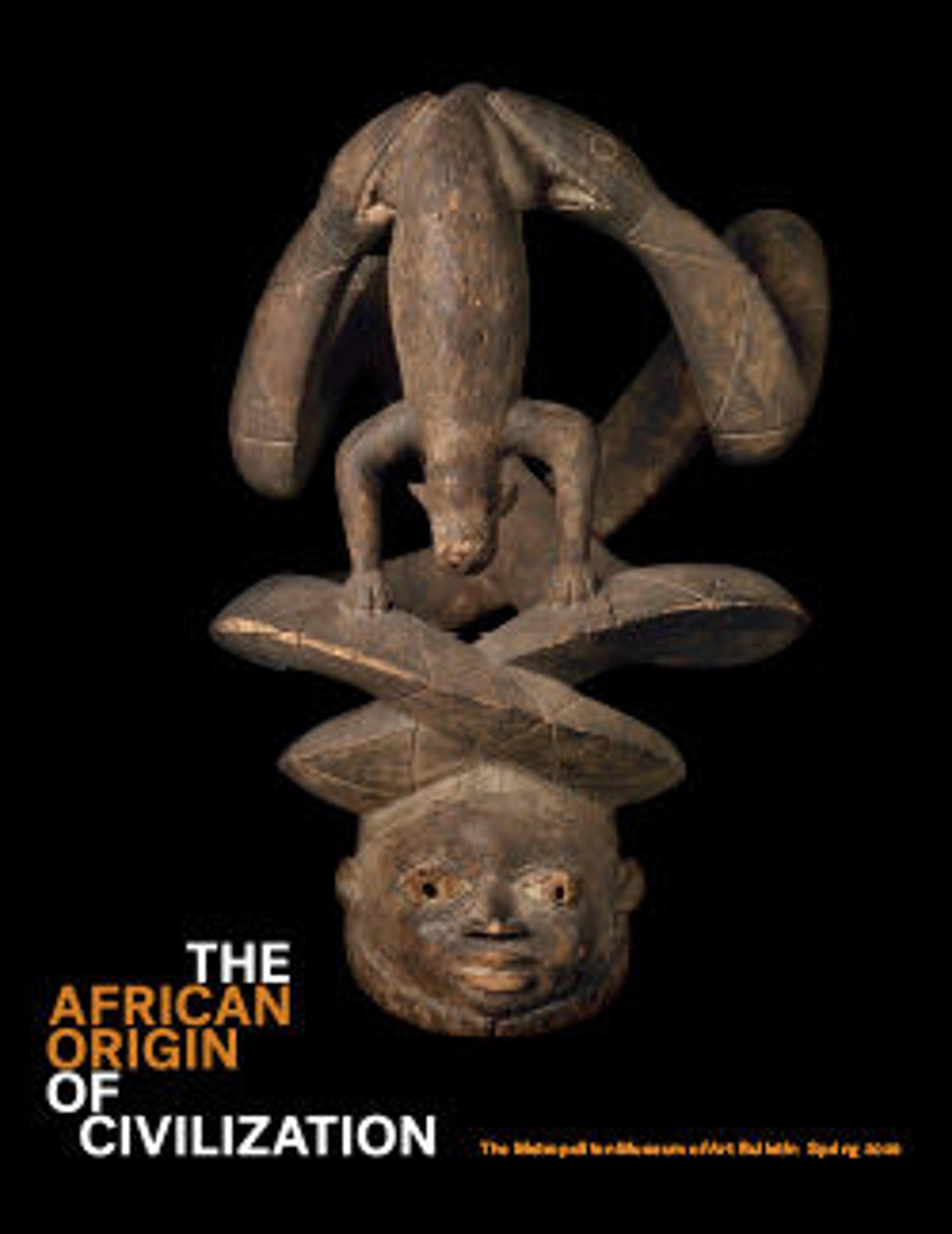

Ȯkyeame poma (royal spokesperson's staff) with stool, chain, and crossed swords

Executed as a direct carving, the finial has boldly delineated imagery of a ceremonial stool, chain, and swords. Done without the aid of preparatory models or drawings, direct carving is commonly used in Africa. The technique was later adopted by European and American modernists like Constantin Brancusi and Chaim Gross in the early twentieth century. Three gathered cylinders form the lowest part of the finial, which in turn supports three columns with large, half-dome bases incised with radiating triangular designs. Thick double-bands encircle the freely carved columns both above their bases and at their summits. A chain of oval-shaped links winds around the group of pillars.

