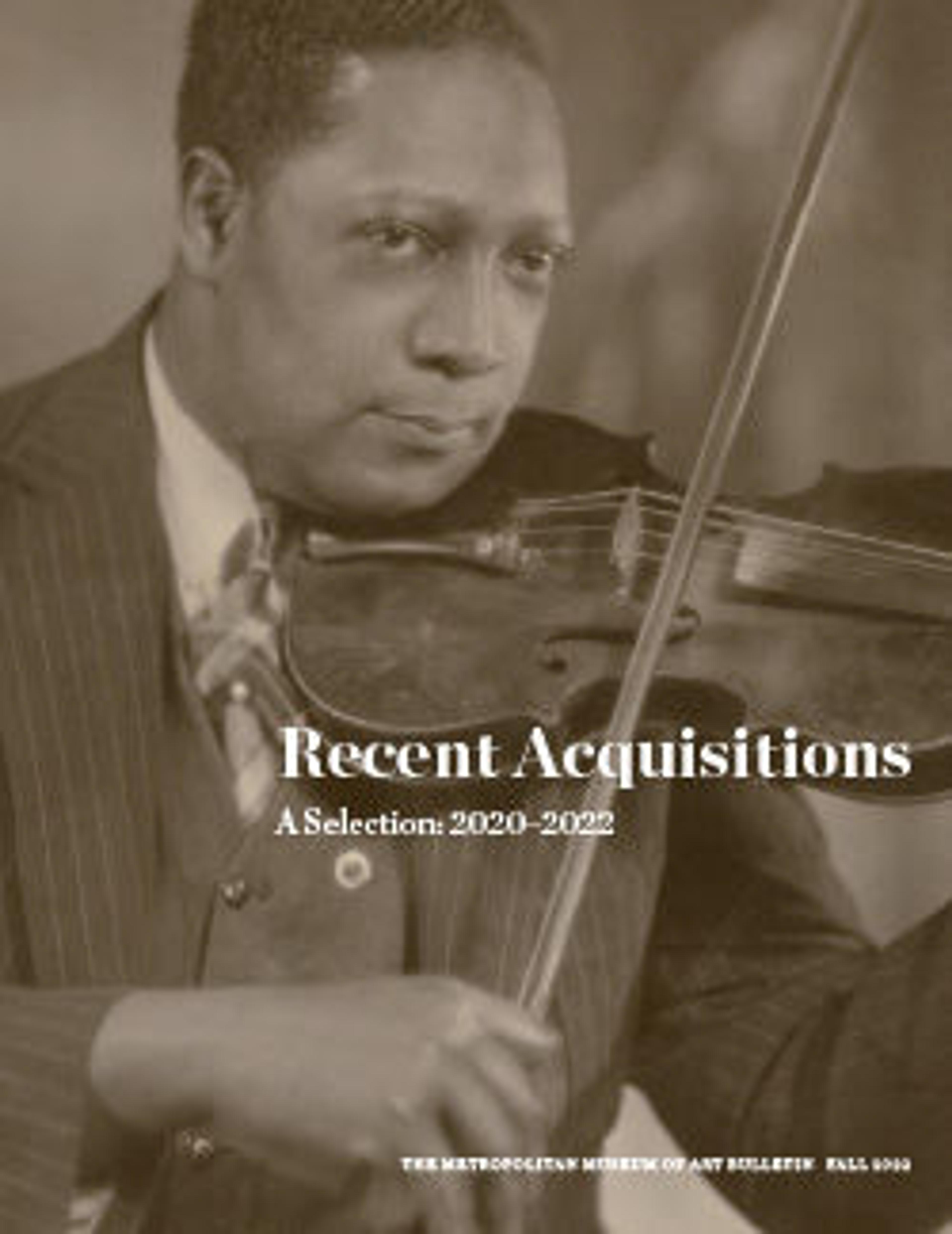

Bust-Length Study of a Man

Despite the nuanced depiction of the man’s head and face, this painting was intended not as a portrait but as a study of a model. Biard focused on the sitter’s features and expression, producing a compelling likeness. Unfortunately, we do not know the name of the sitter, who posed in the artist’s studio in Paris in 1848. In that year, slavery was abolished definitively in France’s overseas colonies, and Biard received a commission commemorating the event. This study likely relates to that picture (Château de Versailles).

Artwork Details

- Title: Bust-Length Study of a Man

- Artist: François-Auguste Biard (French, Lyons 1799–1882 Fontainebleau)

- Date: 1848

- Medium: Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

- Dimensions: 20 1/16 × 18 1/2 in. (51 × 47 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Wolfe Fund and Wheelock Whitney III Gift, 2022

- Object Number: 2022.22

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.