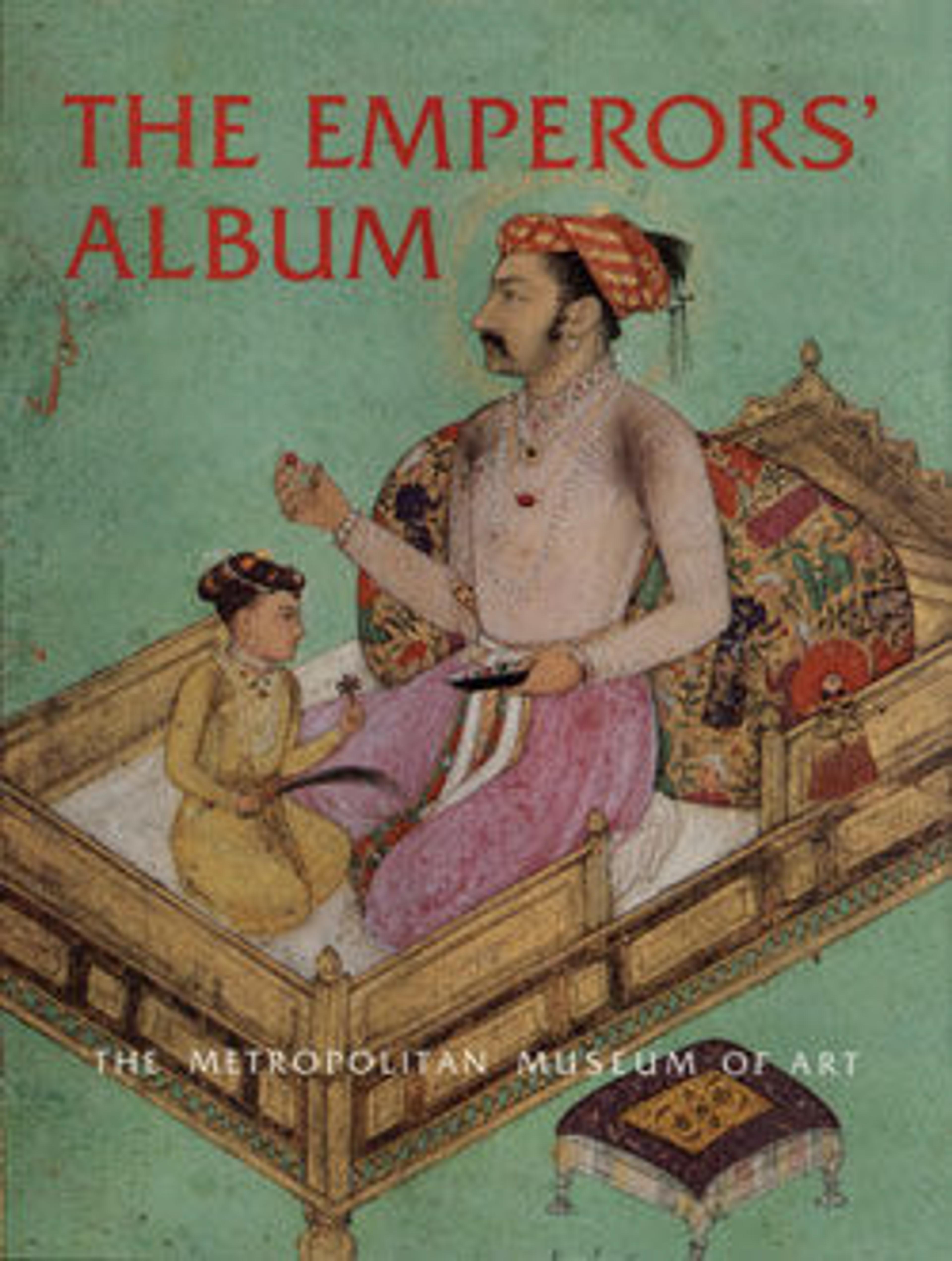

"Four Portraits: (upper left) A Raja (Perhaps Raja Sarang Rao), by Balchand; (upper right) 'Inayat Khan, by Daulat; (lower left) 'Abd al-Khaliq, probably by Balchand; (lower right) Jamal Khan Qaravul, by Murad", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

These portraits were made for Jahangir (r. 1605–27), whose painters, while technically flawless, were able to reveal the nuances of characterization. 'Inayat Khan, a favorite courtier, is remembered today from two portraits made as he lay at death’s door, emaciated from his addiction to opium and wine, though here he appears healthy. 'Abd al-Khaliq met his death after siding with Shah Jahan against his father. Jamal Khan Qaravul was a minor nobleman, and the identification of the raja, in Jahangir’s handwriting, is illegible.

Artwork Details

- Title: "Four Portraits: (upper left) A Raja (Perhaps Raja Sarang Rao), by Balchand; (upper right) 'Inayat Khan, by Daulat; (lower left) 'Abd al-Khaliq, probably by Balchand; (lower right) Jamal Khan Qaravul, by Murad", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

- Artist: Painting by Balachand (active 1595–ca. 1650)

- Artist: Painting by Daulat (Indian, active ca. 1595–1635)

- Artist: Painting by Murad

- Date: recto: ca. 1610–15; verso: dated 1541

- Geography: Attributed to India

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: Overall page: H. 15 3/16 in. (38.6 cm)

W. 10 3/16 in. (25.9 cm)

Painting inside border: H. 11 1/2 in. (29.2 cm)

W. 8 7/8 in. (22.5 cm)

All four portraits: H. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm)

W. 5 3/16 in. (13.2 cm)

Portrait (top left): Ht. 5 5/16 in. (13.5 cm)

W. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm)

Portrait (top right): Ht. 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm)

W. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm)

Portrait (bottom left): Ht. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm)

W. 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm)

Portrait (bottom right): Ht. 4 7/16 in. (11.3 cm)

W. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955

- Object Number: 55.121.10.29

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.