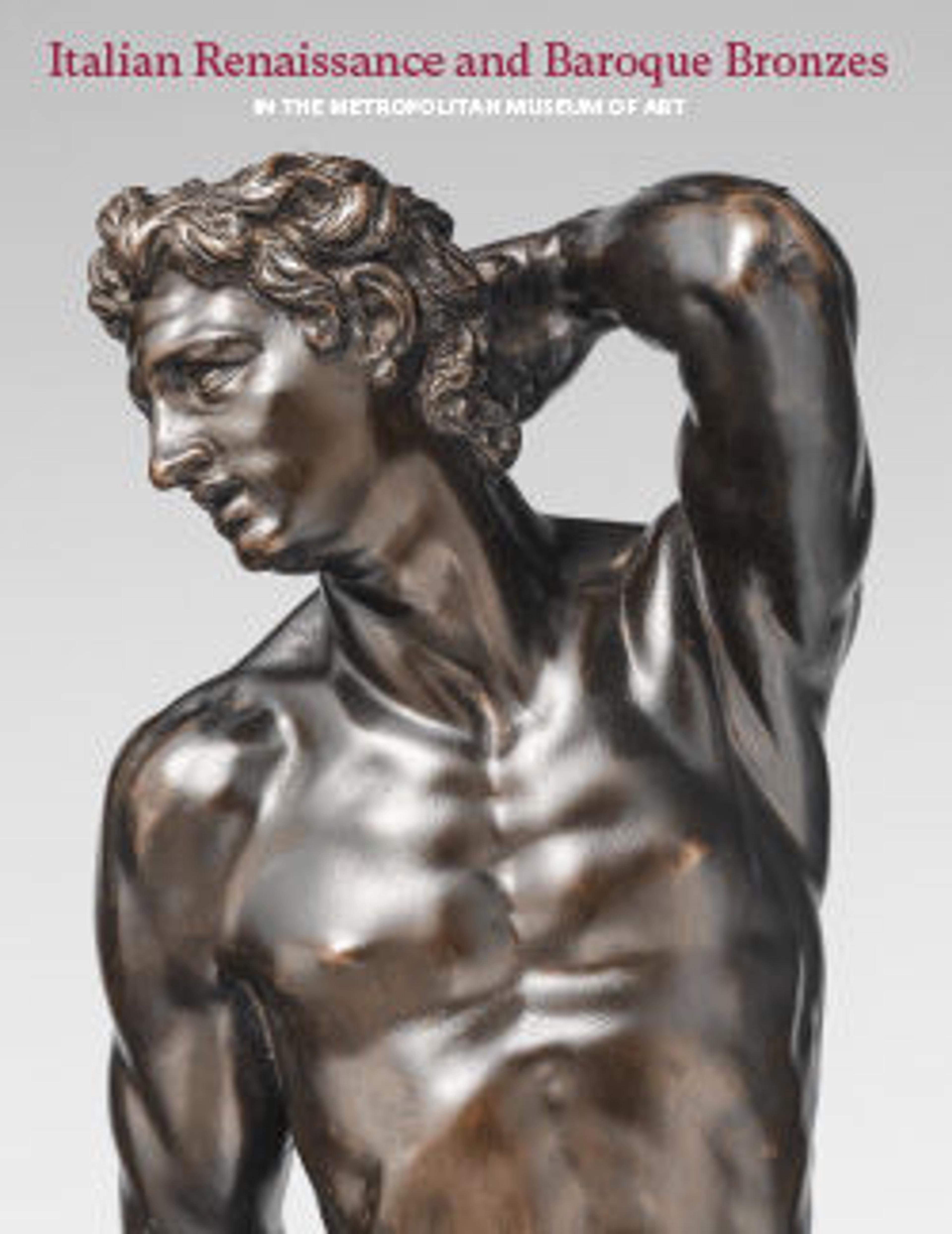

Altar candlestick with busts in relief of Saints Peter and Paul (one of a pair)

All that remains of a once resplendent altar garniture are three pairs of candlesticks with reliefs on their triangular bases displaying attributes of saints: the present pair, Saint Peter with keys and Saint Paul with a sword; a second pair with the angel of Saint Matthew and the ox of Saint Luke, in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York; and a third pair with the lion of Saint Mark and the eagle of Saint John, in the V&A.[1] A crucifix with an equally decorative base would have occupied the center of the altar, flanked by the candelabra with the Four Evangelists.