The stool is supported by a two-stepped rectangular base (bambasa), which is just slightly shorter than its rectangular seat. Each of the seat's tapered ends curves gently upwards. Following the conventions of Akan stools, four outside supports flank its supportive central column. The solid central column is unornamented, while the outer supports curve and thicken to form an oval-shaped ring at each of the stool’s sides. The outer supports are further ornamented with delicately peaked scallops along their perimeters. Three Akan state swords (afena) lie with their blades crossed atop the seat of the stool. Wider at their curved tip, the thick blades recede into dumbbell-shaped pommels incised with parallel lines.

Incorporating highly symbolic motifs drawn from the vast visual repertoire of the Akan peoples of Ghana, this golden staff (ȯkyeame poma) is unique for its association with both British colonialism and Ghanaian independence.

The Importance of gold in Akan society

Historically, only royals and members of their entourage could possess precious metals like locally mined gold (sika) and imported silver. Akan gold production likely began in the second half of the fifteenth century, yielding approximately fourteen million ounces of metal by 1900. Gold circulated in powdered form (sika futuro) as the currency of the Asante Empire until 1901. When not accumulated as a form of personal wealth, it was melted down and cast into ornaments. Members of the royal goldsmiths' guild exclusively produced royal gold ornaments, including staffs. They claimed ancestry from Fusu Kwabi, who supposedly descended from heaven in the 1400s to teach men how to work gold. Gold was not only a means of wealth and a way of displaying status, but also a spiritual substance. The shining metal was believed to be the earthly embodiment of the sun, and thus the force of life itself (kra). Regalia—including woven textiles and elaborate gold ornaments—were omnipresent aspects of Akan courtly life since at least the fifteenth century.

Akan courts and royal regalia

The Akan states rose in importance in part as a response to the global demand for gold. Before the rise of the Asante Empire around 1700, smaller Akan states like Adanse, Akwamu, and Denkyira dominated during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. To this day, a paramount chief or king (ȯmanhene) rules each state and retains command over a larger group of regional subchiefs. Regalia belonged to the state, and was thus considered “stool property” (agypadie). Chiefs retained a wide variety of regalia, generally used for personal adornment, which was stored in special warehouses within the royal compound. The Asantehene, leader of the Asante Empire, has the largest quantity of regalia at his disposal: cloths, staffs, stools, swords, ornaments, crowns, sandals, and flywhisks. Due to its size and influence, the court and regalia practices of Asante came to dominate the Akan region. Later, Asante regalia was incorporated into the state iconography of newly-independent Ghana. In any Akan state, the ȯmanhene had a retinue of officials, many of whom used their own regalia drawn from the agypadie. The right of subchiefs and officials to own and display regalia was carefully controlled, and could be revoked or rewarded. Staffs are among the most distinct forms of regalia used by members of the Akan court.

Ȯkyeame: a royal counselor

Ȯkyeame poma are staffs of office used by an ȯkyeame (pl., aykeame), the highest ranking member of the royal or chiefly entourage in the Akan court system. Ȯkyeame are gifted in public speaking, and fully steeped in local lore and the thousands of proverbs that characterize both formal and informal Akan speech. Given their verbal talents, the ȯkyeame’s primary role is to mediate the chief’s speech. The ȯmanhene does not speak directly in formal settings, but rather through the ȯkyeame. This official uses his verbal prowess to simultaneously interpret, embellish, and transmit the message of both parties in a conversation. The ȯkyeame's ability to verbally embroider the ruler’s speech reflects directly upon his employer. Given the closeness of their relationship, they are tied together by both politics and a ceremony of ritual wedlock. In addition to this oratorical role, akyeame also serve as diplomats, prayer officiants, prosecutors, intermediaries, and counsellors. Commonly mistranslated as ‘linguist,’ the term ȯkyeame has no exact translation in English; the term counselor has most recently been accepted as the closest approximation. Once used exclusively in the royal court, aykeame became mediators between clan groups (abusua), and were incorporated into the Ghanaian state by Kwame Nkrumah in 1962, who modified their functions to allow them to take on the role of state speaker. In addition to aykeame, priests and deities may also hold regalia typically identified as “royal,” including aykeame poma. These distinctive staffs of office remain in use today.

