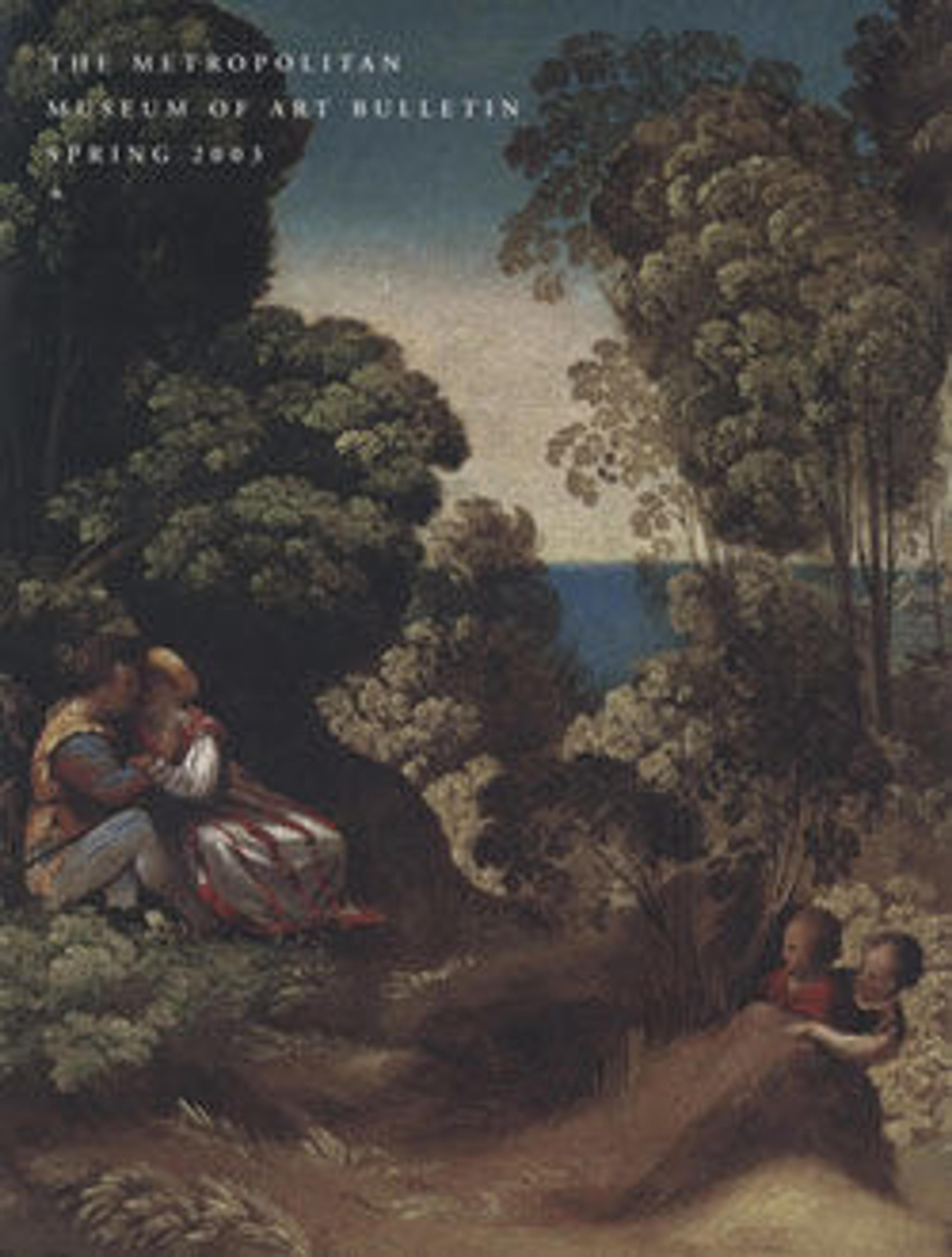

Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Jerome

Dating from about 1500–1510, this fine picture exemplifies the "sweetness and harmony of coloring" that made Francia a precursor of High Renaissance art. As with his contemporaries Perugino and Bellini, Francia was especially admired for what has been called a "devotional style" of painting, in which the refinement and delicacy of the technique and the serenity of the expressions made the picture an ideal focus for meditation and prayer.

Artwork Details

- Title: Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Jerome

- Artist: Francesco Francia (Italian, Bologna ca. 1447–1517 Bologna)

- Date: 1500–10

- Medium: Tempera on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 29 1/2 x 22 3/8 in. (74.9 x 56.8 cm); painted surface 27 1/2 x 22 1/4 in. (69.9 x 56.5 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941

- Object Number: 41.100.3

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.