The Roman Rite stipulates that candles be lit on or behind the altar during the celebration of Mass, flanking a crucifix. The humble beeswax of the candles symbolizes Christ’s body, the wick his soul, and the flame his divinity. Up to six can be lit, always at Sunday Mass, and a seventh can be used by a bishop celebrating in his own diocese.[2] In the course of the Renaissance, candleholders grew in richness, their stems, knobs for handling, drip pans, and prickets offering a host of design options. (The prickets in all six candles discussed here are modern additions.) Our pair would have stood at the ends of the altar if aligned horizontally with the others, unless the altar was stepped, in which case they would have been placed somewhat lower than the rest.

The candlesticks are alike in their stately cadences and in their punched grounds and selective gilding, but their ornamentation has decided variations in all three cases, starting with their triangular bases. Those of our bronzes comprise acanthus resting on animals’ paws; the Morgan candlesticks rise from sphinxes resting on smaller animals’ paws; and the V&A’s rest on horned dolphins. Otherwise they share classical motifs differently massed along their lengths: vertical arrangements of balusters in the shape of bundled acanthus leaves, knobby garlands, and gadroons. Both sets of New York candlesticks add masks and florets. It is uncommon to change the designs of candlesticks within a set, but the six must have achieved a fine visual balance in the distribution of their shapes and details and in the application of their gilding. Having come on the market at roughly the same time, exhibiting identical features of casting (as in the flaws atop the triangular elements, barely retouched by chiseling), and illustrating as they do the Evangelists and the two Church Fathers, there can be little doubt that the group formed a coherent sextet.

It has not proven possible to trace their origins or establish their authorship. An assumption that they are Venetian rests on similarities between their rather blunt High Renaissance ornamental and figural styles and those of the friezes on the flagpole stands in Piazza San Marco by Alessandro Leopardi, with their vivid enactments of sea thiasoi. Curiously, smaller decorative sculptures by Leopardi or his workshop have not been solidly identified,[3] and there is a general feeling among scholars that the candlesticks date to after Leopardi’s death in 1522/23. The attribution to Vincenzo Grandi or his nephew Gian Gerolamo Grandi, active in Padua and especially well seen in Trent, proposed by Wolfram Koeppe and Michelangelo Lupo has not stood the test of time. Koeppe and Lupo have the merit, however, of identifying the style of the set with that of yet another pair of candlesticks, in Trent’s Cathedral of San Vigilio, still in use in its Chapel of the Crucifix. Their sphinx-and-acanthus bases are virtually identical to those in the Morgan pair.[4] Architectural images of the cathedral occur in the spaces occupied by saints on the six under discussion. The Grandi practiced in an altogether more original manner, with ornamentation that is far more svelte and crisply shaped than that of the candlesticks. Massimo Negri was wise to classify them simply as Venetian.

Koeppe and Lupo traced the classical inspiration of the candlesticks to the four Roman marble ones known throughout the Renaissance, restored in the time of Raphael, and now in the Galleria dei Candelabri of the Vatican Museums.[5] The slenderer of the two ancient marble pairs particularly influenced the sphinxes on the feet of the Morgan bronzes and the elegant alternation of balusters and horizontal accents of all six bronze candlesticks under discussion. The ancient designs could have been disseminated all over Italy through eagerly consulted drawings. Saint Matthew’s angel at the Morgan may strike a specifically Paduan note, being highly reminiscent of Donatello’s on the altar of Saint Anthony in the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, Padua.[6] Nothing has emerged, alas, to support Wilhelm von Bode’s claim that they came “from a church in Milan” via “Count Mocenigo.”[7]

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Morgan, AZ035.1–.2; V&A, M.700-1910.

2. “The Different Forms of Celebrating Mass: Mass with a Congregation,” ch. IV.I of General Instruction of the Roman Missal (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2005).

3. See Jestaz 1982 for some well-considered attempts, as well as his photographic coverage of the flagpole’s friezes. Leopardi is best known as the founder of Verrocchio’s equestrian monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni in the Campo di Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice.

4. Dal Prà 1993, p. 375; Negri 2014, p. 151.

5. See Vatican 1984, pp. 97–99, cats. 59–60.

6. Janson 1957, vol. 1, pl. 264.

7. Bode 1910, vol. 2, nos. 110, 111. He did not explain how he obtained the information. The V&A Metalwork Department’s files say that it was supplied by Durlacher Brothers, presumably Salting’s dealer. Luigi Mocenigo was doge as Alvise I Mocenigo from 1570 to 1577. All the candelabra apparently predate his death.

The Roman Rite stipulates that candles be lit on or behind the altar during the celebration of Mass, flanking a crucifix. The humble beeswax of the candles symbolizes Christ’s body, the wick his soul, and the flame his divinity. Up to six can be lit, always at Sunday Mass, and a seventh can be used by a bishop celebrating in his own diocese.[2] In the course of the Renaissance, candleholders grew in richness, their stems, knobs for handling, drip pans, and prickets offering a host of design options. (The prickets in all six candles discussed here are modern additions.) Our pair would have stood at the ends of the altar if aligned horizontally with the others, unless the altar was stepped, in which case they would have been placed somewhat lower than the rest.

