Longcase clock with calendar and alarm

Movement by Ahasuerus II Fromanteel British

Not on view

While the Fromanteel family was instrumental to introducing the pendulum clock into England, other English clockmakers subsequently made improvements. These improvements culminated in the widespread adoption of the seconds-beating or long pendulum with an anchor escapement, a much more accurate timekeeper than the earlier short pendulum with verge escapement. Whether the inventor was William Clement (1633–1704), Robert Hooke (1635–1703), or, most probably, Joseph Knibb (1640–1711), the development took shape in England after 1670. Within about five years, English clockmakers working in the Netherlands began making longcase clocks that incorporated the improved pendulum. One of the first of these expatriate clockmakers, Joseph Norris (1649/50–after 1696), probably settled in Amsterdam about 1675. As early as 1680, he was making weight-driven movements with long pendulums, which were housed in tall wooden cases. Some of his clocks had crests of carved acanthus leaves and freestanding baroque columns that flanked the doors to their almost, but not quite, English dials.[1] The identity of the Dutch cabinetmaker is not known, but similar cases contain movements by another English expatriate, Ahasuerus II Fromanteel (1640–1703), as well as the Dutchmen Steven Huygens (ca. 1653–1720) and Pieter Klock (1665– 1754).[2] These clocks constitute a remarkable group of some of the earliest longcase clocks made in the Netherlands.

The tall, narrow trunk of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock has a rectangular plinth and a double-skirted base. The trunk is made of walnut veneer, and the door is veneered with rosewood framed by walnut veneers and half-round moldings of walnut. The trunk is punctuated by an oval glass lenticule within a carved and gilded limewood frame. The plinth is similarly veneered with rosewood and walnut on the front and walnut on the sides. The hood is supported on three sides by concave moldings and framed by freestanding baroque columns with Corinthian capitals that flank the hinged glass door for the dial. The panel at the top of the door is carved in relief with ribbons caught up at each end and in the middle, as well as ornamented with bunches of fruit and flowers. The sides of the hood are fitted with carved openwork panels of acanthus backed by modern fabric. Quarter-round baroque columns attached at the back complete the housing for the movement. Above, the architrave is ornamented on three sides with stylized acanthus scrolls, which are carved in high relief and capped by a crest of plump acanthus leaves of carved and pierced limewood. Two gilded wooden eagles perch upon the front corners.

The square dial is made of gilded brass with a silvered chapter ring for the hours divided to show hours, half hours, quarter hours, and minutes. A smaller chapter ring records seconds (5–60, by fives) at the twelve o’clock position. Three apertures at the six o’clock position show the day of the month, the day of the week (in English), and the planetary sign governing the day. The signature and place appear on either side of roman numeral VI. The center of the dial is chased with a design of tulips, and cast heads of winged putti in foliage are attached to the four spandrels.

