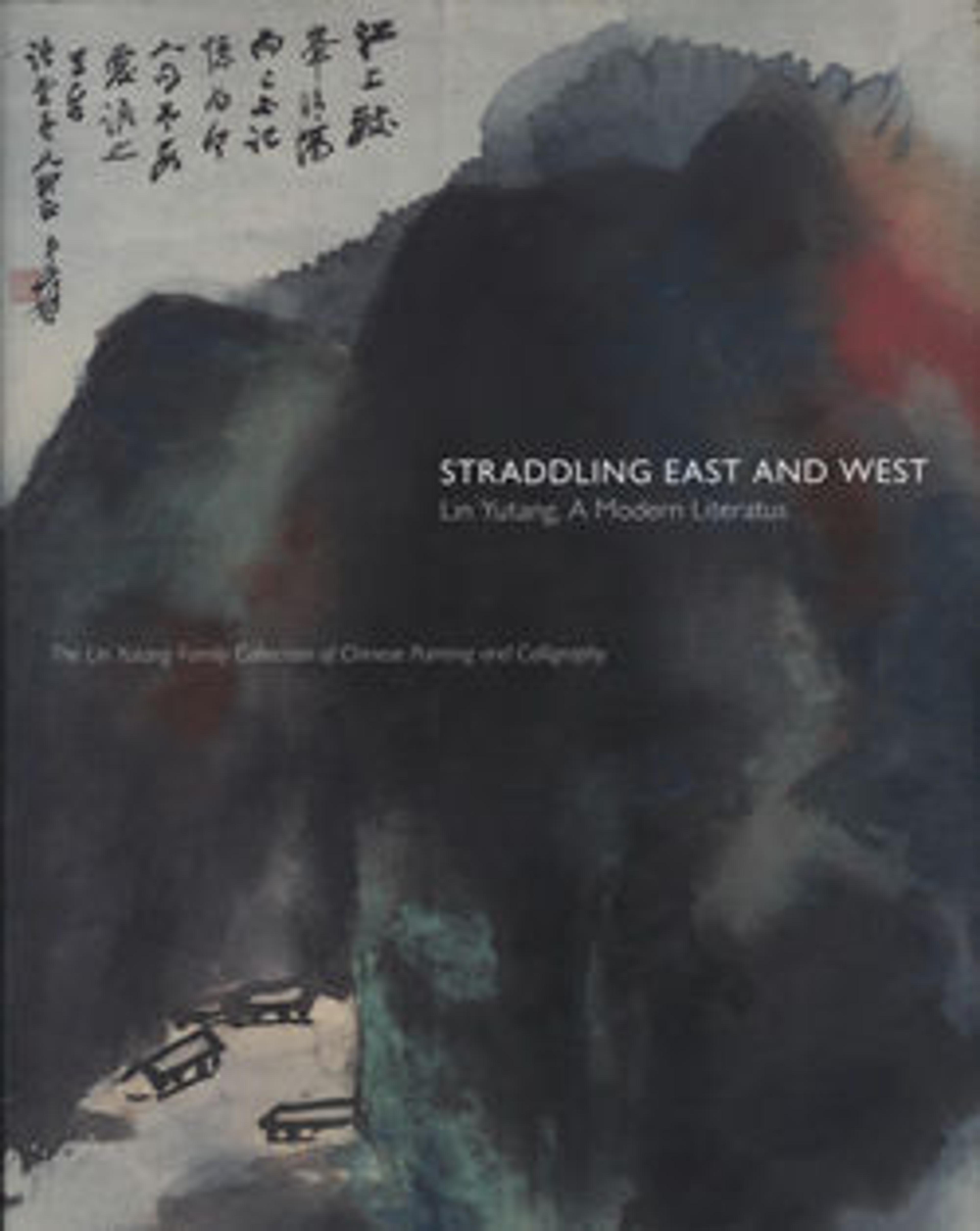

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering

Wang Yunwu made significant contributions to publishing, library science, and education reform in twentieth century China. He was also a capable calligrapher, as his transcription of Wang Xizhi's (303–361) "Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering" here demonstrates. Revered by calligraphers as the greatest work in running script, this legendary text was composed by Wang on the third day of the third lunar month in 353, when forty-one eminent men of letters gathered at the Orchid Pavilion, a scenic site near Wang's hometown of Shanyin in northern Zhejiang, to perform the customary purification ritual held on that day. During the celebration, all the participants composed poems, and Wang brushed his famous preface. Half inebriated, he created a calligraphic masterpiece so extraordinary that even he could never equal it.

Wang Xizhi's "Preface" has also been widely admired for its literary finesse and depth of feeling. Lin Yutang translated the entire text in his The Importance of Living (1937), praising it for embodying a very Chinese response to the "evanescence of life." Because Wang Yunwu's transcription makes no allusion to Wang Xizhi's style, he presumably shared Lin's appreciation of the philosophic import of the "Preface."

Wang Xizhi's "Preface" has also been widely admired for its literary finesse and depth of feeling. Lin Yutang translated the entire text in his The Importance of Living (1937), praising it for embodying a very Chinese response to the "evanescence of life." Because Wang Yunwu's transcription makes no allusion to Wang Xizhi's style, he presumably shared Lin's appreciation of the philosophic import of the "Preface."

Artwork Details

- 近代 王雲五 草書蘭亭序 軸

- Title: Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering

- Artist: Wang Yunwu (Chinese, 1888–1979)

- Date: dated 1964

- Culture: China

- Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

- Dimensions: Image: 59 1/16 x 16 13/16 in. (150 x 42.7 cm)

Overall with knobs: 83 1/16 x 21 1/16 in. (211 x 53.5 cm) - Classification: Calligraphy

- Credit Line: The Lin Yutang Family Collection, Gift of Richard M. Lai, Jill Lai Miller, and Larry C. Lai, in memory of Taiyi Lin Lai, 2005

- Object Number: 2005.509.11

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.