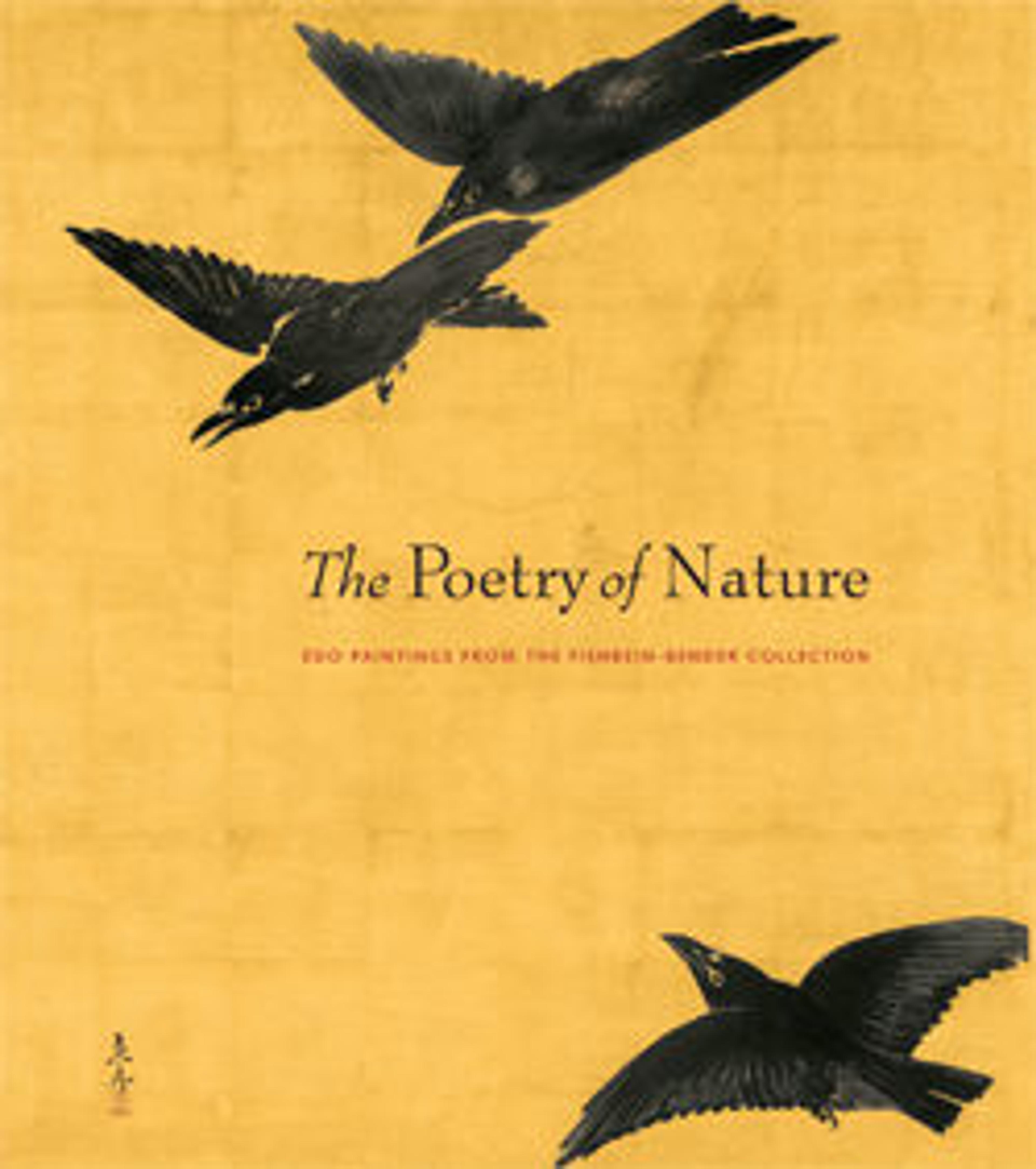

Bo Ya Plays the Qin as Zhong Ziqi Listens

The Liezi, a fourth-century Daoist text, records the story of Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqi, scholars renowned for their devotion to each other. Bo Ya, an accomplished player of the qin, a type of zither, would frequently play for his friend Zhong, himself a musician who truly appreciated his friend’s music. When Zhong died, however, the bereaved Bo Ya deliberately broke his instrument, never to play again.

Likely once part of a set of sliding-door panels (fusuma), this painting depicts Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqi taking shelter from a storm beneath a cliff, where Bo Ya plays his qin to pass the time. The work bears no seal or signature but exemplifies the formal landscape style of the early Kano school and was traditionally attributed to the school’s founder, Motonobu. Discrepancies with Motonobu’s accepted style, however, suggest that the artist was active in Motonobu’s circle, probably during the 1530s.

Likely once part of a set of sliding-door panels (fusuma), this painting depicts Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqi taking shelter from a storm beneath a cliff, where Bo Ya plays his qin to pass the time. The work bears no seal or signature but exemplifies the formal landscape style of the early Kano school and was traditionally attributed to the school’s founder, Motonobu. Discrepancies with Motonobu’s accepted style, however, suggest that the artist was active in Motonobu’s circle, probably during the 1530s.

Artwork Details

- 狩野元信周辺 伯牙鍾子期図

- Title: Bo Ya Plays the Qin as Zhong Ziqi Listens

- Artist: Circle of Kano Motonobu (Japanese, 1477–1559)

- Period: Muromachi period (1392–1573)

- Date: 1530s

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper

- Dimensions: Image: 65 1/16 × 34 1/4 in. (165.2 × 87 cm)

Overall with mounting: 8 ft. 10 7/8 in. × 40 13/16 in. (271.5 × 103.7 cm)

Overall with knobs: 8 ft. 10 7/8 in. × 43 3/16 in. (271.5 × 109.7 cm) - Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015

- Object Number: 2015.300.67

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.