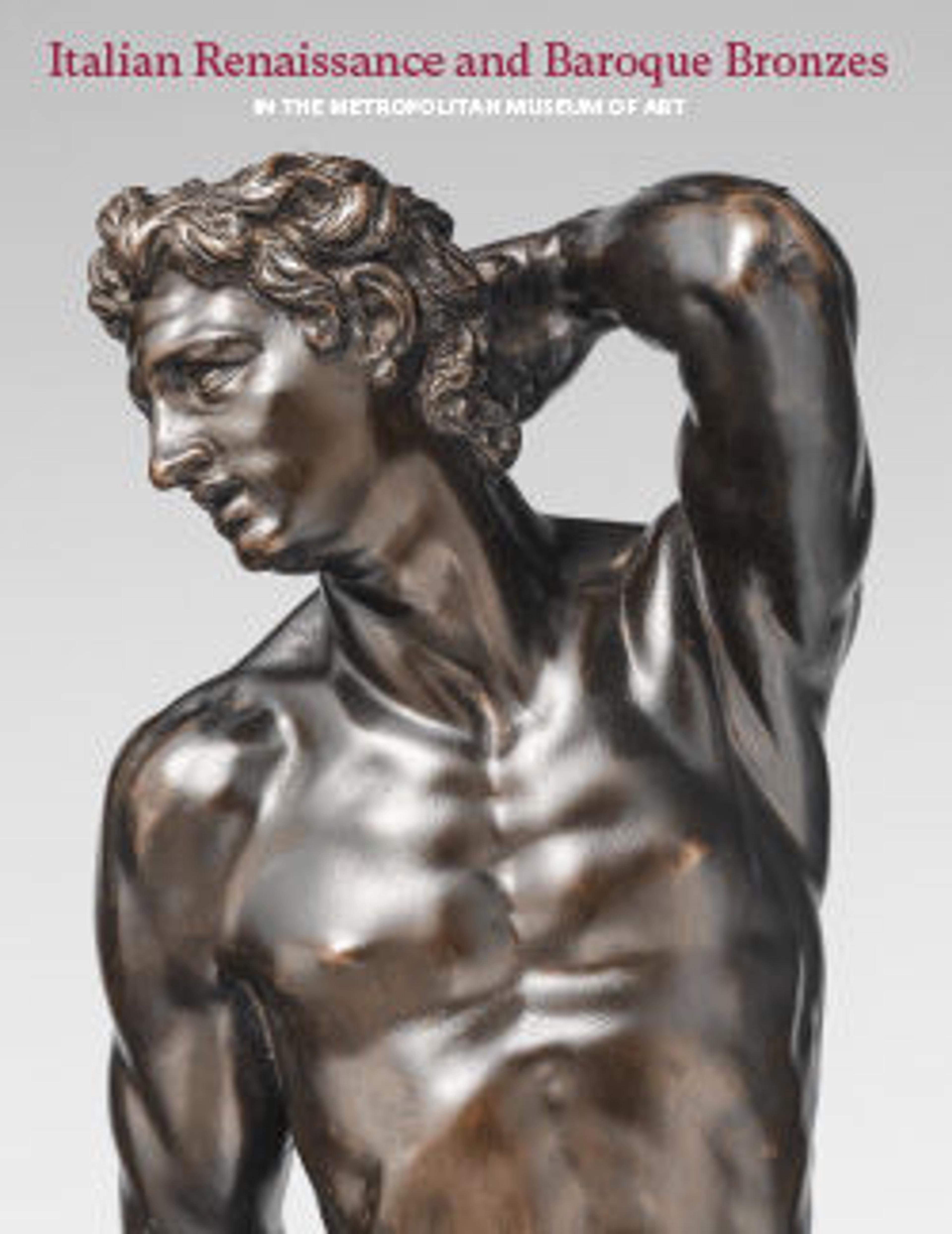

The Virgin Mary

Despite exhibiting different styles and factures, the likenesses of Saint John, one of which is paired with an image of the Virgin Mary, warrant discussion together, for they offer a rare opportunity to examine early Renaissance casts of the same composition. All three bronzes, acquired a few years apart, reflect the Late Gothic compositional habits of the fifteenth-century Sienese school of sculpture that began with Jacopo della Quercia and continued through Vecchietta and Neroccio di Bartolommeo de’ Landi. The hallmarks of the school are firm, oblong silhouettes often enclosing quite agitated draperies and fervent facial expressions.

