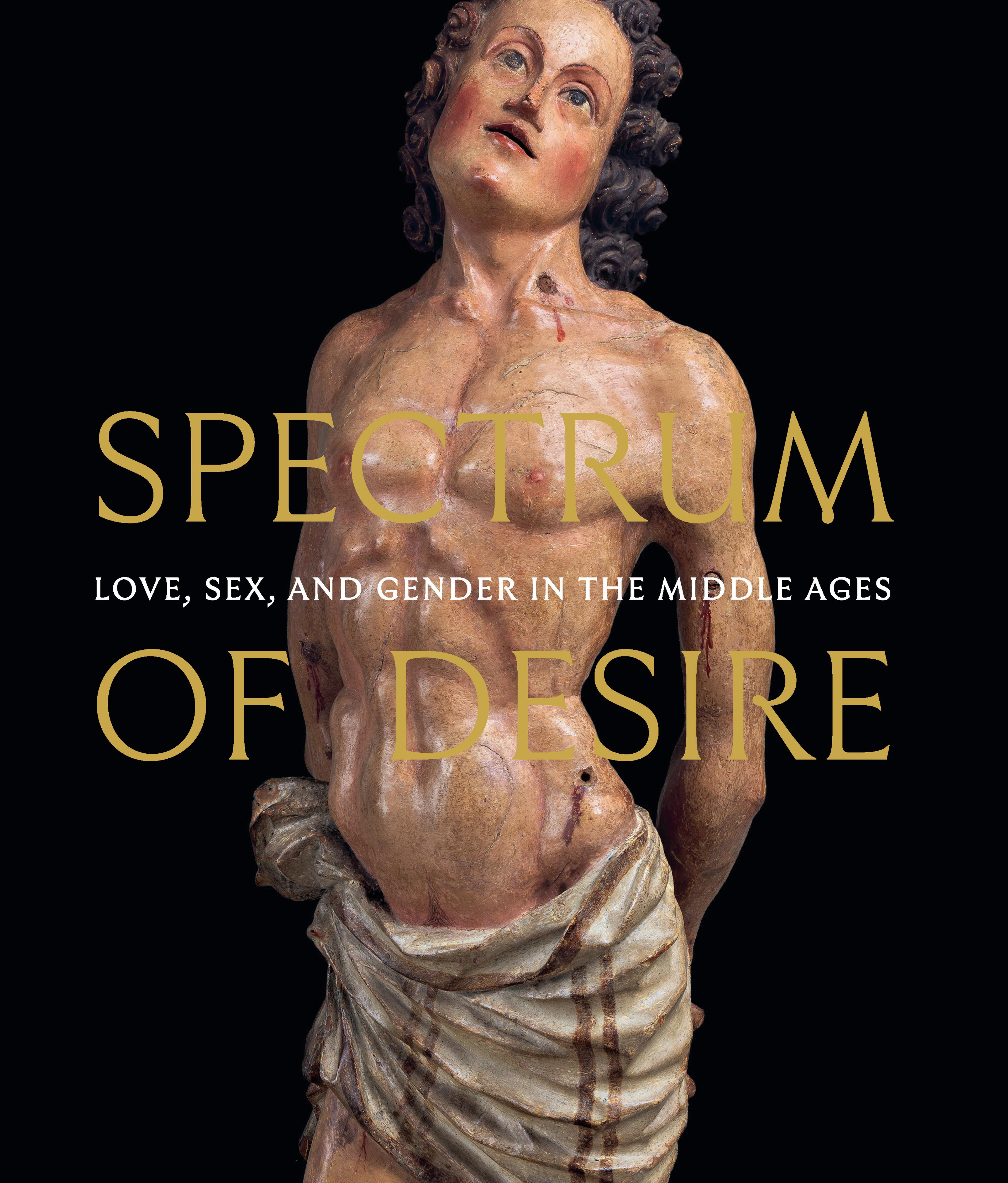

The Man of Sorrows

Depicted upright in his tomb, hands extended to display his wounds, this exquisitely rendered Jesus has been conceived as a focus for meditation. A diminutive Saint Francis receives the stigmata and becomes a surrogate for the viewer. Elaborately framed, with the reverse painted to imitate porphyry (a stone with imperial associations) this would have been a precious object of devotion, perhaps for a Franciscan friar. The pattern on the deteriorated background derives from Islamic textiles.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Man of Sorrows

- Artist: Michele Giambono (Michele Giovanni Bono) (Italian, active Venice 1420–62)

- Date: ca. 1430

- Medium: Tempera and gold on wood

- Dimensions: Overall, with engaged frame, 21 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (54.9 x 38.7 cm); painted surface 18 1/2 x 12 1/4 in. (47 x 31.1 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1906

- Object Number: 06.180

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

2639. Investigations: The Man of Sorrows, Part 1

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.