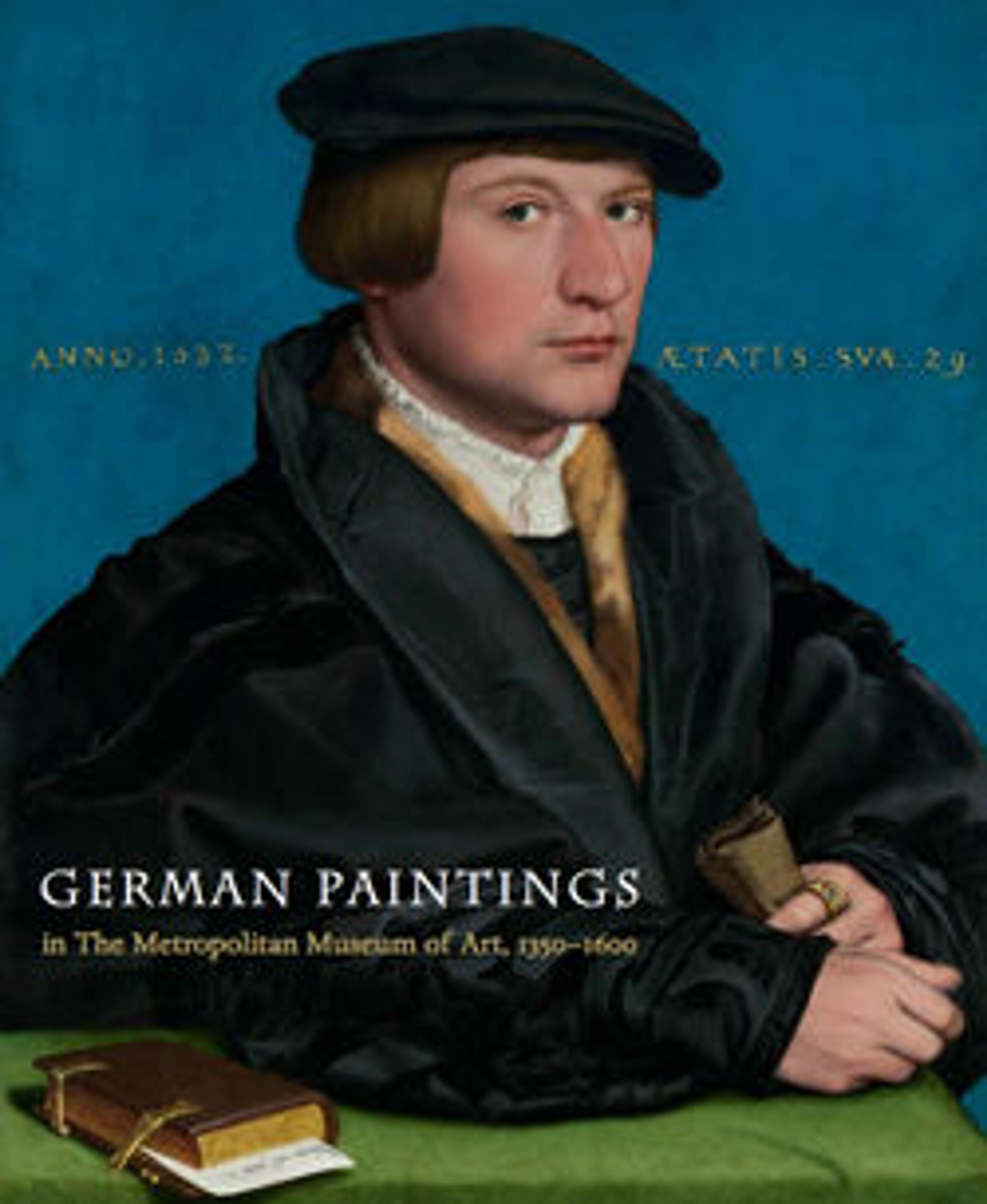

Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

Beham and his older brother Sebald were renowned as printmakers as well as painters. They were active in Nuremberg until 1525, when they were banished for opposing the Protestant Reformation. Barthel subsequently moved to Catholic Munich to serve as court painter to the Bavarian dukes William IV and Ludwig X. The sitter of this arresting portrait, Leonhard von Eck, was chancellor to William IV and a powerful opponent of the Reformation. An engraving after this portrait is inscribed with Leonhard von Eck’s name, his age (forty-seven), and the artist’s initials, with the date 1527.

Artwork Details

- Title: Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

- Artist: Barthel Beham (German, Nuremberg ca. 1502–1540 Italy)

- Date: 1527

- Medium: Oil on spruce

- Dimensions: 22 1/8 x 14 7/8 in. (56.2 x 37.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1912

- Object Number: 12.194

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.