Handscroll of Ten Homoerotic (Nanshoku) Scenes

Miyagawa Chōshun 宮川長春 Japanese

Not on view

Although during the Edo period there was no taboo or stigma associated with male-male sexual liaisons, and many famous writers, artists and other celebrities were known to have same-sex lovers, there are very few surviving deluxe paintings capturing such scenes as found in this handscroll (figs. 1a–j). Erotica known as shunga, “spring pictures,” in the Japanese tradition was often presented in deluxe handscrolls as here, or in printed form, and was produced in great quantities through early modern times. Often a few scenes of male-male sex were integrated into handscrolls, albums or illustrated books devoted to erotica; to have an entire work dedicated to homoerotic liaisons, however, is rare.

By definition, artists of the Ukiyo-e school portrayed images of courtesans or recognizable Kabuki actors. Nearly all of Chōshun’s surviving paintings—he did not design woodblock prints—capture images of beautiful women. This handscroll of male coupling is doubly remarkable. One of the few known paintings by Chōshun depicting a male figure is a hanging scroll of a wakashu (male youth), from the collection of the Tokyo National Museum (fig. 2). That iconic depiction overlaps in details with several of the figures of young men depicted here, notably, the young men’s distinctive hairstyle: forelocks and a shaven pate beneath an extra-long topknot. The wakashu in the Tokyo painting also sports an elegant haori, or thigh-length jacket, trousers, and swords tucked into his sash—attire also seen in the standing figure in the last scene of this handscroll.

All ten scenes of this handscroll by convention depict scenes of lovemaking between an older man and one or a pair of younger men dressed or partly dressed in flamboyant costumes. Some appear to be scions of samurai families (who wield swords), others—wearing brightly colored kimonos more appropriate for young women—are young Kabuki actors who played female roles on the stage, still others were wakashu escorts for older men who frequented the pleasure quarters. One scene includes a female voyeur peeking at the amorous activities from behind a screen. The final five scenes are more explicit than the preceding five, and several show the lovers posed with accoutrements such as a shamisen (three-stringed musical instrument), and a tray of smoking utensils. As was the case of heterosexual erotica of the Edo period, there is often a dimension of playfulness—or sarcasm—to representation of lovemaking, keeping in mind that another term for pornography of the Edo period was warai-e, or “pictures to laugh about.”

Despite the nonchalant societal acceptance of male-male coupling as a completely natural behavior by men at the time, painted images of same-sex erotic encounters are quite rare, though we can be sure that part of the issue is that in modern times many have been destroyed. Images of lesbian sex from the Edo period seem not to survive. The works of male erotica that do survive, as here, mostly date to the early eighteenth century and show scenes of a mature patron who is the active partner with the youth in the passive role. Oral sex is rarely depicted, and kissing infrequent, though this scroll unusually has two instances. These conventions hold true for later woodblock-printed male-sex manuals such as Male Love: Actors Without their Make-Up (Nanshoku hana no sugao) from the later eighteenth century, where again “... the older man invariably [takes] the active role in all sexual encounters and the younger man the passive role." (Timothy Clark, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, London, British Museum, 2013, pp. 20–21 and 443).

Most erotica by Ukiyo-e school artists is created anonymously or signed with a nom de plume, so it is unusual in this case to find the handscroll signed by the artist. But rather than using his usual surname Miyagawa (taken from the name of his birthplace), the artist styles himself Hishikawa Chōshun, indicating that he saw himself as the stylistic heir of the pioneering Ukiyo-e artist Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694), even though Chōshun was too young to have actually studied with him. Indeed, in this work we see the late Moronobu style integrated into the softer, more voluptuous mood of the early eighteenth century, of which Chōshun was an proponent. This early work from Chōshun’s corpus, with brilliantly detailed kimono, also attests to his reputation as one of the great colorists of the Ukiyo-e tradition.

Each of the scenes of male-male lovemaking is a bit salacious, some more than others, and conveys various emotional states of mind:

Scene 1

The opening scene shows a recumbent wakashu (male youth), a sword tucked into his sash, gently pressing against an older man who leans on a decorated lacquer armrest. The young man affectionately grasps the wrist of his mature companion.

Scene 2

A young man in a gorgeous green robe with oversize floral motif seems taken aback by the advances of an older townsman. On the right a wakashu entertainer strums a shamisen (the three-string instrument popular in Kabuki and among male and female entertainers of the pleasure quarters), seemingly oblivious of the mischief taking place nearby.

Scene 3

A wakashu plucks the whiskers of an older patron as he sleeps. The pale brown robes perhaps indicate he is a Buddhist monk since, monks were known to hide their shaven heads by wearing maruzukin, or rounded cloth caps, worn by doctors or elderly men, when they visited the pleasure quarters. A boy attendant with a smoking set in front of him looks on.

