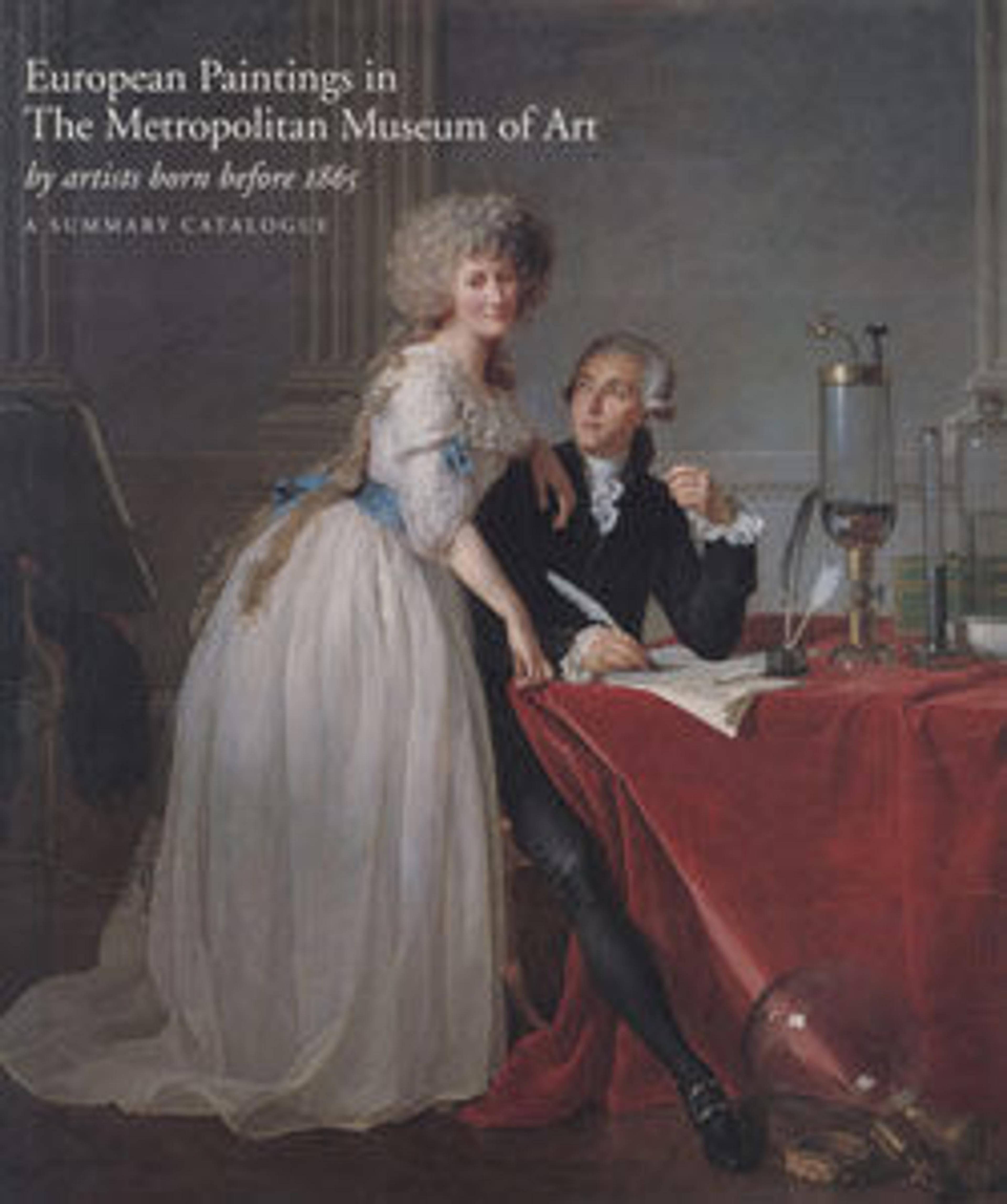

A Woman with a Dog

Ceruti was nicknamed “Pitocchetto” (the little beggar) due to his success painting sitters from the lower working class such as this woman, a maid carrying her employer’s dog. Candid and unidealized in her presentation, with her teeth visible, the woman would have struck contemporary viewers as unrefined, but her direct stare and confidently outstretched hand lend her an unusual degree of dignity. The spoiled dog, meanwhile, lampoons the gap between the maid’s circumstances and her employers’ comforts. A subtle play of pinks, whites, and greens further endows the subject with an elegance typically reserved for depictions of more socially elevated women.

Artwork Details

- Title: A Woman with a Dog

- Artist: Giacomo Ceruti (Italian, Milan 1698–1767 Milan)

- Date: 1740s

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 38 x 28 1/2 in. (96.5 x 72.4 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Maria DeWitt Jesup Fund, 1930

- Object Number: 30.15

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.