All were acquired as Sienese. The Virgin–Saint John pair was for a time thought to be from the workshop of Neroccio, and the single Saint John merely Sienese. The painter Neroccio, only rarely encountered with certainty as a sculptor, still provides the best stylistic comparisons overall.[1] Outstanding productions are his polychrome wood Saint Catherine of Siena (1474), in the oratory of that saint, Siena, and a marble Saint Catherine of Alexandria in Siena Cathedral, apparently still unfinished at his death,[2] but the posthumous inventory of his estate registers the tools, materials, and models employed by sculptors. The important aspect of the two Neroccio sculptures in relation to our bronzes is their nervous falls of drapery within mellow contours, still in the tradition of the Late Gothic and della Quercia. But Neroccio remains a mere point of departure.

The Virgin and Saint John pair, by long-standing usage, undoubtedly flanked a crucifix, itself very likely of bronze, the Virgin to the right of Christ, John to his left. John, “the beloved disciple,” regularly rests his right cheek in his right hand in sorrowful contemplation.[3] A cross by the Sienese silversmith Goro di Ser Neroccio (unrelated to the painter-sculptor) in the Museo Diocesano, Pienza, signed and dated 1430, offers a suggestive arrangement.[4] Curved stems below the cross support the Virgin to its right; a missing John was no doubt to Christ’s left.

Bronze chief mourners flanking corpora existed in many locales; the best known may be two, dismounted in the Ashmolean, convincingly attributed to Filarete.[5] In this case, it is the Virgin who rests her cheek on one hand. Closer to home, a 1482 inventory of Siena Cathedral’s treasury lists “a cross in bronze [attone, i.e., ottone, or brass/bronze], with a Crucifix in relief, with two figures to the sides, gilt and enameled.”[6]

The paired and the single Saint John are of entirely different facture, the former more massively modeled and cast; it even exhibits differences from the Virgin with which it is paired. This Saint John has a more regular hexagonal base, and the fall of drapery in the back has been milled to imitate the weave of cloth. The Virgin’s base is smaller, its corners less defined. The rich fire gilding of the Saint Johns does not occur on faces and hands so as to offset these more expressive areas within the general glow of gold. Neither seems ever to have had a halo.

The single Saint John is slenderer in form and more linear in treatment. He is also more thinly cast and stands on a plain disk for a self-base. The outstanding difference between him and the pair is that all his hems and fringes are distinguished by punch marks and incised lines, emphasized further by touches of oil gilding (except on the top of his mantle in back), considerably worn. His hair and nails are more carefully indicated than those of his counterpart. The top of his head was flattened and has a hole for a halo.

None of these bronzes is of the highest quality,[7] but it is more than likely that all look back to distinguished prototypes. The endearing plasticity of the pair results from an appreciation of the original models’ relatively broad effects and aspirations toward monumentality. The slenderer build and precious adumbration of detail in the singleton, on the other hand, suggest a silversmith’s wish to satisfy a viewer’s scrutiny at close range.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. My conclusions are indebted to Gertrude M. Helms, “Three Sienese Renaissance Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” master’s thesis, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1979. She does not decide on an author for any of the three, but her work repays close study for its deft analysis of Sienese sculpture, wealth of comparisons, typological citations, and technical discussions.

2. Coor 1961, pp. 177–78, 182, nos. 41, 46, figs. 23–25, 48–50.

3. Vavalà 1929.

4. Elisabetta Cioni in Seidel 2010, pp. 470–71.

5. Spencer 1958.

6. Borghesi and Banchi 1898, p. 265, doc. 164.

7. The three statuettes are bronze alloys with low levels of lead and trace impurities, including silver. R. Stone/TR, November 3, 2008.

8. Their inventory number 37553 appears in white paint on the back of the brown-and-black variegated black marble pedestal, and in ink on the bottom of the pedestal.

