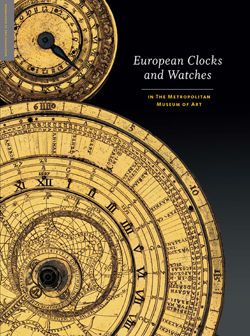

Traveling clock watch with alarm

Watchmaker: Thomas Tompion British

Case and dial maker: Nathanial Delander I British

The origins of the Royal Society can be traced to a loose association of Englishmen interested in science and technology, or what at the time was known as experimental philosophy. By 1645, one group was meeting in the rooms of the warden of Wadham College at Oxford University, while a second group met primarily at Gresham College in London. On November 28, 1660, twelve representatives from both groups (professors of mathematics, physics, and natural philosophy, doctors of medicine, and aristocratic amateurs and patrons of science) met in London to attend a lecture by the Gresham Professor of Astronomy, Christopher Wren (1632–1723). After Wren’s lecture, the group decided to form “a Colledge for the promoting of Physico-Mathematicall Experimentall Learning.” [1] In July 1662 King Charles II (1630–1685) of England granted the group their first royal charter. A second charter from 1663 designated the association “The Royal Society,” the name by which it has been known ever since. Meetings during this early period were chiefly devoted to the performance and discussion of experiments. In 1665, a Curator of Experiments was duly appointed,[2] and Robert Hooke (1635–1703), Gresham Professor of Geometry, became the first member to hold this position.

There is some evidence that Hooke had been trying to develop a balance spring for watches as far back as 1658, but there is no written record of his efforts before 1665.[]3 As late as 1675, he was sketching ideas for balance springs in his diary,[4] and contemplating the employment of a straight spring for the same purpose.[5 ]When and how he met Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) is not certain, although it was probably in connection with an astronomical quadrant that Tompion was making for the Royal Society based on Hooke’s design.[6] Hooke’s diary cites numerous meetings with Tompion in 1674, including their discussions about improvements in cutting and finishing the teeth of watch wheels.[7 ]Together, they produced a watch for King Charles with one of Hooke’s balance springs. When initially presented to the king on May 17, 1675, Hooke reported that the king “Received the watch very kindly, it was locked up in his closet.”[8] But a few months later, the king was no longer enthusiastic, citing the ill effects on the watch of a change in the weather.[9]

As a fellow of the Royal Society, Hooke was in a position to read the society’s communications from its foreign correspondents. Three months prior to the presentation of their watch to the English king, Hooke noted in his diary that he had seen the design for a spiral balance spring from Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) and had transcribed it.[10] This spring was the invention that Tompion soon adopted. As with several French watchmakers, Tompion went further by attempting to do away with the fusee, relying solely on the balance spring to regulate the changing force of the mainspring as it unwound. The Metropolitan Museum’s traveling watch is a surviving example from this brief period of experimentation with the new invention.

Oversized watches with sturdy pendants for hanging them in moving conveyances became popular among the wealthy during the second half of the seventeenth century, and they are therefore often called coach watches. In this splendid example, there are separate going, striking, and alarm trains, each with its own power source. The movement consists of two circular brass plates held apart by five extraordinarily fine tulip pillars. The going train consists of three wheels ending in a verge escapement and balance spring. It is driven by a mainspring housed in a pierced and engraved brass barrel. The striking train is driven by a spring that is housed in a pierced and engraved brass going barrel, and it has a three-wheel train ending in a fly and controlled by a count wheel. The bracket for the count wheel is an elaborate openwork arm of blued steel. The alarm train is driven by a smaller spring in a pierced and engraved brass going barrel, which is installed between the barrels for the going and striking trains. It drives a brass wheel, a steel contrate wheel, and a steel escape wheel. A hammer mounted above the spring barrel of the striking train strikes hours on a bell mounted inside the case, and a crescent-shaped steel arm mounted on the opposite side of the movement strikes the alarm. The watch has a duration of thirty hours.[11]

The back plate has a large cock attached by a screw with a symmetrically pierced and engraved design of floral and foliate scroll ornament that ends in an unusual mattefinished rectangle enclosing a stylized flower. A circular figure plate marked (5–30) for adjusting the balance spring and a smaller silver figure plate (4–20) that indicates the setup of the mainspring of the going train flank the engraved signature: “Tho Tompion London.” On the left side, above the figure plate for the balance spring adjustment, is a figure plate for the setup of the striking train, and above the figure plate is a silver count wheel (1- I I ) for the striking train.

The dial consists of a champlevé silver chapter of hours (I–XII), marked for quarters (lines) and half hours (dots). In the center, there is a circular revolving dial for the alarm with a chapter of Arabic numerals (1–11) for the hours and a single, openwork hand attached at the twelve o’clock position.

A second single hand attached at the center sets the alarm. The two chapter rings are separated by a band of floral scrolls, and the motif is repeated in the center of the alarm dial. The case has a glass cover for the dial with a hinged silver bezel. The circular design in the center of the back of the case displays a subtle interplay between the engraved and chased floral scrolls incorporating lilies and anemones and the recessed ground of chiseled silver. The design is framed by a wreath made up of tripartite leaf forms that are punctuated by six rosettes, which are, in turn, encircled by an openwork ring of engraved floral scrolls composed of lilies, daffodils, and anemones. These same motifs appear, as well, on the dial, and the circle of leaves and rosettes repeats on the bezel for the glass cover of the dial. The initials “ND” conjoined (the casemaker’s mark for Nathaniel Delander until at least 1682)[12] are punched on the interior of the case under the bell. The crab (a mark for small silver articles of .800 standard fineness used by provincial French assay offices beginning in 1838) appears twice on the pendant.[13]

There would have been a protective outer case for this watch, but it is missing. The pendant has been slightly bent. The figure plate for the setup of the spring of the alarm train is missing, and the figure plates for the setup of the springs of the going and striking trains have been repaired. The contrate wheel in the going train is a replacement. Otherwise, the watch is reasonably close to its original condition.

The presence of the French guarantee marks for silver indicates that the watch had at least one owner in France during the nineteenth century before it entered the collection of the British banker Frederick George Hilton Price in 1898. The watch became one of the glories of J. Pierpont Morgan’s collection when he acquired it from Hilton Price.[14]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Harrison 1911, pp. 791–92.

[2] Ibid., p. 792. See also Inwood 2002, pp. 30–33, for an extended account of Hooke’s appointments in this period.

[3] Hall 1978, pp. 262–63.

[4] See Hooke 1968, p. 151, entry of Mar. 8, 1674/75, and p. 164, entry of June 13, 1675.

[5] Ibid., p. 177, entry of Aug. 30, 1675.

[6] J. L. Evans 2006, p. 22, and p. 19, fig. 18.

[7 ]Hooke 1968, p. 100, entry of May 2, 1674.

[8] Ibid., p. 161, entry of May 17, 1675.

[9 ]Ibid., p. 185, entry of Oct. 5, 1675.

[10 ]Ibid., p. 153, entry of Mar. 18, 1674/75. For further details of the Hooke-Tompion project and the subsequent dispute between Hooke and Huygens about the priority of the invention, see Hall 1951; Hall 1978, pp. 269–71; Inwood 2002, pp. 203–15. See also entry for 17.190.1417 in this volume.

[11] For a more detailed description of the movement, see J. L. Evans, Carter, and Wright 2013, pp. 266, 565.

[12] Priestley 2000, pp. 19, 66.

[13] See Tardy 1981c, pp. 199–200.

[14] Williamson 1912, p. 147, no. 159, and pl. lxxi.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.