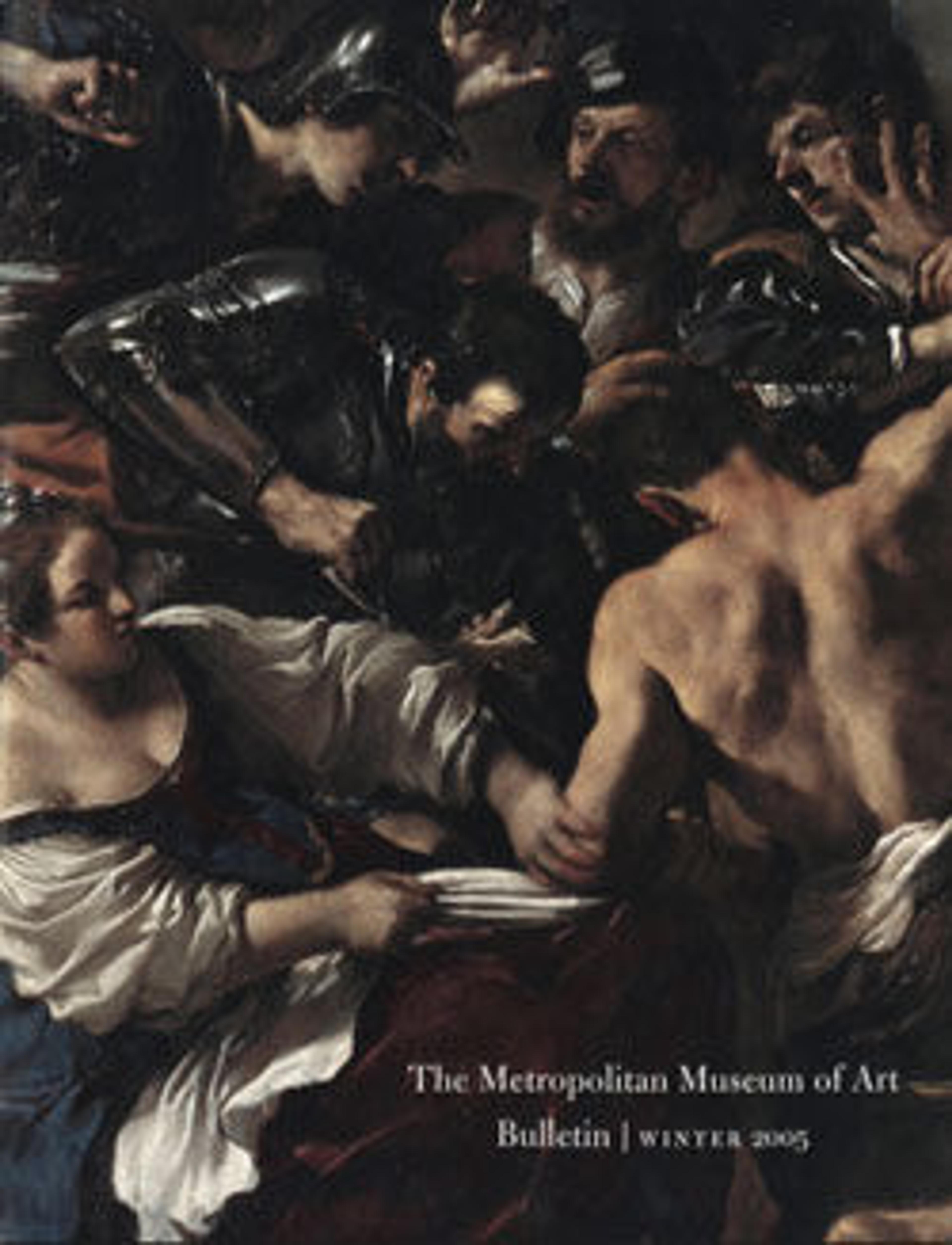

An Allegory

The fantastical subject of this painting has eluded scholars. The woman holding dividers over an open book with diagrams has been identified as Circe or Melissa, but is probably a more generic sorceress surrounded by symbols of her dark magic: skulls, a bat, and a chimera (a fantastical winged creature). The representation in the left foreground of a coati, a member of the raccoon family native to South America, is unique in early modern painting and was probably based on an animal living in a private zoo in Genoa.

Artwork Details

- Title:An Allegory

- Artist:Domenico Guidobono (Italian, Genoese, 1668–1746)

- Date:1710–20

- Medium:Oil on canvas

- Dimensions:56 3/4 x 92 1/4 in. (144.1 x 234.3 cm)

- Classification:Paintings

- Credit Line:Purchase, R. A. Farnsworth Gift, Gwynne Andrews, Charles B. Curtis, Rogers, Marquand, The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment, and Victor Wilbour Memorial Funds, 1970

- Object Number:1970.261

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.