Sources disagree on the date of origin for the institution of the ȯkyeame. Some trace it to the reign of Ewurade Basa (ca. 1600, state of Adanse) while others date it to the reign of Oti Atenken (third chief of Asante). Asante lore says that the elderly woman Nana Amoah was the first ȯkyeame, as she was renowned for her eloquence. Upon her death, her son used her two walking sticks in her honor, carrying them while arguing state cases in front of the king. Prior to the creation of the representational form, aykeame used simple cylindrical staffs, sometimes covered with gold or silver foil, or the skin of the monitor lizard. These simple staffs took the name asɛmpa yɛ tia, a name equally used to refer to Amoah’s walking sticks and to the maxim “truth is brief.” The introduction of official government staffs (oban poma) by the colonial government of the British Gold Coast may have stimulated the creation of Akan staffs with representational designs. Often topped with decorative finials of lions or elephants, the British government gave these staffs to messengers and chiefs with whom they had official relationships. Highly ornamented staffs first appeared in the coastal Akan states in the 1890s, but did not take hold in Asante until the return of the exiled Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh I in 1924.

Ȯkyeame poma: a staff with symbolic meaning

The staff of office carried by aykeame are among the finest examples of the Akan verbal-visual nexus (Cole 1977, p. 9), drawing their iconography from a three-centuries-old pool of motifs that reflect the primacy of the elaborate spoken word in society. Frequently the visual expression of proverbs, staffs with representational finials enhance their holder’s speech. They achieve this by providing additional commentary through the use of easily recognizable iconography that expounds upon the power and nature of the chief. Held in the left hand during speechmaking, or carried while on other official duties, the staffs convey situationally appropriate messages. Most rulers employ multiple counsellors, each wielding a different staff. The enormous variety of motifs used on these staffs is only rivaled by those used in Akan goldweights.

Iconography

Peter Sarpong has identified the particular stool configuration used in this staff’s finial as an Akan chief’s stool (ahennwa) bearing the motif Asantehene adwa. This motif is generally associated with the Asante, the most populous and culturally influential Akan subgroup (Sarpong 1971, 65). As early as 1482, European sources documented stools associated with Akan royalty. The most famous example of an Akan stool—the Golden Stool of Asante (sika dwa kofi)—was created in the late seventeenth century. While domestic stools are omnipresent, it is the prerogative of the royals or other high-ranking persons to have ceremonial stools. These rival everyday seats not only in terms of spiritual significance, but also in terms of quality of carving, ornamentation, and material. The Akan believe that a ceremonial stool holds the soul of the ruler; as ahennwa can also refer to the soul of the nation, the stool can simultaneously refer to the ruler and to his chiefdom. Rulers are “enstooled,” and their stools blackened and stored for safekeeping upon their death.

Second in importance only to stools in Akan royal regalia, afena swords are ritual weapons held by the ruler during his enstoolment, or gripped by subchiefs who swear their allegiance to him. During processions, sword bearers flank the leader, who carries a small sword used as a dance wand. The form likely predates the Asante Empire (c. 1700–1900), as several examples entered European collections in the mid-seventeenth century, and were recorded in paintings from the era (see the example in the Ulmer Museum, accessioned before 1659, or Albert Eckhout’s 1641 oil painting of an African man in Brazil carrying an Akan sword, now at Copenhagen’s Nationalmuseet).

Interpretation

Like that of many akyeame poma, the carved finial on the Metropolitan’s example initially appears to be the visual representation of an Akan proverb, or at least an emblematic work that incorporates conventionalized imagery commonly associated with royal power. The presence of the stool—an object with royal connotations—means that the composition likely comments on the qualities of the ruler whom the ȯkyeame represented. However, no proverb has been definitively linked to this work. Given the regional specificity and elasticity of the meaning of proverbs, it may yet be identified. (See 1986.475a-c for an example of an Akan staff whose finial represents a proverb).

