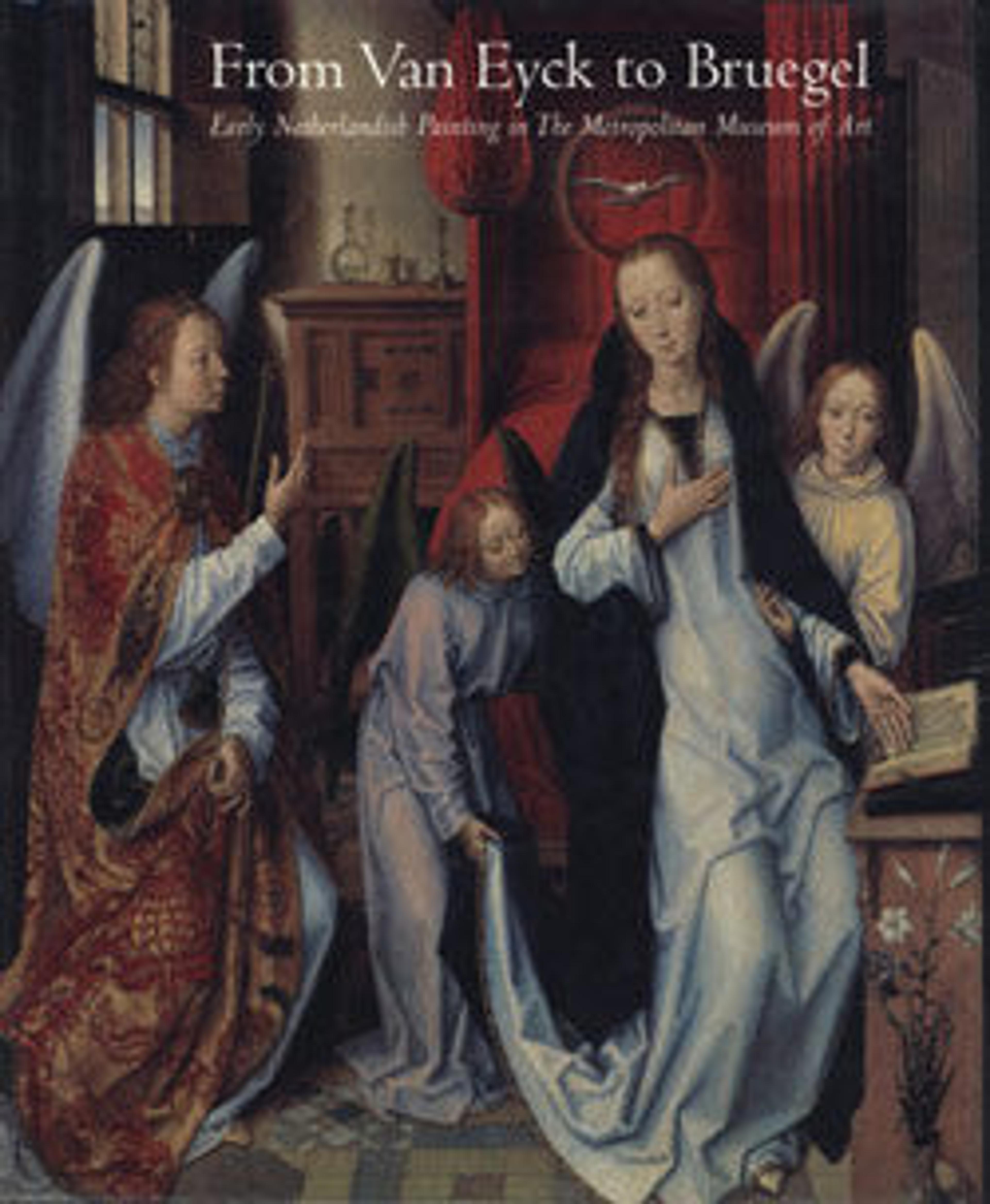

Virgin and Child

This is the finest surviving example by a workshop assistant of Dieric Bouts, based on a lost composition by the master himself. Among fifteen other versions of the subject, it is set apart from these by the panoramic landscape background that was probably not part of the prototype. The pink in the Child’s hand invests the painting with a double meaning, alluding to Mary’s sorrow over the Child’s earthly fate and the heavenly reunion of the two, thereby encapsulating his messianic role in the salvation of humankind and the Virgin’s sorrows and joys as the mother of Christ.

Artwork Details

- Title: Virgin and Child

- Artist: Workshop of Dieric Bouts (Netherlandish, Haarlem, active by 1457–died 1475)

- Date: 1475–99

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 11 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (29.2 x 21 cm); painted surface 11 1/4 x 7 3/4 in. (28.6 x 19.7 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982

- Object Number: 1982.60.16

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.