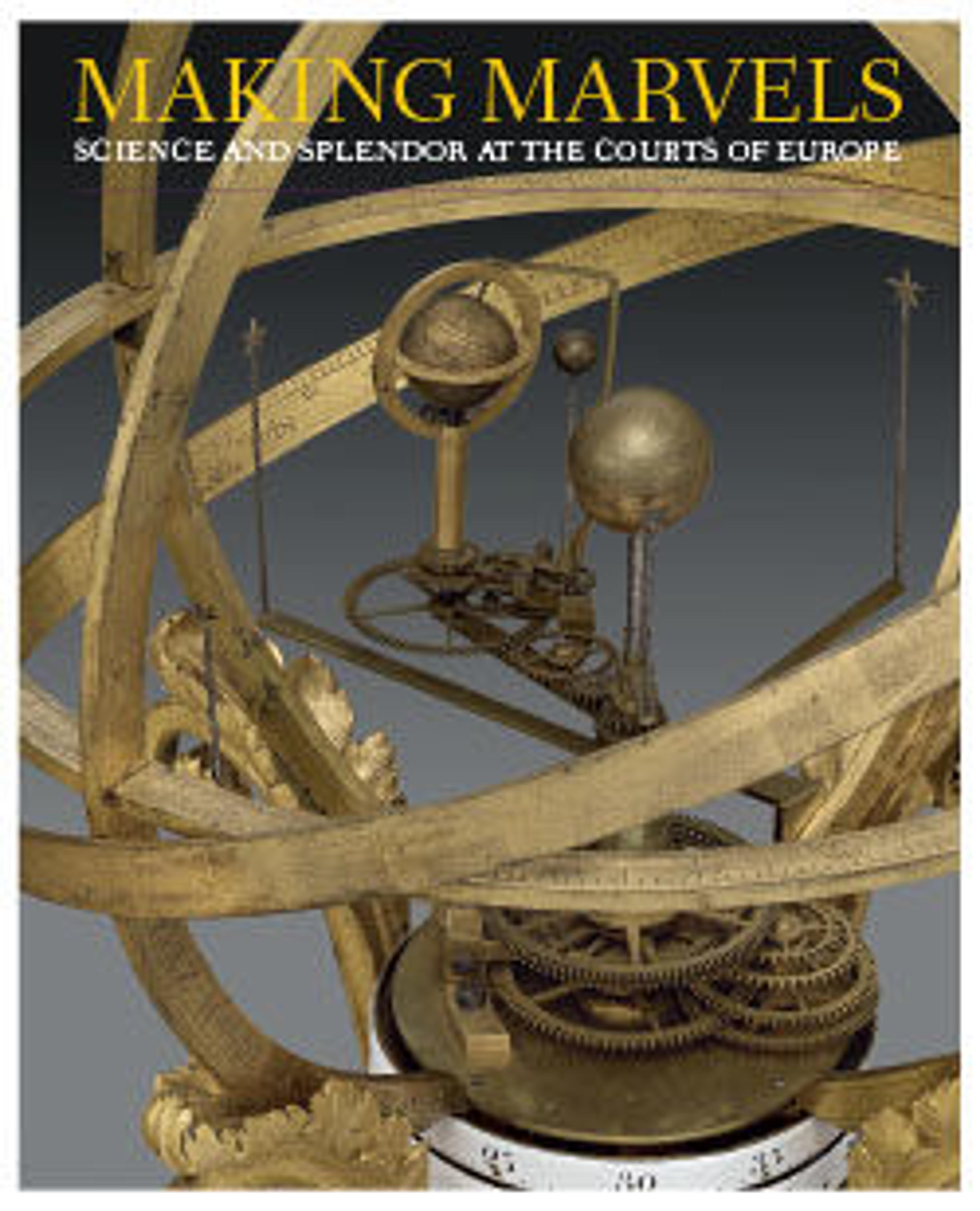

Planispheric Astrolabe

Artwork Details

- Title: Planispheric Astrolabe

- Maker: Muhammad Zaman al-Munajjim al-Asturlabi (Iranian, active 1643–1689)

- Date: dated 1065 AH/1654–55 CE

- Geography: Attributed to Iran, Mashhad

- Medium: Brass and steel; cast and hammered, pierced and engraved

- Dimensions: H. 8 1/2 in. (21.6 cm)

W. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm)

D. 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm) - Classification: Metal

- Credit Line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963

- Object Number: 63.166a–j

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

1162. Kids: Planisperic Astrolabe

NAVINA HAIDAR: We’re looking at the metal object that’s shaped mostly like a circle - with a pointed arch shape, and a loop, at the top. On the front of it is a dial with very complicated markings. Do you see all the thin dark markings, even around the edge? This is a scientific instrument for studying stars and planets – but it’s decorated as an object of art, as well! It’s called an astrolabe. To use it, you’d hold the astrolabe up with the thumb of one hand with the loop at the top, and look through a tube on the back of it – gazing at a particular star. Then you’d move the dials on the front to figure out the location of other stars and planets on that day. Astrolabes were really important tools for medieval astronomers. Astronomy was an advanced science in the Islamic world in general. In the Islamic world astrolabes also helped people figure out the correct times and direction to face for their daily prayers.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.