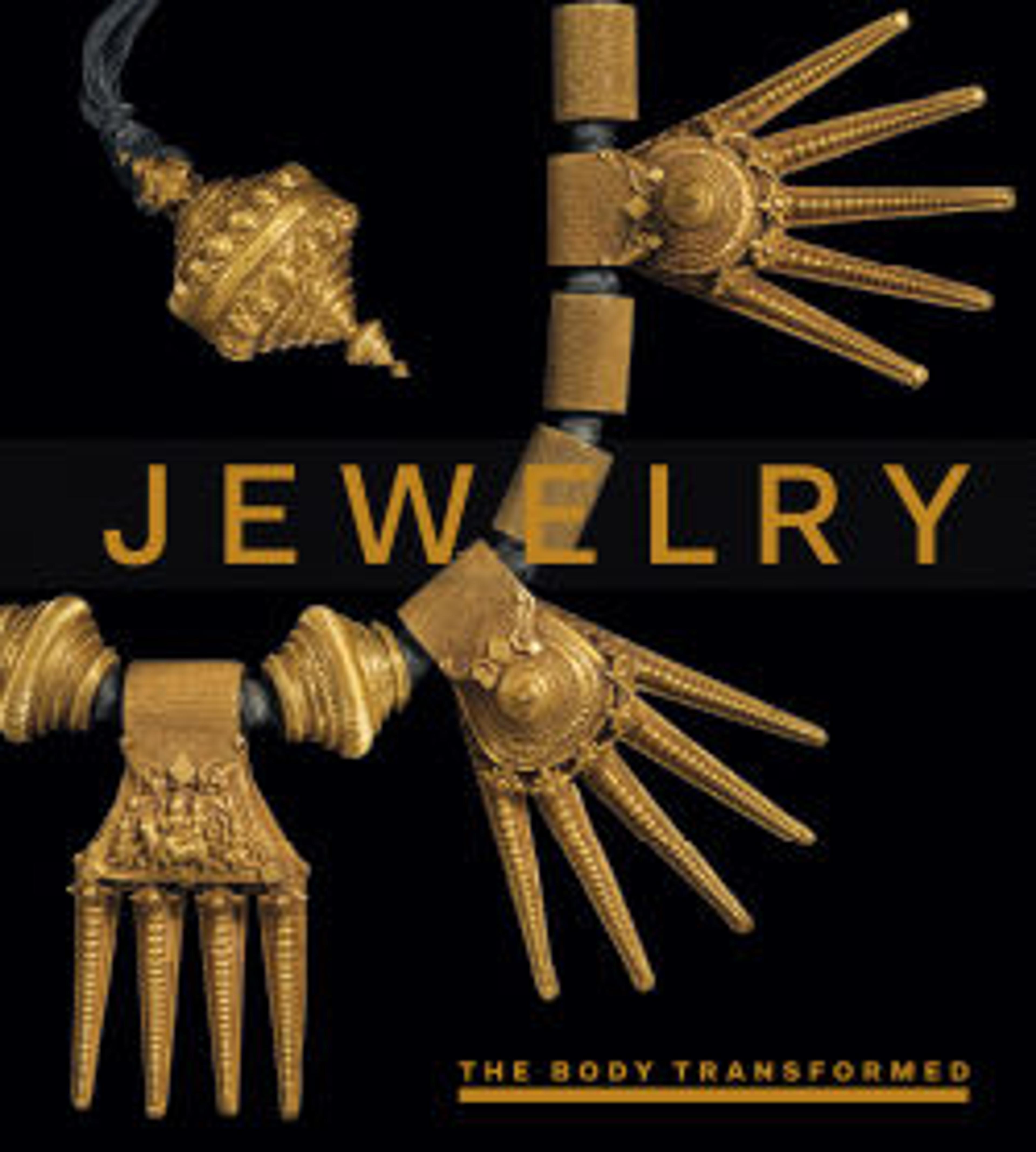

Head Ornament

This head ornament would attach at the top of the head, and the flower and bell-shaped ornaments known as karnaphul jhumka would hang along the side of the ear. The karnaphul, or floral stud, is a typical shape for an ear ornament, referencing the natural world so favored in Indian jeweled arts. The hanging bell-shaped jhumka pendants would move gracefully as the wearer walked, moved, and danced.

This ornament was formerly in the collection of American artist and designer Lockwood de Forest (1850–1932) who purchased many items while traveling in India between 1879–1881. He collected many different examples of jewelry from India, including several of the same type. Today, his assemblage in the Met serves as a near-comprehensive study collection of Indian jewelry from the late nineteenth century.

This ornament was formerly in the collection of American artist and designer Lockwood de Forest (1850–1932) who purchased many items while traveling in India between 1879–1881. He collected many different examples of jewelry from India, including several of the same type. Today, his assemblage in the Met serves as a near-comprehensive study collection of Indian jewelry from the late nineteenth century.

Artwork Details

- Title: Head Ornament

- Date: 19th century

- Geography: Attributed to India, Kashmir, Punjab, or Rajasthan

- Medium: Gold, glass, turquoise

- Dimensions: Ht. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm)

W. 10 5/8 in. (27 cm)

D. 1 9/16 in. (4 cm) - Classification: Jewelry

- Credit Line: John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915

- Object Number: 15.95.105

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.