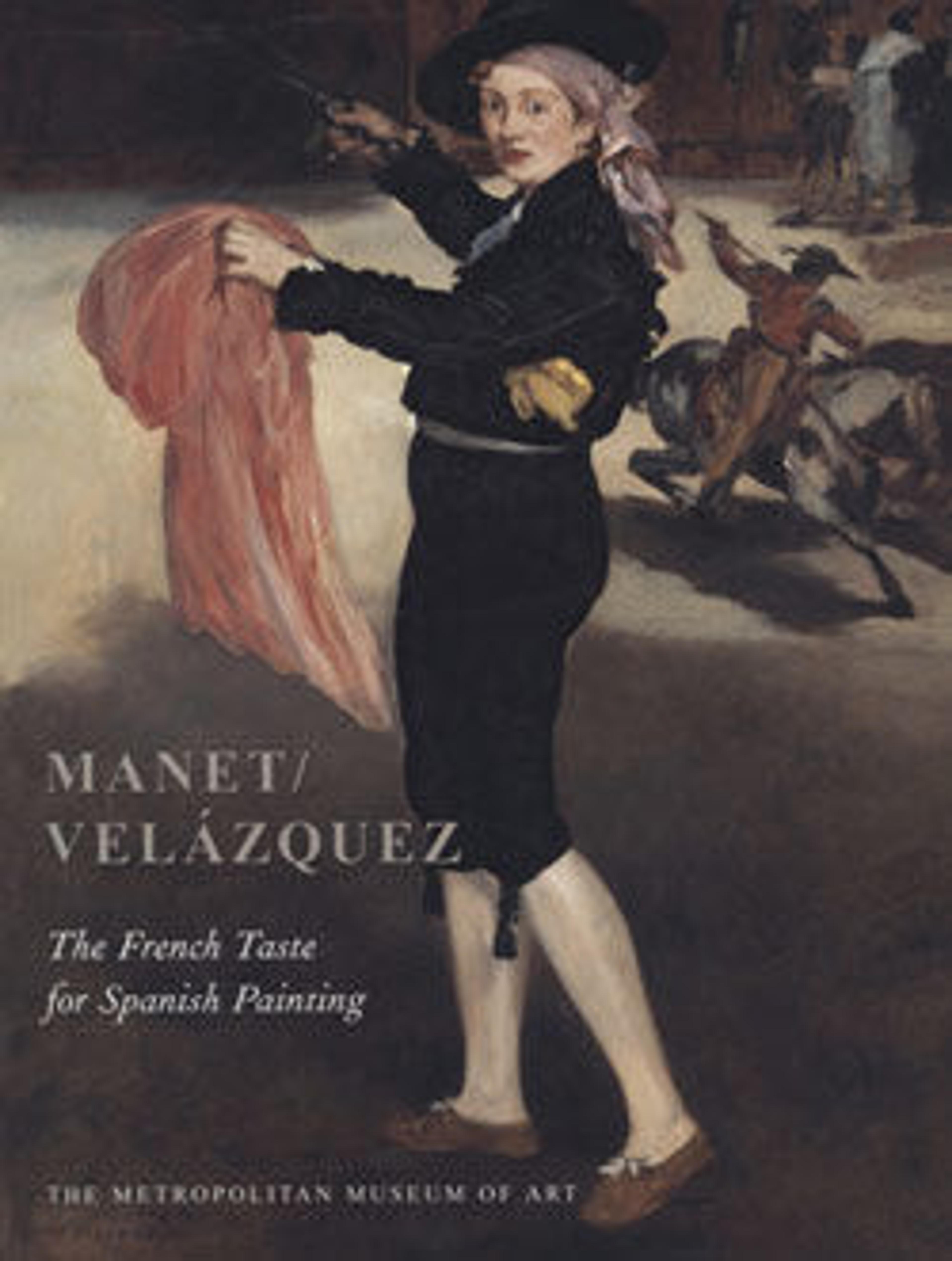

Majas on a Balcony

The women known as majas visually distinguished themselves through opulent, exaggerated traditional dress that became synonymous with Spanish popular culture. Goya’s innovative composition of majas on a balcony seen from the street—accompanied by somewhat threatening male companions—was one of his most well-known paintings and is today in a private collection. This version may be a variant that Goya used to explore different expressive and stylistic emphases, or it may have been painted by a close follower. Goya’s complex compositional device, in which balcony and picture plane overlap on the brink of public and private spaces, would inspire French painter Edouard Manet in his depictions of urban life in Paris during the late 1860s.

Artwork Details

- Title: Majas on a Balcony

- Artist: Attributed to Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux)

- Date: ca. 1800–1810

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 76 3/4 x 49 1/2in. (194.9 x 125.7cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929

- Object Number: 29.100.10

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.