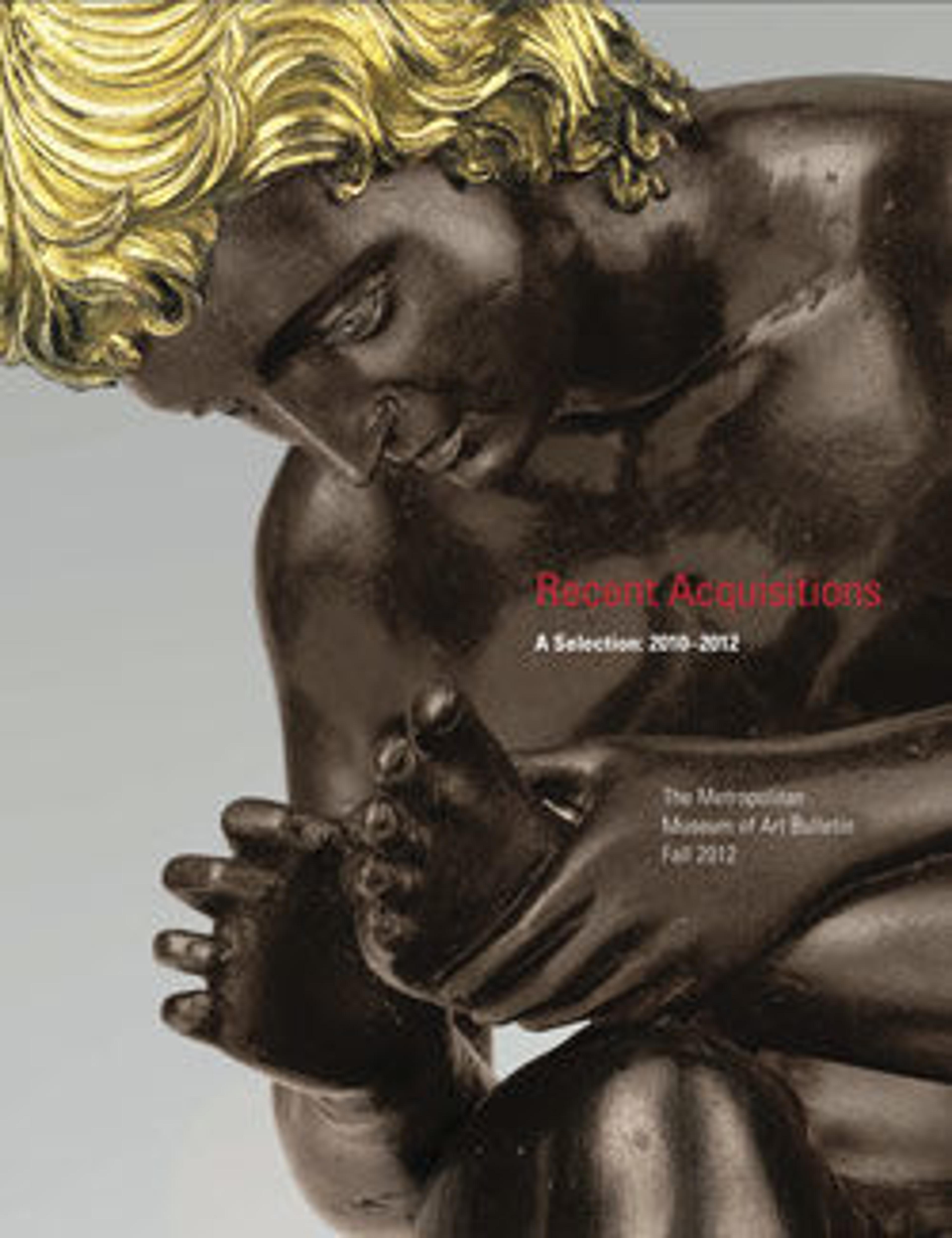

Self-Portrait

Born in Bohemia, today the Czech Republic, Mengs became an international celebrity, painting in Dresden, Rome, and Madrid in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. He was a rival to Pompeo Batoni, whose work hangs nearby, and a close friend of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whom he painted in the portrait also at The Met. Mengs’s depictions of prominent sitters are notable for their delicacy, but his images of himself are uncompromising and direct. He painted this self‑portrait, one of three known versions, in Madrid in 1776, by which time his health had begun to fail. A symptom of his illness is seen in the discolored swelling on his forehead.

Artwork Details

- Title: Self-Portrait

- Artist: Anton Raphael Mengs (German, Ústi nad Labem (Aussig) 1728–1779 Rome)

- Date: 1776

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 35 1/2 x 25 7/8 in. (90 x 65.5 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 2010

- Object Number: 2010.445

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.