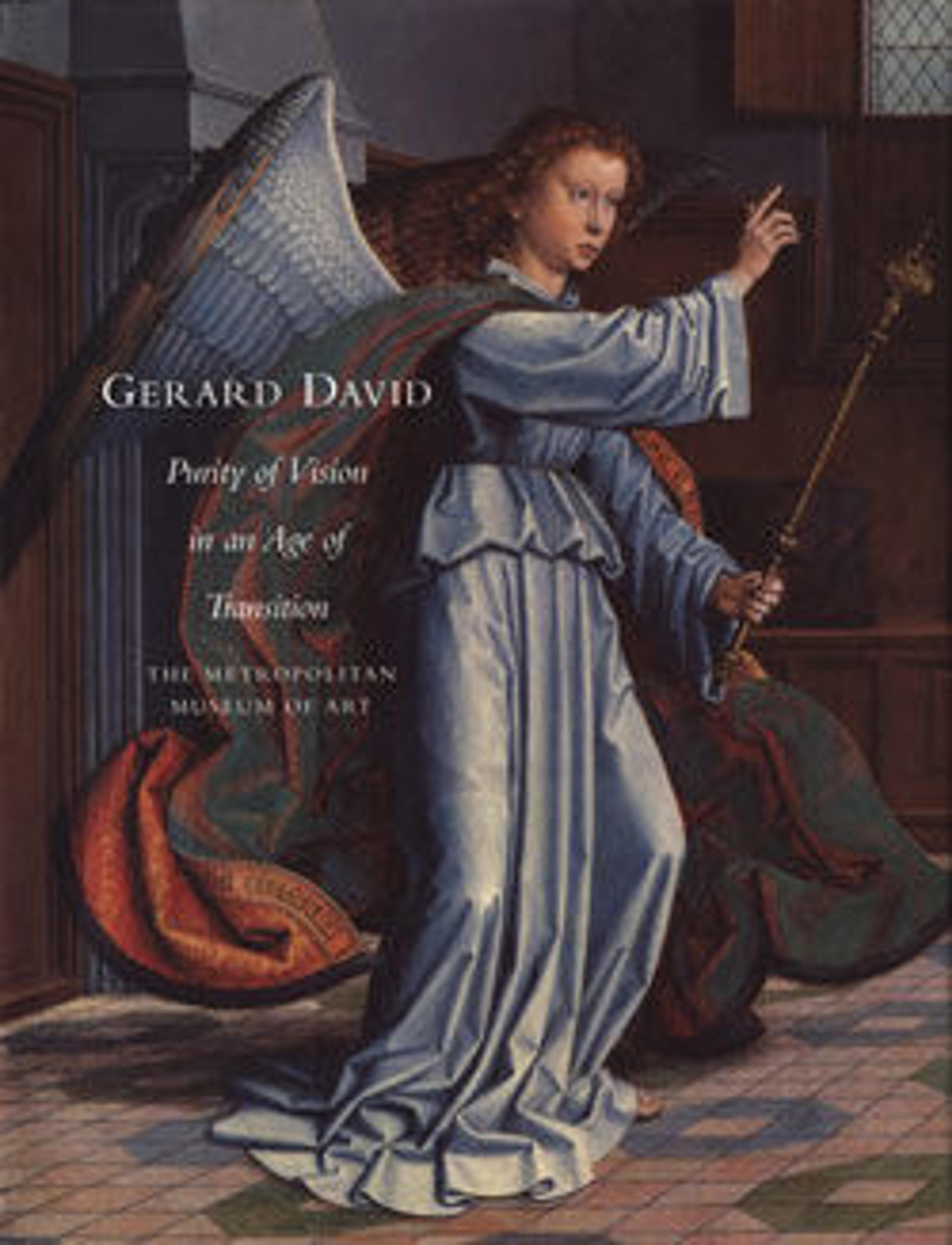

The Annunciation

These panels were part of a spectacular multistoried polyptych commissioned by Vincenzo Sauli, a wealthy Italian banker and diplomat with connections to Bruges, for the high altar of the Benedictine abbey church of San Gerolamo della Cervara, near Genoa. Taking the placement of the Annunciation within the altarpiece into account, David altered the perspective and the scale of the figures, since both panels were meant to be viewed from below. In style, the ensemble reveals a synthesis of Northern and Italian artistic modes that perhaps reflect the patron’s ties to both regions.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Annunciation

- Artist: Gerard David (Netherlandish, Oudewater ca. 1455–1523 Bruges)

- Date: 1506

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: Angel, overall 31 1/8 x 25 in. (79.1 x 63.5 cm), painted surface 30 1/4 x 24 3/8 in. (76.8 x 61.9 cm); Virgin, overall 31 1/8 x 25 1/4 in. (79.1 x 64.1 cm), painted surface 30 1/2 x 24 3/4 in. (77.5 x61.9 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950

- Object Number: 50.145.9ab

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

2621. The Annunciation

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.