The candlesticks are alike in their stately cadences and in their punched grounds and selective gilding, but their ornamentation has decided variations in all three cases, starting with their triangular bases. Those of our bronzes comprise acanthus resting on animals’ paws; the Morgan candlesticks rise from sphinxes resting on smaller animals’ paws; and the V&A’s rest on horned dolphins. Otherwise they share classical motifs differently massed along their lengths: vertical arrangements of balusters in the shape of bundled acanthus leaves, knobby garlands, and gadroons. Both sets of New York candlesticks add masks and florets. It is uncommon to change the designs of candlesticks within a set, but the six must have achieved a fine visual balance in the distribution of their shapes and details and in the application of their gilding. Having come on the market at roughly the same time, exhibiting identical features of casting (as in the flaws atop the triangular elements, barely retouched by chiseling), and illustrating as they do the Evangelists and the two Church Fathers, there can be little doubt that the group formed a coherent sextet.

It has not proven possible to trace their origins or establish their authorship. An assumption that they are Venetian rests on similarities between their rather blunt High Renaissance ornamental and figural styles and those of the friezes on the flagpole stands in Piazza San Marco by Alessandro Leopardi, with their vivid enactments of sea thiasoi. Curiously, smaller decorative sculptures by Leopardi or his workshop have not been solidly identified,[3] and there is a general feeling among scholars that the candlesticks date to after Leopardi’s death in 1522/23. The attribution to Vincenzo Grandi or his nephew Gian Gerolamo Grandi, active in Padua and especially well seen in Trent, proposed by Wolfram Koeppe and Michelangelo Lupo has not stood the test of time. Koeppe and Lupo have the merit, however, of identifying the style of the set with that of yet another pair of candlesticks, in Trent’s Cathedral of San Vigilio, still in use in its Chapel of the Crucifix. Their sphinx-and-acanthus bases are virtually identical to those in the Morgan pair.[4] Architectural images of the cathedral occur in the spaces occupied by saints on the six under discussion. The Grandi practiced in an altogether more original manner, with ornamentation that is far more svelte and crisply shaped than that of the candlesticks. Massimo Negri was wise to classify them simply as Venetian.

Koeppe and Lupo traced the classical inspiration of the candlesticks to the four Roman marble ones known throughout the Renaissance, restored in the time of Raphael, and now in the Galleria dei Candelabri of the Vatican Museums.[5] The slenderer of the two ancient marble pairs particularly influenced the sphinxes on the feet of the Morgan bronzes and the elegant alternation of balusters and horizontal accents of all six bronze candlesticks under discussion. The ancient designs could have been disseminated all over Italy through eagerly consulted drawings. Saint Matthew’s angel at the Morgan may strike a specifically Paduan note, being highly reminiscent of Donatello’s on the altar of Saint Anthony in the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, Padua.[6] Nothing has emerged, alas, to support Wilhelm von Bode’s claim that they came “from a church in Milan” via “Count Mocenigo.”[7]

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Morgan, AZ035.1–.2; V&A, M.700-1910.

2. “The Different Forms of Celebrating Mass: Mass with a Congregation,” ch. IV.I of General Instruction of the Roman Missal (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2005).

3. See Jestaz 1982 for some well-considered attempts, as well as his photographic coverage of the flagpole’s friezes. Leopardi is best known as the founder of Verrocchio’s equestrian monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni in the Campo di Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice.

4. Dal Prà 1993, p. 375; Negri 2014, p. 151.

5. See Vatican 1984, pp. 97–99, cats. 59–60.

6. Janson 1957, vol. 1, pl. 264.

7. Bode 1910, vol. 2, nos. 110, 111. He did not explain how he obtained the information. The V&A Metalwork Department’s files say that it was supplied by Durlacher Brothers, presumably Salting’s dealer. Luigi Mocenigo was doge as Alvise I Mocenigo from 1570 to 1577. All the candelabra apparently predate his death.

Artwork Details

- Title: Altar candlestick with busts in relief of Saints Peter and Paul (one of a pair)

- Artist: Workshop of Vincenzo Grandi (mentioned 1507–1577/78)

- Artist: and Gian Gerolamo Grandi (1508–1560)

- Date: mid-16th century

- Culture: Northern Italian

- Medium: Bronze, partially oil-gilt

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 36 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 13 in. (92.7 × 31.8 × 33 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Ann and George Blumenthal Fund, 1973

- Object Number: 1973.287.1

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.