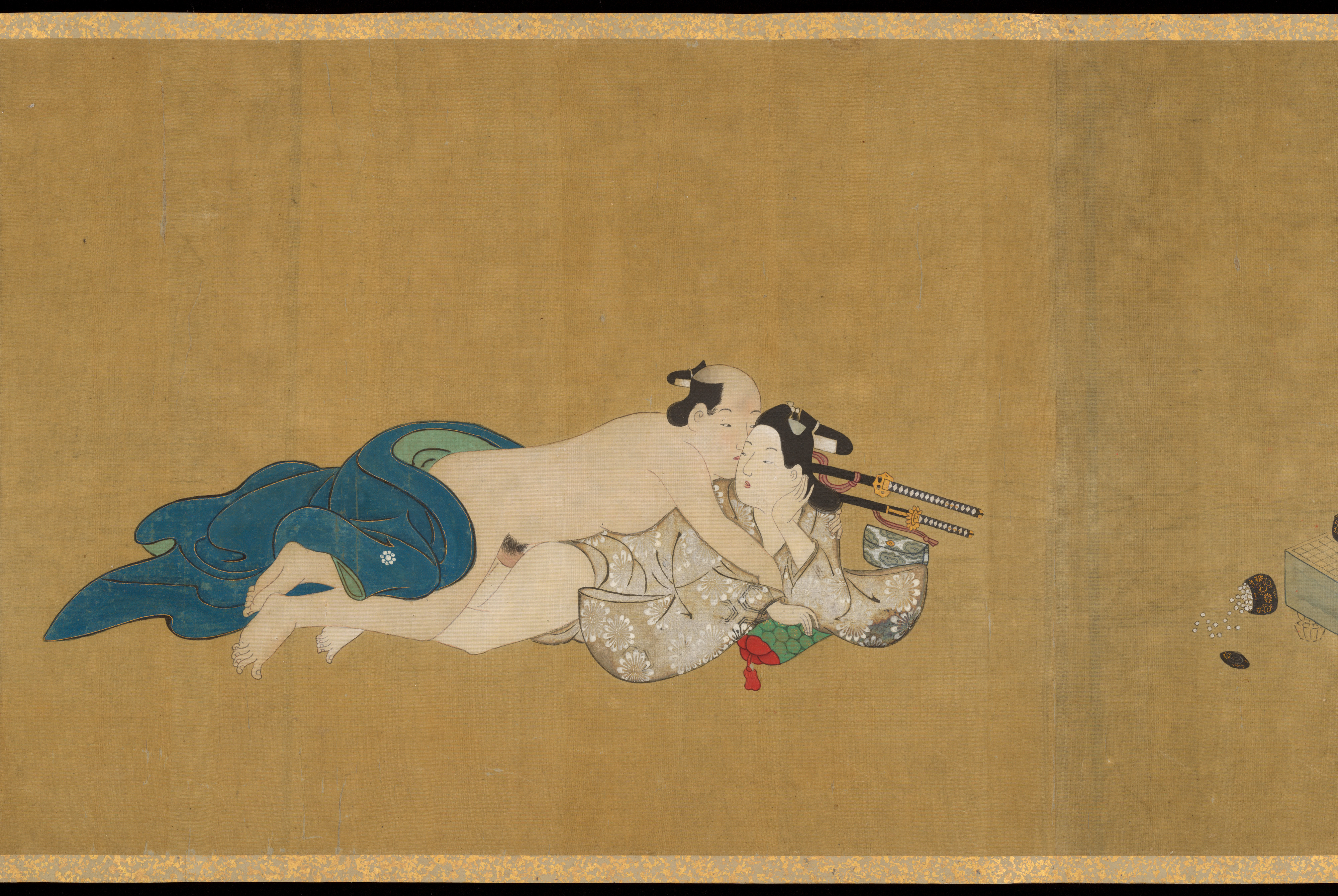

Scene 4

A young man kisses his older patron, scattering the game pieces of an interrupted game of go. This scene is unusual in that the amorous advance is being made by the wakashu.

Scene 5

As the older patron penetrates him from behind, the wakashu seems bored or exasperated by the entire enterprise.

Scene 6

A young man, still in his fundoshi loincloth mounts the older man. They frolic atop a rolled-up yogi¸ referring to the large quilted kimono used as bedding.

Scene 7

A threesome of nearly completely naked men is seated beside a desk with a calligraphy set and a sheaf of paper. The young man with the red fundoshi sits on the lap of the older man, while the other young man embraces the older man from behind.

Scene 8

In contrast to the design of the exultant phoenix embroidered on the yogi quilt, the two lovers, one older, the other much younger, seem almost bored by their frolicking, as the older man tries to penetrate from behind.

Scene 9

An older woman peers at the male lovers from behind a folding screen painted with ink bamboo. They kiss as the older man with a red fundoshi penetrates the young man, still garbed in a green robe decorated with chrysanthemums, a motif associated with the Chinese legend of the Chrysanthemum Boy, the youthful paramour of an emperor. The screen is signed by the artist, “Hishikawa Chōshun hitsu” (painted by Hishikawa Chōshun), borrowing the family name and indicating his indebtedness to Hishikawa Moronobu, the pioneering painter and printmaker of the Ukiyo-e school.

Scene 10.

This final scene shows an older samurai and his wakashu companion in flagrante delicto being interrupted by another, fully dressed young man who has a sword tucked into his sash. The yogi, or oversize quiltlike garment that covers them, is gorgeously decorated with motifs of chrysanthemum flowers and tie-dyed leaves.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.