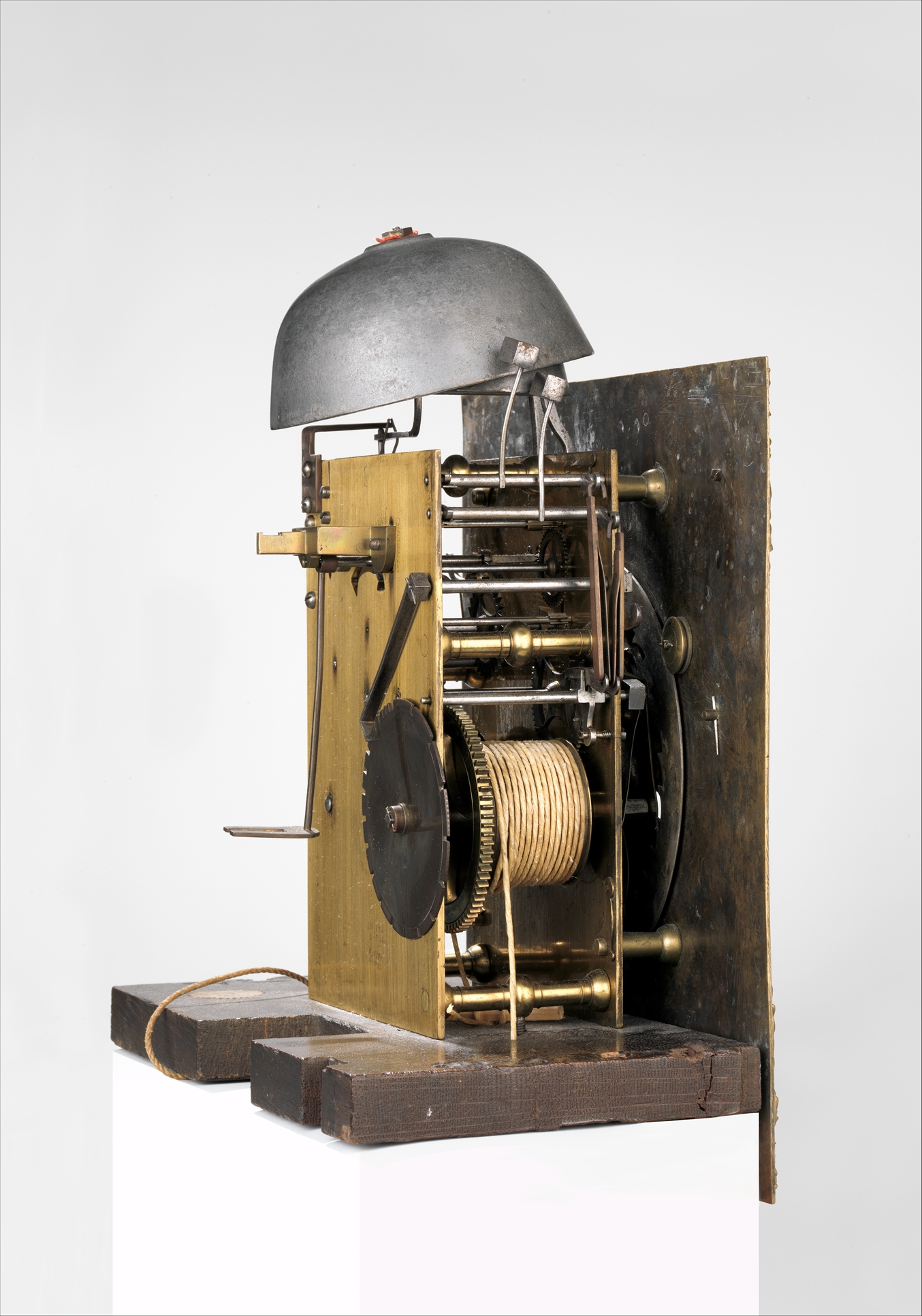

The eight-day, weight-driven movement has count-wheel striking and bolt-and-shutter maintaining power. The movement consists of two rectangular brass plates held apart by five turned pillars. It contains a going train of four wheels that are regulated by a seconds-beating pendulum (about forty inches in length), which is threaded for an adjustable nut at the end, and an anchor escapement. There is an anchor-shaped slot in the back plate that allows easy removal of the anchor assembly. The striking train activates hammers for two nested bells, the lower-toned bell for the hour and the higher-toned one for the half hour anticipating the next hour (known as Dutch striking). The alarm assembly is screwed to the back plate at the roman numeral I position, and it has its own set of two weights of unequal size. The plates are latched to the pillars throughout, and the dial plate is also latched.

While much of the construction reflects Fromanteel’s English training, there are certain elements of the movement that are typically Dutch: the means of attachment of the hammers in the striking train and the sequence of their blows at the half hours, for example, as well as the layout of the calendar on the dial and the tulip pattern engraved in the center. The spandrel ornaments on the dial, on the other hand, may have been imported from London.

The history of the Fromanteel family of clockmakers remains a subject of contention, but Ahasuerus II Fromanteel, the second son of Ahasuerus I Fromanteel (1607–1693), was undoubtedly born in 1640 in London, where he apprenticed as a clockmaker. He moved to The Hague sometime between 1677 and 1681, as he is mentioned as being there at various times between 1677 and 1684. He became a burgher in 1683.[3] Alternatively, he is thought to have established a business in Amsterdam in 1681 with his brother John Fromanteel (1638–1692) in the Vijgendam, now part of the Dam Square near the Rokin.[4] The next record finds him in Amsterdam in 1693, and in the following year, his daughter, Anne, married the expatriate English clockmaker Christopher Clarke (1668–1734). Together, they operated in Amsterdam as Fromanteel and Clarke until Fromanteel’s death in 1703, but Clarke apparently retained the double name until 1722.[5]

Most of the history of the Fromanteels in the Netherlands was not known in early twentieth-century England with the result that someone decided the original signature on the dial of the Museum’s clock, “Fromanteel / Amsterdam,” should read “Fromanteel / London.” The new place-name and faint traces of the original “A” and “m” for Amsterdam can still be found on the chapter ring, and the depth of the newer engraving is noticeably shallower than that of the clockmaker’s name.

The business letterhead of Percy Webster (ca. 1862–1938) at 24 Great Portland Street, London, who identified himself as “Clock-Maker and Dealer in Diamonds, Antique Plate, and Bric-a-Brac,” is still attached to the inside of the door to the trunk of the clock, which provides fairly certain evidence of who changed the signatures. Webster’s obituary in the Times further noted that “If anything ancient, like a skull watch or a Gothic clock came into Great Portland Street with a part missing or ignorantly misplaced, then the business could wait as far as Webster was concerned. He had to retire to his home workshop until that part had been replaced in the proper manner. He was a craftsman first and a dealer a long way after.”[6] Such self-assurance had its consequences, regrettably, as the clock was bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum as English, and the distinctly Dutch features remained a puzzle for more than forty years. It is not known where or when Percy Webster acquired the clock.

Parts of the crest are now missing, and others have been reattached. Some missing veneer has been replaced with mahogany. It is no longer possible to determine whether the case originally had the bun feet that are found on most of the other cases in this group of clocks.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Leopold 1989, pp. 160–61, 165, n. 25; Zeeman 1996, pp. 11, 472–73.

[2] For examples, see Zeeman 1996, pp. 12, 20–31, 35–37, 50.

[3] Leopold 1989, p. 160.

[4] Zeeman 1996, p. 465; Vehmeyer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 965–66.

[5] Leopold 1989, p. 160; Zeeman 1996, p. 462.

[6] “Percy Webster” 1938.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.