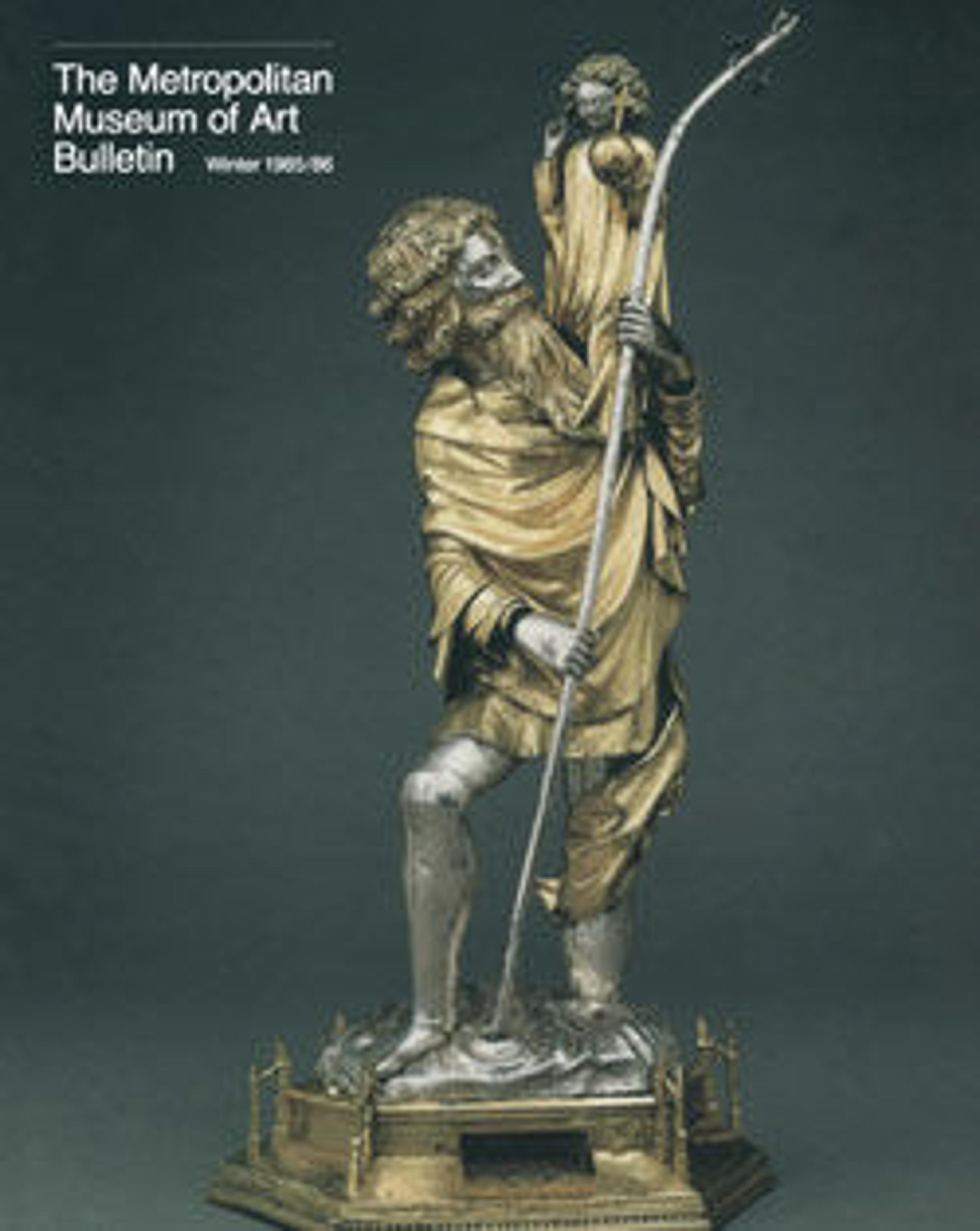

Crozier with Lamb of God

The crozier was the pastoral staff based on the shepherd's crook and carried by bishops, abbots, and abbesses. This example belongs to a group of objects made in northern Italy. This crozier was originally made in sections with threaded ends. The three sections here have been damaged and repaired and are no longer separable. There may have been a fourth section, which is now lost.

Artwork Details

- Title: Crozier with Lamb of God

- Date: ca. 1360–1400

- Geography: Made in possibly the Lagoon destrict of Venice, Italian

- Culture: North Italian

- Medium: Bone with paint and gold

- Dimensions: Overall: 61 x 9 9/16 x 2 7/16 in. (154.9 x 24.3 x 6.2 cm)

- Classification: Ivories-Bone

- Credit Line: The Cloisters Collection, 1953

- Object Number: 53.63.4

- Curatorial Department: Medieval Art and The Cloisters

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.