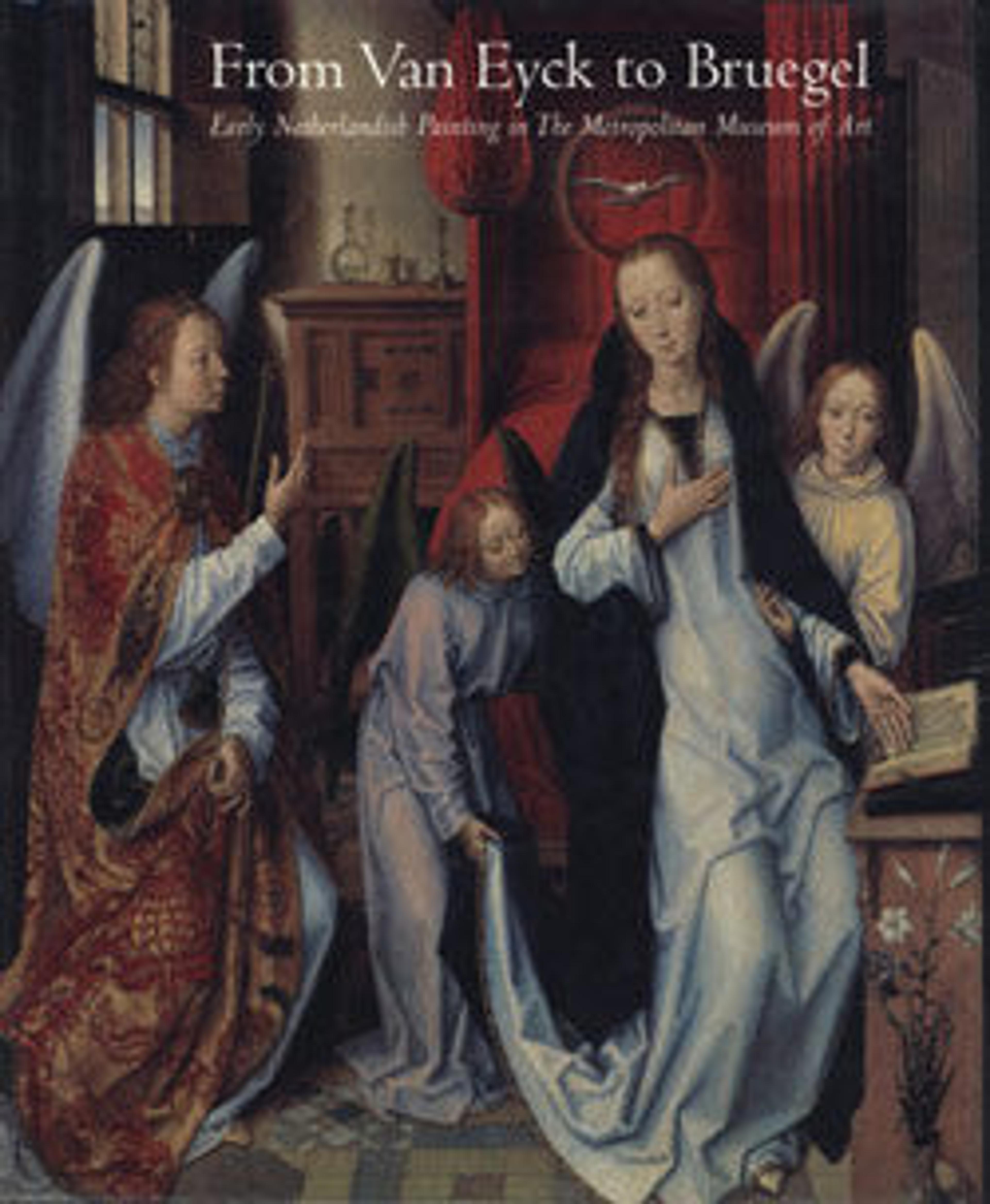

A Donor Presented by a Saint

Altarpieces were sometimes dismantled and cut into smaller fragments in later centuries. In this case, the original religious panel included a full-length portrait of the kneeling donor with his patron saint. At some point he was cut out from the waist up, and the background was repainted in a uniform, dark color to make the painting look like an independent portrait. With the overpaint now removed, the panel’s fragmentary condition is evident.

Artwork Details

- Title: A Donor Presented by a Saint

- Artist: Dieric Bouts (Netherlandish, Haarlem, active by 1457–died 1475)

- Date: ca. 1460–65

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 8 3/4 x 7 in. (22.2 x 17.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.41

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.