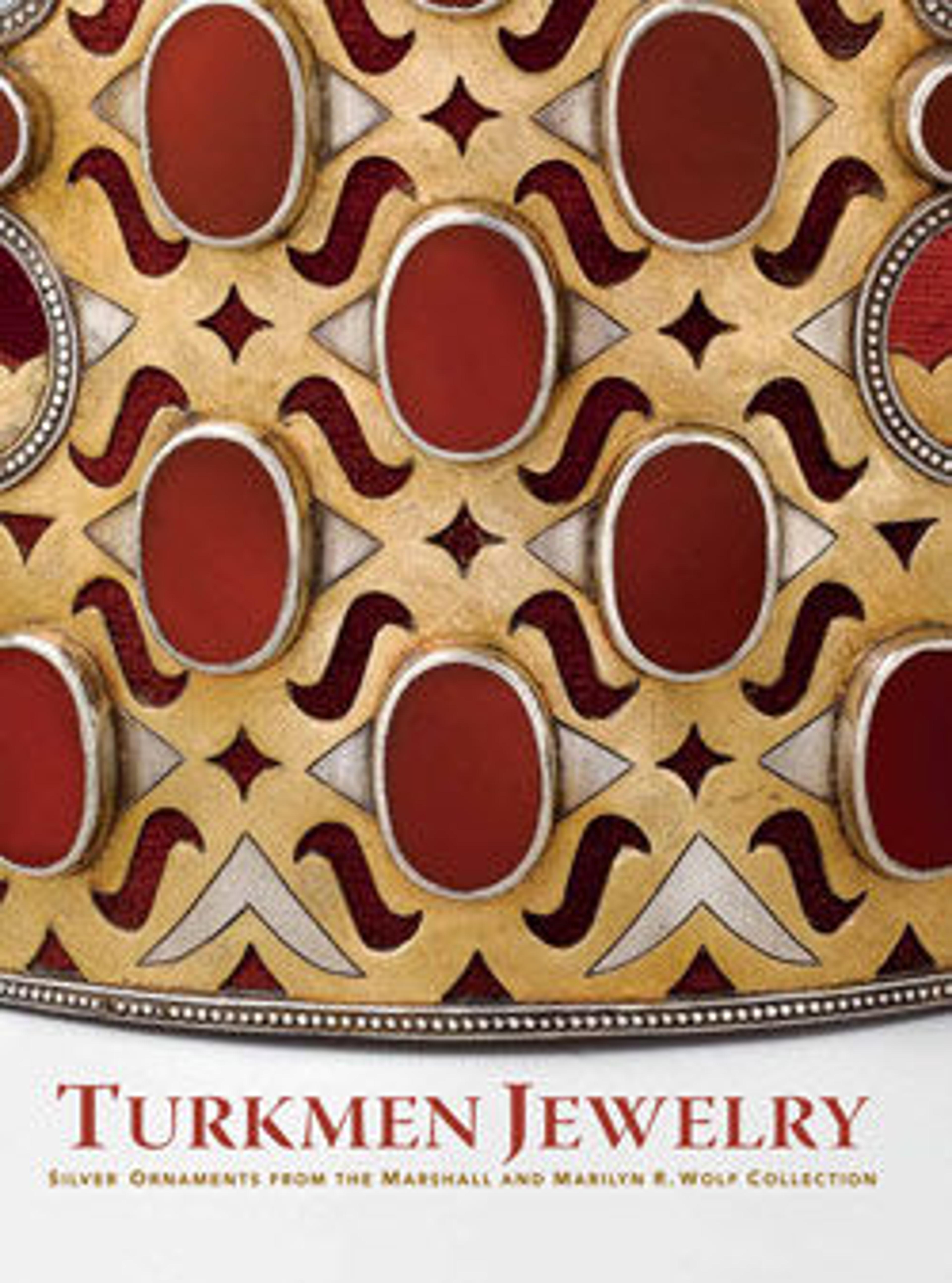

Cordiform Pendant

Dorsal ornaments in heart-shaped or ashik form are common in Turkman jewelry. They often hung from the wearer's head and extended onto their backs. This example is distinguished by its imposing size, its sophisticated openwork at the center (usually plain) and the cylindrical tube or tumar used to hold talismanic Muslim prayer scrolls that crowns the piece.

Artwork Details

- Title: Cordiform Pendant

- Date: probably 20th century

- Geography: Attributed to Turkmenistan

- Medium: Silver; fire gilded and chased, with openwork, cabochon and table-cut carnelians, and embossed terminals

- Dimensions: H. 18 1/2 in. (47 cm)

W. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm) - Classification: Jewelry

- Credit Line: Gift of Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf, 2005

- Object Number: 2005.443.1

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.