All were acquired as Sienese. The Virgin–Saint John pair was for a time thought to be from the workshop of Neroccio, and the single Saint John merely Sienese. The painter Neroccio, only rarely encountered with certainty as a sculptor, still provides the best stylistic comparisons overall.[1] Outstanding productions are his polychrome wood Saint Catherine of Siena (1474), in the oratory of that saint, Siena, and a marble Saint Catherine of Alexandria in Siena Cathedral, apparently still unfinished at his death,[2] but the posthumous inventory of his estate registers the tools, materials, and models employed by sculptors. The important aspect of the two Neroccio sculptures in relation to our bronzes is their nervous falls of drapery within mellow contours, still in the tradition of the Late Gothic and della Quercia. But Neroccio remains a mere point of departure.

The Virgin and Saint John pair, by long-standing usage, undoubtedly flanked a crucifix, itself very likely of bronze, the Virgin to the right of Christ, John to his left. John, “the beloved disciple,” regularly rests his right cheek in his right hand in sorrowful contemplation.[3] A cross by the Sienese silversmith Goro di Ser Neroccio (unrelated to the painter-sculptor) in the Museo Diocesano, Pienza, signed and dated 1430, offers a suggestive arrangement.[4] Curved stems below the cross support the Virgin to its right; a missing John was no doubt to Christ’s left.

Bronze chief mourners flanking corpora existed in many locales; the best known may be two, dismounted in the Ashmolean, convincingly attributed to Filarete.[5] In this case, it is the Virgin who rests her cheek on one hand. Closer to home, a 1482 inventory of Siena Cathedral’s treasury lists “a cross in bronze [attone, i.e., ottone, or brass/bronze], with a Crucifix in relief, with two figures to the sides, gilt and enameled.”[6]

The paired and the single Saint John are of entirely different facture, the former more massively modeled and cast; it even exhibits differences from the Virgin with which it is paired. This Saint John has a more regular hexagonal base, and the fall of drapery in the back has been milled to imitate the weave of cloth. The Virgin’s base is smaller, its corners less defined. The rich fire gilding of the Saint Johns does not occur on faces and hands so as to offset these more expressive areas within the general glow of gold. Neither seems ever to have had a halo.

The single Saint John is slenderer in form and more linear in treatment. He is also more thinly cast and stands on a plain disk for a self-base. The outstanding difference between him and the pair is that all his hems and fringes are distinguished by punch marks and incised lines, emphasized further by touches of oil gilding (except on the top of his mantle in back), considerably worn. His hair and nails are more carefully indicated than those of his counterpart. The top of his head was flattened and has a hole for a halo.

None of these bronzes is of the highest quality,[7] but it is more than likely that all look back to distinguished prototypes. The endearing plasticity of the pair results from an appreciation of the original models’ relatively broad effects and aspirations toward monumentality. The slenderer build and precious adumbration of detail in the singleton, on the other hand, suggest a silversmith’s wish to satisfy a viewer’s scrutiny at close range.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. My conclusions are indebted to Gertrude M. Helms, “Three Sienese Renaissance Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” master’s thesis, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1979. She does not decide on an author for any of the three, but her work repays close study for its deft analysis of Sienese sculpture, wealth of comparisons, typological citations, and technical discussions.

2. Coor 1961, pp. 177–78, 182, nos. 41, 46, figs. 23–25, 48–50.

3. Vavalà 1929.

4. Elisabetta Cioni in Seidel 2010, pp. 470–71.

5. Spencer 1958.

6. Borghesi and Banchi 1898, p. 265, doc. 164.

7. The three statuettes are bronze alloys with low levels of lead and trace impurities, including silver. R. Stone/TR, November 3, 2008.

8. Their inventory number 37553 appears in white paint on the back of the brown-and-black variegated black marble pedestal, and in ink on the bottom of the pedestal.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Virgin Mary

- Artist: Possibly Workshop of Neroccio de' Landi (Italian, Siena 1447–1500 Siena)

- Date: late 15th century

- Culture: Italian, Siena

- Medium: Bronze, partially fire-gilt

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 7 5/8 × 2 1/2 × 1 9/16 in. (19.4 × 6.4 × 4 cm);

Height (base): 3 3/16 in. (8.1 cm) - Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1960

- Object Number: 60.37.1

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.