more informal lounging or reclining. This settee was made together with the card table and four side chairs in this room. All descended in the Verplanck family. In 1965 the settee was reupholstered with a modern reproduction of a pumpkin-colored wool damask also given to the Museum by the Verplanck family.

Image: Settee, ca. 1766. New York. Walnut, white pine, and white oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James DeLancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.2)

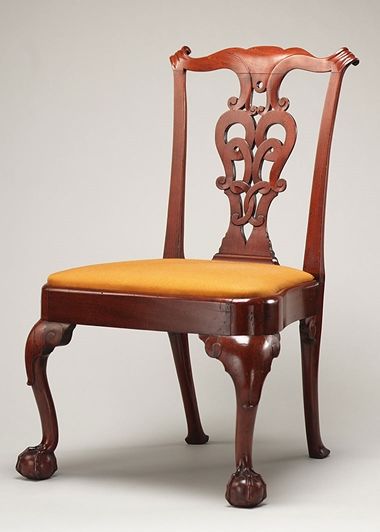

Pair of side chairs

This pair of richly carved Rococo-style side chairs is from a larger set made for Samuel Verplanck in New York around 1765. The carved back splats are Gothic in spirit, a common characteristic of Rococo-style chairs produced in America from English models.

Image: Side chair (one of a pair), 1770–90. New York. Mahogany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Robert Newlin Verplanck, 1940 (40.137.1)

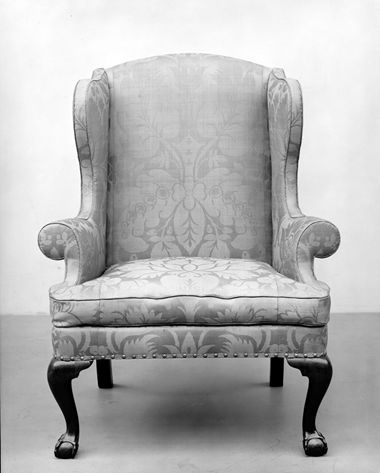

Easy chair

An easy chair was the product of two different craftsmen. The chair maker built the wood armature that determined the chair's basic outline, while the upholsterer determined its ultimate shape. Although the C-scroll arms are typical of Philadelphia work, this chair was produced in New York City. The secondary woods are common in New York–made furniture, as are the square rear legs and the method of joining the seat rails to the front legs. In addition, the claw-and-ball feet—distinguished by a squashed ball with narrow, downward-sloping talons—are distinctively New York.

Image: Easy chair, 1755–90. New York. Walnut, white oak, white pine, and tulip poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.14)

Marble-slab table

Marble-slab table, 1750–70. New York. Mahogany, white oak, sweet gum, white pine, and marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.10)

A New York attribution for this table is supported by its Verplanck family history and the use of local sweet gum as a secondary wood. The bold cavetto-molded skirt with mitered corners is also particular to New York–made furniture. The molded mahogany skirt hides the structural framework of the table.

Desk and bookcase

In 1753 Lieutenant Governor James De Lancey, a grandfather of Mrs. Daniel Verplanck (daughter-in-law to Samuel and Judith), bought this desk and bookcase at an auction. All the items offered for sale had belonged to Sir Danvers Osborne, a colonial governor of New York. Osborne had transported his household furnishings from England to New York City but committed suicide shortly after assuming his post as governor in 1753.

Image: Desk and bookcase, 1700–20. England. Oak and pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James DeLancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.1)

Style of Angelica Kauffman, The Temptation of Eros and The Victory of Eros

Style of Angelica Kauffman. The Temptation of Eros (left) and The Victory of Eros (right), 1750–75. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James DeLancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1939 (39.184.18, .19)

The American Revolution (1775–83) caused a deep rift in the Verplanck household. Samuel Verplanck, a supporter of the rebellion, fled Manhattan in 1775 before the British occupied the city. He never returned. His wife, Judith, sided with the British and chose to stay in their Wall Street house. Her acquaintances included Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief of the British forces. According to family tradition, after Howe was recalled to England, he sent Judith these paintings. Given their depiction of Eros, the Greek god of love and desire (also known as Cupid), in pursuit of a beautiful maiden, they can only be interpreted as love tokens.

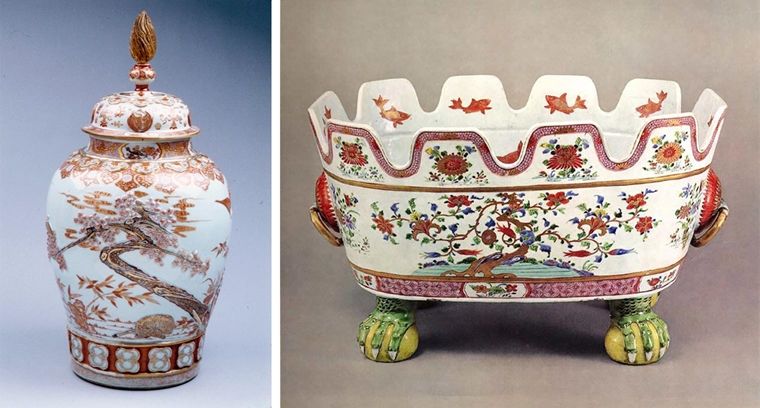

Pair of Hearth Jars and Monteith

Left: Hearth jar (one of a pair), 1750–90. China. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund and Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange, 1971 (1971.140.1a–c). Right: Monteith, early 18th century. China. Porcelain painted in overglaze famille verte enamels and gilt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Harry Payne Bingham, 1974 (1974.369.8)

These Chinese export hearth jars, which belonged to the Verplancks, had a solely decorative function and attested to the status and wealth of the family. Although not owned by the Verplanck family, the large monteith—a large punch bowl—represents a dining form that the family likely owned. Its notched edges supported the stems of drinking vessels, allowing them to be submerged in cold water held in the bowl and offering its user a chilled beverage, a true luxury in an era lacking refrigeration. Such imported porcelains were popular with affluent Americans.

Keep Learning

American Georgian Interiors

(Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

Georgian design, which was characterized by an adherence to theories of order, symmetry, and proportion drawn from classical models during the Renaissance, represented a significant departure from earlier English decorative traditions.

The American Wing

Ever since its establishment in 1870 the Museum has acquired important examples of American Art. A separate "American Wing" building to display the domestic arts of the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries opened in 1924; paintings galleries and an enclosed sculpture court were added in 1980.