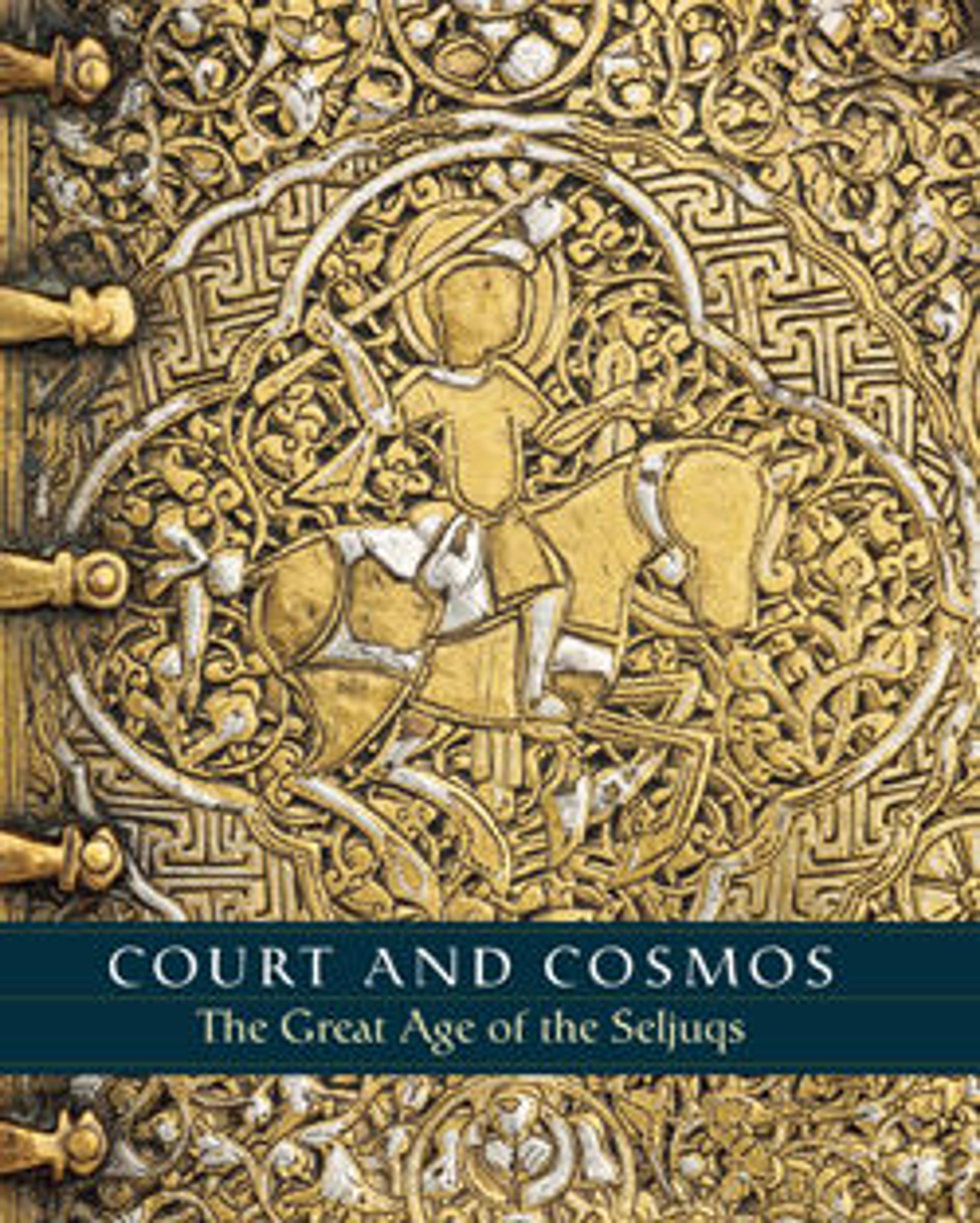

Panel from a Mosque Frieze Bearing the Name of a Sultan

This panel and the other five in the Met’s collection (39.40.60–64) were excavated near a mosque that served a dense residential neighborhood in medieval Nishapur. Together with other panels now in Iran, they are believed to have framed the entrance portal of the prayer hall. The frieze was originally painted in red and lapis blue on a white ground. It included the word "al-sultan", a title that first occurred in monumental epigraphy in the eleventh century with Seljuq and Ghaznavid rulers.This inscription originally bore the titles of the Seljuq Sultan Malik Shah (r. 1073–92).

In this period Nishapur was a thriving center of religious and intellectual life that prospered due to its position on the trade route to Central Asia, natural resources such as turquoise and alabaster, the cultivation of cotton, and the production of both silk and cotton textiles.

In this period Nishapur was a thriving center of religious and intellectual life that prospered due to its position on the trade route to Central Asia, natural resources such as turquoise and alabaster, the cultivation of cotton, and the production of both silk and cotton textiles.

Artwork Details

- Title: Panel from a Mosque Frieze Bearing the Name of a Sultan

- Date: 11th century

- Geography: Excavated in Iran, Nishapur

- Medium: Terracotta; carved, painted

- Dimensions: H. 23 5/8 in. (60 cm)

W. 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm)

D. 4 1/8 in. (10.5 cm)

Wt. 74 lbs. (33.6 kg) - Classification: Sculpture

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1939

- Object Number: 39.40.58

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.