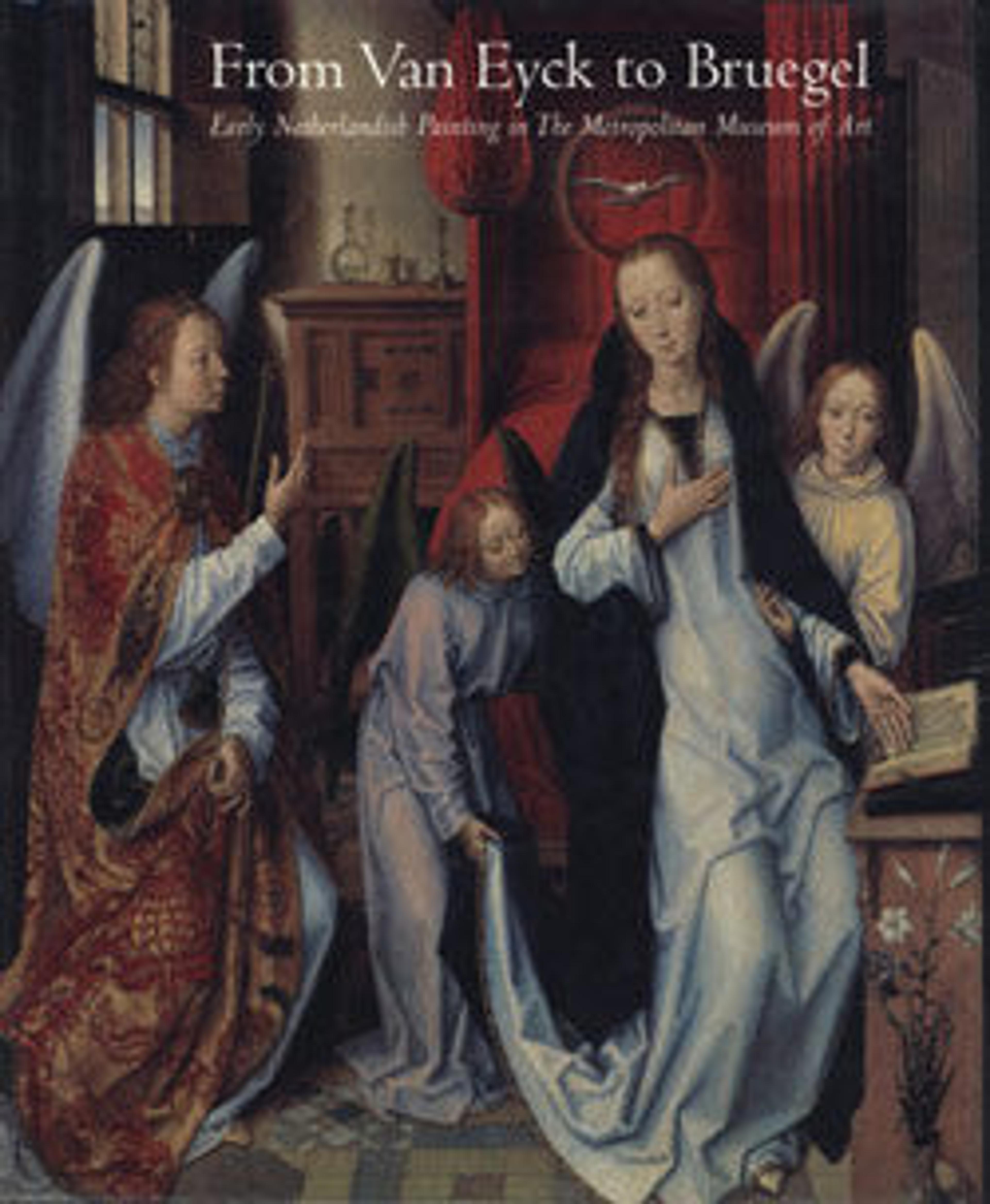

The Cellier Altarpiece

Saint Bernard, the standing monk seen on the left interior wing of this multipaneled altarpiece, was a reformer of the Cistercian order and a fervent proponent of the cult of the Virgin Mary. In this triptych he gathers with his family around her throne. The altarpiece was commissioned by Jeanne de Boubais for the Cistercian convent where she was abbess. She appears in the central panel in the guise of Saint Bernard’s sister, Humbeline, and for this reason wears the black Benedictine habit. Painted in grisaille on the exterior of the wings is Bernard’s vision of the Virgin, who miraculously wet the saint’s lips with her milk. This scene would have been visible when the wings of the altarpiece were closed.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Cellier Altarpiece

- Artist: Jean Bellegambe (French, Douai ca. 1470–1535/36 Douai)

- Date: 1511–12

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: Shaped top: central panel 40 x 24 in. (101.6 x 61 cm); left wing 37 3/4 x 10 in. (95.9 x 25.4 cm); right wing 37 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (95.3 x 24.1 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.102

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.