Moreover, not all staff imagery is linked to proverbs: history, lore, and current events may equally contribute to their diverse visual expression. Doran H. Ross’s interpretation of this object (2000), based on research in the National Archives in Ghana, clarifies why no proverb can be definitively linked to this work. This staff originally belonged to the head of Ghana’s Joint Provincial Council of Chiefs (JPC), a colonial-era governing body that linked three provinces of the British Gold Coast between 1936 and 1957. According to Ross, the staff incorporates imagery that evokes the three provinces of the council, represented here by three pillars or oil lamps bound together by a chain that unites them as a single political body. As cited by Peggy Appiah, chain motifs commonly reference the family and its unbreakable bonds. (Ross 1979, p. 94) D.A. Sutherland’s 1954 State Emblems of the Gold Coast confirms the identification of the motif as that of the Joint Provincial Council, and further elucidates its meaning. Both the three props and the three swords represents the three provinces (Eastern, Central and Western) that comprise the provincial councils; the stool represents both sovereignty and the dwelling place of the national soul; and finally, the chain represents how each province has been “welded into one single organization” known as the JPC. (Sutherland 1954, p. 5)

A witness to history

The staff was illustrated in the catalogue of Wrapped in Pride: Ghanaian Kente and African American Identity (1998, p 166, fig. 10.67). Taken by the Ghana Information Services, the photograph shows the staff (center) held by a figure identified as a ‘linguist’ attending Kwame Nkrumah, first prime minister and president of Ghana, on Ghana’s Independence Day (March 6, 1957). The figure holding the staff is thus likely a member (the head?) of the Joint Provincial Council. He has signified his role as a local leader within the colonial system of indirect rule through this easily recognizable Akan form. Alternatively, the man may be an ȯkyeame in the service of the JPC, or the government of the newly-independent Ghana. The use of the object for this purpose simultaneously evokes the earlier British practice of giving trusted Ghanaian figures staffs or canes to identify them, as well as the distinctly Akan use of representational staffs as both a signifier of position and governmental power. Wielded in a time of historic transition, its form evokes three major powers in Ghana’s history: the Asante, the British, and the independent nation.

Kristen Windmuller-Luna, 2015

Sylvan C. Coleman and Pam Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow in the Department of hte Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Published references

Ross, Doran H., and Agbenyega Adedze. Wrapped in Pride: Ghanaian Kente and African American Identity. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1998. p. 166, fig. 10.67

Further reading

Cole, Herbert M., and Doran H. Ross. The Arts of Ghana. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, 1977.

Kyerematen, Alex Atta Yaw. Kingship and Ceremony in Ashanti, Etc. Kumasi: UST Press, 1970.

Ross, Doran H. "The Verbal Art of Akan Linguist Staffs." African Arts 16, no. 1 (1982): 56-67+95-96.

Sarpong, Peter. The Sacred Stools of the Akan. Accra-Tema: [Ghana Pub. (Pub. Division)], 1971.

Yankah, Kwesi. Speaking for the Chief: Okyeame and the Politics of Akan Royal Oratory. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Artwork Details

- Title: Ȯkyeame poma (royal spokesperson's staff) with stool, chain, and crossed swords

- Artist: Asante-Akan artist

- Date: ca. 1930s

- Geography: Ghana

- Culture: Asante

- Medium: Wood, gold foil

- Dimensions: H. 63 7/8 x W. 4 3/8 x D. 3 5/8 in. (162.2 x 11.1 x 9.2 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: Gift of Drs. Herbert F. and Teruko S. Neuwalder, 1987

- Object Number: 1987.452.2a-c

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1565. Ȯkyeame poma (royal spokeperson’s staff) with stool, chain, and crossed swords, Asante-Akan artists

Kwame Anthony Appiah

KWAME ANTHONY APPIAH: Ȯkyeame—it’s the person who speaks for the paramount chief.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO (NARRATOR): Kwame Anthony Appiah, professor of philosophy and law at New York University, discusses the role of ȯkyeame, which is a spokesperson and royal counselor among the Akan, and their signature ceremonial staffs. The ȯkyeame uses rhetoric, including proverbs, to translate and augment complex ideas.

KWAME ANTHONY APPIAH: The word ȯkyeame means someone who greets. On more formal occasions the ȯkyeame would be the spokesperson for the king. So it’s a culture that valued the capacity to speak well in public, and it understood that in terms of being able to use the classical form of the language and to use it with reference to the great archive of oral tradition.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO: In Akan culture, the visual and the verbal are complementary. The ȯkyeame would have a collection of staffs to choose from depending on the occasion, with imagery that communicates as powerfully as the linguist’s words.

On the top of this staff, you’ll notice a carved finial with a ceremonial stool, chain, and swords.

KWAME ANTHONY APPIAH: A symbol can express an idea by instantiating something from a proverb, but it can just express an idea directly. So what you see there is the king and his kingship, represented by the stool, linked, chained together to the swords. So the idea is that the king and the lords are tied together, and that Asante is tied together. That everything holds together and is unified.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.